Al Franken's Senate Memoir Has Buttload Of Gravitas

How's that for Gravitas?

Several reviews of Al Franken's new book, the humbly-titled Al Franken: Giant of the Senate, have said Al Franken has given himself permission to be funny again, now that he's proven himself to be a serious, hard-working senator. And that's true enough, at least in that this book is Franken's public return to publishing stuff that makes you laugh, but if you were on Franken's fundraising email list, you already knew he was happily keeping a hand in funny-making there, like his 2012 email announcing he'd been endorsed by people in stock photos.

Hello, I’m Woman Picking Out Fruit In Supermarket. And I’m writing to you today on behalf of Al Franken—a Senator who stands up for real people (including those of us who make a living posing for stock photos).

You’ve seen us shaking hands in business suits, posing together on college campuses, and laughing while we eat salads. You’ve seen us on billboards, in magazines, and on pretty much every political website. We are the people in stock photos.

And so on. He also couldn't help but bring out the deadpan when questioning rightwing witnesses during hearings, as when he went after a flack from the Hudson Institute on the matter of whether people were going bankrupt in Europe because of high healthcare costs:

So sure, Al Franken is funny again. As he has been all along, though he's muting it less now. That tension between his ingrained comedic impulses and the need to be a serious public servant is a constant source of tension in Giant of the Senate, and of course opposition researchers' discovery that Franken had written a piece about sex with robots for Playboy (and once, at a 2-AM rewrite session for "Saturday Night Live," pitched a joke involving Andy Rooney confessing to rape -- never intended for actual use, but as an example of the sort of weird turn the sketch might take) almost sank his 2008 campaign, because, as he realized, you can't really litigate comedy. Needless to say, there's a chapter titled "I Attempt to Litigate Comedy."

Franken apologized and swallowed his impulse to argue about the details -- and then returns to them in this book, where he can air them at greater length and make it clear he's not really a robot-sexing rapist, not that he ever was. His story of how that apology was written, with drafts of an apology being emailed between his team, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, and Franken, makes for a fascinating look inside a campaign managing its first major crisis. Franken's still no fan of then-incumbent Norm Coleman, and in a footnote, reassures the reader that after Franken beat him by the narrowest margin in any Senate election, Coleman "landed on his feet and continues to serve the people of Minnesota as a paid lobbyist for the government of Saudi Arabia."

As it turned out, before the Playboy and SNL jokes emerged, one of the jokes Franken's team had worried might be capitalized on by Republicans actually helped win over Harry Reid, who was unsure Franken was Senate material. What really won Reid over was internal polling showing Franken had a chance of beating Coleman, but the meeting with Reid and Chuck Schumer also mentioned a polling question about Franken's "questionable" humor. Reid wanted to know more:

“It says here, ‘Franken made jokes about the Holocaust.’ What does that mean?”

Diane handed our poll to Harry and pointed to the joke we had tested: “I think a bad Hanukkah gift for Anne Frank would have been a drum set.”

Harry Reid started shaking with laughter, and Franken got DSCC funding.

Franken's love for his two careers, comedy and politics, comes through on every page, especially in his discussion of his friendship with Paul Wellstone, whose seat Franken now holds. Wellstone's simple distillation of progressivism -- "We all do better when we all do better" -- motivates Franken's own approach to lawmaking, and is a running theme in the memoir. Injustice really pisses Franken off, something he learned while watching the evening news with his parents every night:

Civil rights, our parents taught us, are about basic justice. And when the news would be full of southern sheriffs turning firehoses, dogs, and nightsticks on demonstrators, my dad would point to the TV and he’d say in his gravelly New York voice, “No Jew can be for that!”

The single best chapter of Franken's 2004 book, Lies: And the Lying Liars Who Tell Them was its chapter on how rightwing media -- and Norm Coleman's 2002 campaign -- lied about and exploited the public memorial service for Wellstone, his wife and daughter, and three staffers, who all died in a plane crash just before the election. Franken doesn't rehash it all here (instead, in a footnote, he urges readers who haven't read Lies to go to a bookstore and read that chapter -- "Tell ’em Al sent you, and that I said it would be fine"), but he's clearly still angry about it. As he should be, because, damn it, it was unfair to Wellstone and to everyone who loved him.

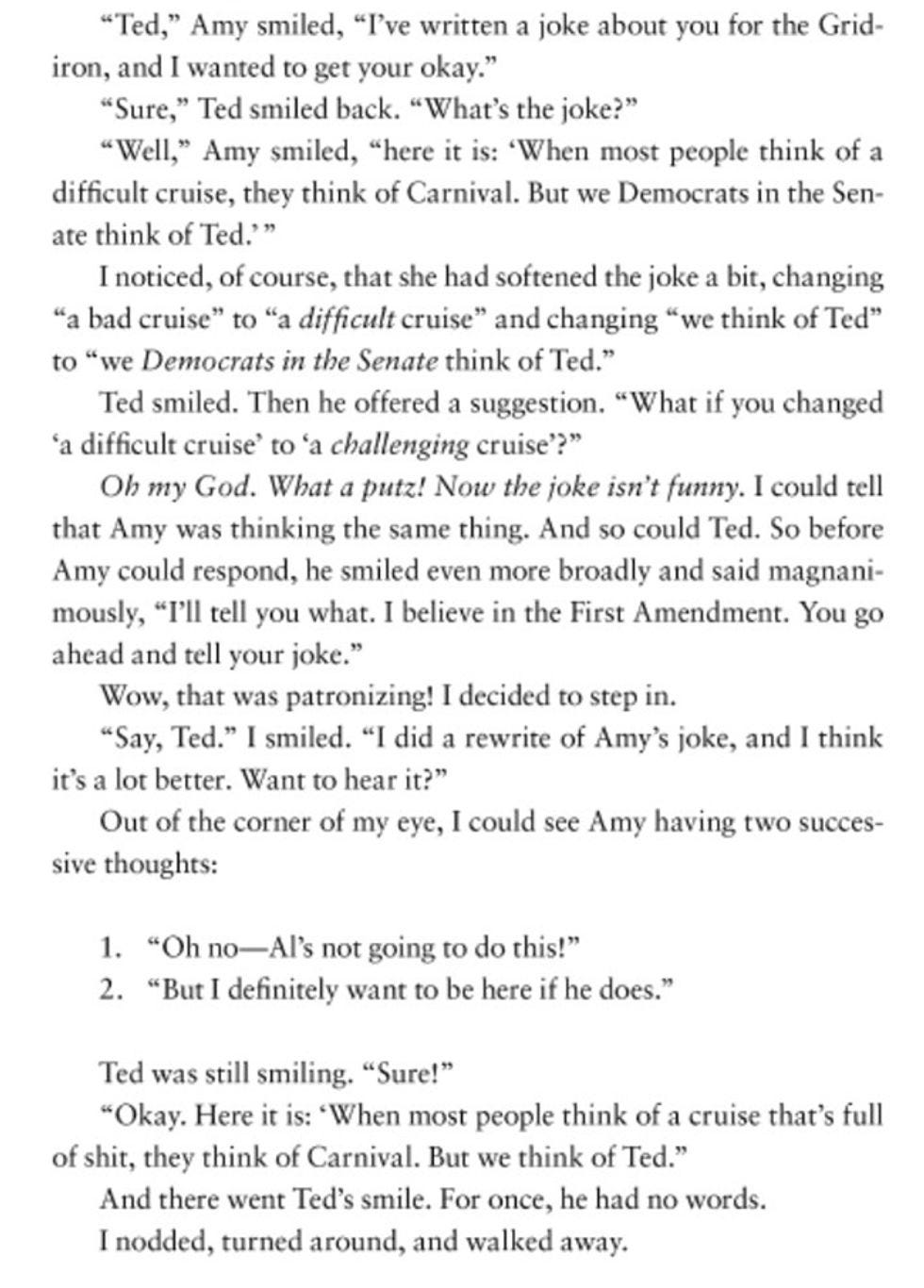

Franken has this weird obsession with truth and fairness, which is why, if this book has an equivalent to the Wellstone chapter in Lies, it's Franken's chapter on Ted Cruz, who Franken readily acknowledges nobody in the Senate likes, not even Republicans:

Anyway, here’s the thing you have to understand about Ted Cruz. I like Ted Cruz more than most of my other colleagues like Ted Cruz. And I hate Ted Cruz.

And why do people dislike Ted Cruz? Because he's smarmy and selfish and backbiting and mean. Because he lies. Because -- this is a big one for Franken -- he takes quotes badly, badly out of context, like claiming a 1997 DOJ report said the Assault Weapons Ban had failed, when in fact the study noted a decrease in murders but cautioned the study didn't cover a long enough period to draw a definite conclusion. And then Cruz went on to lecture Dianne Feinstein -- who'd found the body of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone after he and Supervisor Harvey Milk were assassinated -- about the inviolability of the Second Amendment, his condescension prompting her to reply, "I’m not a sixth grader. Senator." Cruz pressed the point, asking if it would be OK to exclude certain books from protection by the First Amendment.

Franken can now share with us the joke he didn't make in that hearing:

“Well,” I chimed in, “I’ve got a book that I don’t think the First Amendment would permit. It’s called Ted Cruz Is a Pedophile. That would be libel. Unless, of course, you are a pedophile. Which we don’t know.”

No, I didn’t say that. But, man, I wanted to. And I kind of wish I had.

The problem with Cruz, says Franken, is that he's a liar and a jerk, the sort of guy who'd happily shut down the entire government to end Obamacare and insist it was Barack Obama's fault for failing to end Obamacare first. The real problem with Ted Cruz

is simply that he is an absolutely toxic coworker. He’s the guy in your office who snitches to corporate about your March Madness pool and microwaves fish in the office kitchen. He is the Dwight Schrute of the Senate.

There's also this joke about Cruz that made it to Twitter a week before the book came out:

So, yeah, Al Franken doesn't like Ted Cruz, although he likes plenty of other Republicans, "because none of them are sociopaths." The Cruz chapter is here as a counterpoint to the larger point Franken keeps coming back to: the Senate is a small place, and for it to work, people who don't agree with each other on most things have to find places where they can agree. But Ted Cruz doesn't play well with anyone:

Even if you like what he stands for, the most he’ll ever be able to accomplish is being an obnoxious wrench in the gears of government.

Giant of the Senate takes us up to around the time of Donald Trump's inauguration, which for Franken marks a true low point in politics, the culmination of the Lie Machine he's been trying to warn about since his first political book, Rush Limbaugh is a Big Fat Idiot. Says Franken, "Like Trump, I had no previous experience in elected office. Unlike Trump, I was actually bothered by my lack of experience." Franken saw all this developing, but is nonetheless still astonished that such an obvious lying idiot could win the nomination of a major party, let alone the presidency. Franken's first Senate run was almost sunk by the claim he'd made an insensitive joke about rape; Trump won even after multiple women came forward to say he had groped them. "'Huh,' I thought. 'The world sure has changed since 2008.'”

But more than anything, Franken is worried that simple facts no longer seem to matter, even though he'd written two books warning that lying to an insular audience had become an actual worldview and business model for the political right. He wonders:

What would Trump have had to say for a network to cut off his speech and break in, with the anchor saying, “Good Lord. I’m sorry. We’re just not going to show you any more of this crap."

By the time networks started doing real-time fact-checks, Trump was on his way to a narrow electoral win -- one he had to keep lying about, of course. Nonetheless, Franken remains an optimist that at some point, truth has to come back into vogue, though. He can't see how we can continue very long in a post-fact world:

I really think that if we don’t start caring about whether people tell the truth or not, it’s going to be literally impossible to restore anything approaching a reasonable political discourse. Politicians have always shaded the truth. But if you can say something that is provably false, and no one cares, then you can’t have a real debate about anything [...]

I know I’m sort of farting into the wind on this. But I hope you’ll fart along with me. I’ve always believed that it’s possible to discern true statements from false statements, and that it’s critically important to do so, and that we put our entire democratic experiment in peril when we don’t. It’s a lesson I fear our nation is about to learn the hard way.

Franken sincerely hopes that "national gullibility is a cyclical phenomenon," and that after a few years of Trump, we may find ourselves demanding fact-based politics in an "an era of Neo-Sticklerism. And a glorious era it shall be." He doesn't have a firm prescription for how to get there, but is encouraged by the size and volume of the post-election resistance to Trump. It's likely to suck for quite a while, he says, but we progressives can't give up fighting for the idea that we all do better when we all do better. He thinks we've got a pretty good chance, especially if we insist on being rooted in reality.

Al Franken: Giant of the Senate. 2017, Hachette. $16.88 Hardcover / 14.99 Kindle e-book. (Audible narration, read by Al Franken, $12.99 extra -- fun!)

Yr Wonkette is supported by reader donations. Help us fart into the wind with Al Franken, and click that "Donate" linky!

Program note: Dok took a break and read something nice for a change! Dear Shitferbrains will be back next week.