'Doctor Who' Betrays Fans Who Prefer Their Evil Fascist Mad Scientists In Wheelchairs

We think Russell T. Davies made the right call.

David Tennant has returned as the Doctor for a series of much-anticipated 60th anniversary specials, starting next week. (I’ve seen the first but you’ll have to wait for my review.) It’s been more than a year since Tennant’s surprise appearance at the end of Jodie Whittaker’s last “Doctor Who” episode in 2022, so it was great to see him as the “new” incarnation of the Time Lord in this year’s Children In Need special. However, there was more chatter online about the return of classic villain Davros. He’s still played by actor Julian Bleach, who assumed the role in 2008, but he looks a lot different.

Check it out:

Davros, the creator of the Nazi-like Daleks, has until now been depicted as a severely deformed man with only one functioning arm, a ruined face, and who sees through an eyestalk-bulb in his forehead. He relies on a mobile life support system attached to a wheelchair, which resembles the outer casing of a Dalek.

The new Davros is no less sinister than before but he’s no longer disfigured (in body at least) and can move freely. When I saw the minisode, I assumed this just took place before his accident. However, returning showrunner Russel T. Davies confirmed in the behind-the-scenes “Doctor Who: Unleashed” series that this is how he intends to depict Davros moving forward, and he has a good reason.

“We had long conversations about bringing Davros back because he’s a fantastic character,” Davies said. “Time and society and culture and tastes have moved on, and there’s a problem with Davros … in that he’s a wheelchair user who is evil. And I had problems with that, and a lot of us on the production team had problems with associating disability with evil, and trust me, there’s a very long tradition of this.”

He’s right. There’s a very lengthy entry devoted to the concept on the TV Tropes site. The symbolism is rarely subtle, as “a ‘crippled’ body can be used to represent a ‘crippled’ soul — and indeed, a disabled villain is usually put in contrast to a morally upright and physically ‘perfect’ hero. Whether consciously on the part of the writer or not, this can reinforce cultural ideas of disability making a person inherently inferior or negative, much in the same way the Sissy Villain or Depraved Homosexual associate sexual and gender nonconformity with evil.”

On the CW’s “Flash” series, the supervillain the Thinker’s powers resulted in his steady physical deterioration, until he needed a high-tech chair to move. This was a fate the show’s superheroes avoided, whose powers usually just gave them the ability to look great in tight-fitting outfits.

Predictably, the usual suspects whined about “wokeness” or suggested that the original Davros was a fair representation of the disabled genocidal maniac demographic. It’s true that disabled fans have cosplayed as Davros, but so far there’s never been a disabled Doctor or companion. Even the TARDIS is often an inaccessible design.

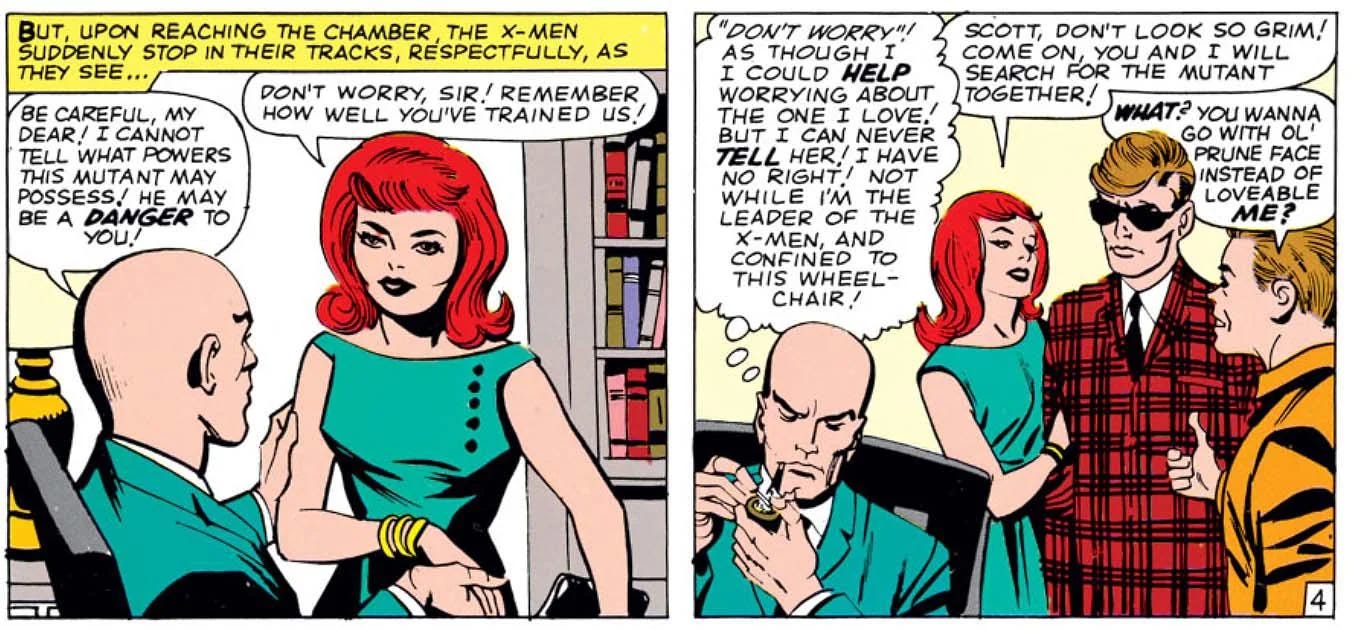

I did see a lot of “what about Professor X?” as if that one heroic example contradicted all the other negative depictions, and Charles Xavier also plays into a related trope. In an early issue from the 1960s, Professor X’s thoughts reveal that he’s in love with the teenage Jean Grey but believes he “had no right” to share his feelings with her because he “was leader of the X-Men and confined to this wheelchair.” The first part makes sense for HR-related reasons, as well as most states’ age of consent laws, but people with disabilities can (and do!) live normal, fulfilling lives. There are more options available than isolation or mad science.

Davros first appeared in the 1975 story “Genesis of the Daleks” and while fans trapped in their own nostalgia might insist that Davros’s physical disability is what makes him a compelling villain, I think this often-referenced scene between him and Tom Baker’s Doctor stands out because of its intense dialogue and how original Davros actor Michael Wisher conveys the Dalek creator’s twisted philosophy.

Wisher wasn’t a disabled actor for whom the role was specifically created. No disabled actor has ever played Davros, which would argue that a physical disability is not so critical to the character that actual personal experience is considered important for the performance.

“I’m not blaming people in the past for this at all,” Davies said, “but the world changes and when the world changes ‘Doctor Who’ has to change, as well. So we made the choice to bring back Davros without the facial scarring and without the wheelchair … I say this is how we see Davros now. This is what he looks like. This is 2023. This is our lens. This is our eye. Things used to be in black-and-white. They’re not in black-and-white anymore.”

Unfortunately, some fans demand that life remains in black-and-white: “I’ll bet good money that no-one before today considered one of the most iconic villains in #DoctorWho history to be problematic because he was in a 'wheelchair',” insisted someone who should never gamble or enter into demonic contracts. “It's an iconic character design, and to dispose of it now is a ridiculous decision.”

Record producer and songwriter Ian Levine whined, “Russell T. Davies has now caused the most massive backlash against him. All his former supporters, like me, have now turned against him. He went one step too far.”

If someone doesn’t find the original Davros offensive or aren’t interested in understanding why other people might, that’s their right. However, why complain about change in a series defined by change? I think we know why, of course, and regardless of how he looks now, Davros would likely approve of their contempt for anything that doesn’t fit into their narrow world view.

Follow Stephen Robinson on Bluesky and Threads.

Subscribe to his YouTube channel for more fun content.

Catch SER on his podcast, The Play Typer Guy.

My sister was a poor widowed 50 year old wearing a Dr. Who shirt at her grocery store cashier job when a handsome Scottish physicist said, "I like your shirt." Paul the Physicist is now my favorite family member.

Thanks for this, SER.

I know I can always count on your to understand this stuff.