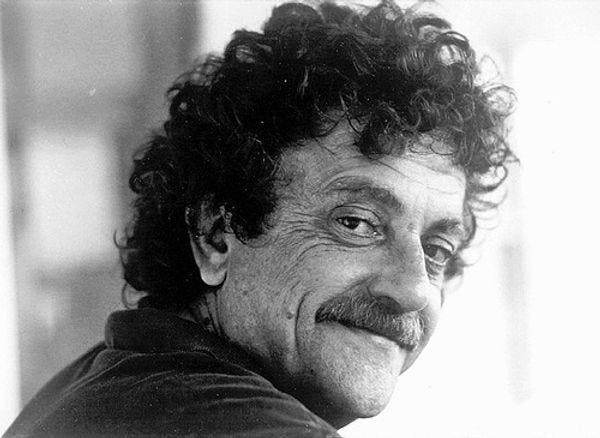

Fine Here Is Your Bloody Kurt Vonnegut For The Armistice. Pray For Peace.

Peace is impossible, so we'll settle for a traditional wish for peace.

It is November 11, 2019, and time again for our annual tribute to Kurt Vonnegut, who made us want to be a writer, and to his birthday, which this year falls on the 101st anniversary of the end of what was optimistically called the War to End All Wars. This is our eighth consecutive Kurt Vonnegut's birthday here at Wonkette, if you can believe that!

Of course, it ismandatory we begin properly, with the quote from Breakfast of Champions that we take down from the attic every year, because what's a tradition without the proper decorations?

So this book is a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders as I travel in time back to November eleventh, nineteen hundred and twenty-two.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy [...] all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans' Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans' Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans' Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don't want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

-- Breakfast of Champions (1973)

As we always note, this is simply the most Vonnegut-y thing you could wish for: the time travel, the sentimentality, the affectation (which he used throughout Breakfast and in other novels) of writing out the year, and that beautiful line, "men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind" -- Jesus, that's nice stuff.

Last year, for the centenary of Armistice Day, Britain's Imperial War Museum commissioned a data-driven reenactment of the moment the Armistice took effect. The data was more or less the seismic record of shellfire from "sound ranging" equipment, which used barrels of oil buried in the ground to collect vibrations from enemy guns, to better aim Allied efforts to fire back. Sound engineers took the visual record of the Great War's last moments as a guide to re-creating what it might have sounded like near the American lines on the River Moselle, as the always interesting Open Culture blog explains:

In the "graphic record" of the Armistice, just below, we can "see" the deafening sounds of war and the first three silent seconds of its end, at 11 A.M. November 11th, 1918. The film strip records six seconds of vibration from six different sources, as the graphic, from the Army Corps of Engineers, informs us. "The broken character of the records on the left indicates great artillery activity; the lack of irregularities on the right indicates almost complete cessation of firing."

You might notice a couple little breaks in one line on the right—likely the result of an exuberant "doughboy firing his pistol twice close to one of the recording microphones on the front in celebration of the dawn of peace."

Here's the audio recreation. Not sure the Voice of God was successfully captured:

Listen to the Moment the Guns Fell Silent Ending World War I, River Moselle, American Front youtu.be

And then there's the horrendous stupidity of scheduling a nice, poetically memorable time to end the war, and then fighting like mad right up to that moment. May as well throw away more lives with a meaningless last-minute charge.

Vonnegut was always a bit worried about his own status as a writer of serious literature, having raged both against being dismissed first as "merely" a science fiction writer, and later against being taken seriously by college students and counterculture types, but not by serious adults. Of course, even kvetchy Vonnegut is good Vonnegut:

I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled 'science fiction' … and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.

Weirdly enough, science fiction has often shared that ambivalence : Vonnegut was a finalist for SF's two biggest awards, the Hugo and the Nebula, but never won them, nor has he ever been awarded the field's lifetime achievement award. But we digress, which seems appropriate when talking about Kurt Vonnegut.

And it's not entirely a digression. The Great War, after all, was arguably the world's first science fiction war, a conflict in which advanced technology made a hash of military strategy and tactics, not to mention millions of combatants. It was the last time, thank Crom, that the world ever saw anything as insane as generals insisting on cavalry charges against entrenched troops behind barbed wire, who then used machine guns to cut down row after row of attackers. War included, for the first time, flying machines, nearly impenetrable armored vehicles, the widespread use of poison gas (the first doomsday weapon), and a death toll that wiped out entire generations of the combatant nations' young men. (America came to the fight too late, although we certainly had our own mass casualties, too.) The war gave the world future shock over a half century before Alvin Toffler coined the phrase.

You want bug-eyed monsters on an alien, science-fiction battlefield? Here you go.

'Stormtroops Advancing Under Gas', Otto Dix, 1924

Or a similar science-fictional nightmare, from the English perspective, in Wilfred Owen's "Dulce et Decorum Est" :

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Nationalistic lies battered to nothing by the horrors of technological war: It's not a theme exclusive to science fiction, of course, but it's a central concern, regardless of whether you add lasers, interspecies invasions, or time travel.

And if you'd like to have a nice conversation in the comments about whether Starship Troopers is a big gross bucket of militaristic jingoism or a brilliant satire of militaristic jingoism, please go right ahead. (The Paul Verhoeven movie is definitely taking the satiric piss. The original Robert Heinlein novel? Damned if we can tell.)

As Paul Fussell's The Great War and Modern Memory and Robert Hughes's The Shock of the New both explain, the collision of modern, mechanized warfare and traditional expectations also shaped the development of literature and art for the rest of the century -- again, not just in science fiction, but everywhere. If you've never watched the brilliant PBS adaptation of Hughes's work, some kind art freak has put it up onYouTube.And because the Second War was in some ways a continuation of the first, let us also recommend Fussell's brilliant and disturbing look at the realities of combat in WWII, Doing Battle, in which I learned that one frequent cause of injury in WWII was being hit by a comrade's explosively amputated body parts.

What a species we are!

For all the horror and Forever War in science fiction, there's also the utopian strain in the genre, and getting back to that original Vonnegut quote up top, what could be more utopian, more sense-of-wonder, than a holiday dedicated to commemorating not the war, but the peace? It was a peace achieved not through crushing the foe, but through humans deciding this madness has to end, and it finally arrived, right on schedule, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. Only fitting that Vonnegut, an atheist who thought about God a lot, would find the "voice of God" in a voluntary cessation of fighting.

And yes, we can acknowledge it was a very imperfect peace: The reparations imposed upon Germany set up its economic collapse and paved the way for the rise of Hitler and the second World War. There's no telling how history might have played out differently if the US hadn't gone all America First and opted out of the League of Nations -- might be a nice work of alternative history there.

While other nations involved still celebrate the Armistice, or Remembrance Day, in the USA, the holiday honoring the end of a war lasted only until 1954. A year after the muddled, muddy, unsatisfyingcease-fire in Korea, Congress changed the focus. Instead of a holiday commemorating peace, November 11 became one more day to celebrate the warriors, a substitution Vonnegut first decried in Mother Night .

"Oh, it's just so damn cheap, so damn typical." I said, "This used to be a day in honor of the dead of World War One, but the living couldn't keep their grubby hands off of it, wanted the glory of the dead for themselves. So typical, so typical. Any time anything of real dignity appears in this country, it's torn to shreds and thrown to the mob."

It's a very real loss, and we would do well to remember this holiday started out as a solemn commemoration of a time when humans agreed to say, "Stop. No more"

What would Kurt Vonnegut say about a US president who last year couldn't be bothered to face a little bit of rain while visiting the graves of Americans who died in the Belleau Wood? He'd be nauseated, of course, although we suspect it's not that failure of patriotism that would bother Vonnegut. Kurt Vonnegut was never big on honoring warriors, since that so easily slides into honoring war itself. He'd seen close up, in the scorched alien remains of Dresden, the practical effects of total war. All wars, he reminds us, are fought by children, really. Still, we think he'd be ruefully amused by Trump's avoiding a little rain.

We'd like to believe Vonnegut would instead be heartened, at least a little, by French president Emmanuel Macron's words for the centenary. Macron actually seemed to understand the lessons of Armistice Day:

Macron described himself as a patriot, and said: "Patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism. Nationalism is a betrayal of patriotism. In saying: 'Our interests first, whatever happens to the others,' you erase the most precious thing a nation can have, that which makes it live, that which causes it to be great and that which is most important: its moral values."

He warned: "Old demons are resurfacing. History sometimes threatens to take its tragic course again and compromise our hope of peace. Let us vow to prioritise peace over everything."

He said the traces of the first world war had never been erased from Europe nor the Middle East and called on countries to stand together in "goodwill" against climate change, poverty and inequality. "Let us build our hopes rather than playing our fears against each other."

You want foreboding? Neither Donald Trump nor Vladimir Putin walked with Macron and other world leaders in a procession up the Champs Elysees to the Arc de Triomphe. Instead, they arrived separately, via their own motorcades, as a matter of "security."

It's just so damn cheap, so damn typical. And while Vonnegut called himself "that impossible thing, a pacifist," he surely would have been horrified by Trump's shameful abandonment of the Kurds.

As for Yr Wonkette, we'll stick with Kurt Vonnegut and the hope that human imagination can be turned away from the celebration of slaughter. It would be a far better world if we could, now and again, try to remember the good we're capable of.

Also, a tweet we saw this morning:

Me & @iAmTheWarax: ... Child: Isn’t it sad about WWI? I really hope there isn’t a WWIII. If there is, I really ho… https://t.co/EZ4Gr8eoiW

— Natalia Antonova 😼🕵️♀️ (@Natalia Antonova 😼🕵️♀️) 1573484724.0

Amen.

As ever, we'll close with Eric Bogle's version of "And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda," because music is sacred.

Eric Bogle - The Band Played Waltzing Matilda youtu.be

The last living veteran of that war, Florence Green, died in 2012 just two weeks short of her 111th birthday. Let us dream of a world that no longer manufactures any new veterans.

[ Atlantic / WaPo / Army Times / Medium / CBS News / Guardian / WaPo ]

Book Links, with Wonkette kickbacks!

Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

Kurt Vonnegut, Mother Night

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918

Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory and Doing Battle

Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

Joe Haldeman, The Forever War

Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers

Yr Wonkette is supported entirely by reader donations. You keep supporting us, and we'll keep tinkering with how to remember Kurt Vonnegut.

The War To End All Wars doesn't seem to have worked.

Even reading the lyrics reduces me to tears...