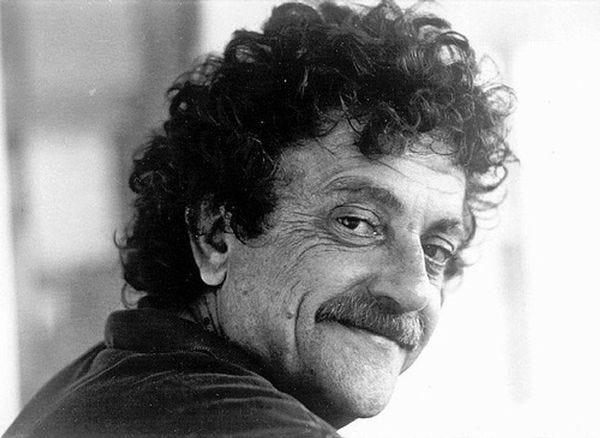

Fine Here Is Your Kurt Vonnegut, On The First Armistice Day Since The Latest War Ended

'Poo-tee-weet?'

It is November 11, 2021, and time again for our annual tribute to Kurt Vonnegut, who made me want to be a writer, and to his birthday, which this year falls on the 103 rd anniversary of the end of what was optimistically called the War to End All Wars. This is our tenth consecutive Kurt Vonnegut's birthday column here at Wonkette, if you can believe that!

As is our tradition, we get our copy of Breakfast of Champions down from our mental shelf, dust it off, and hold it up to the light. It's still the right quote for the occasion:

So this book is a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders as I travel in time back to November eleventh, nineteen hundred and twenty-two.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy [...] all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans' Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans' Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans' Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don't want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

-- Breakfast of Champions (1973)

And as I traditionally note, this is simply the most Vonnegut-y thing you could wish for: the time travel, the sentimentality, the affectation (which he used throughout Breakfast and in other novels) of writing out the year, and that beautiful line, "men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind" — Jesus, that's nice stuff.

This year, we celebrate Kurt Vonnegut's birthday and the end of the first modern war — a science fiction spectacle, as we've noted previously — in something of an odd circumstance. For the first time since I've been doing this, the United States of America is no longer at war in Afghanistan.

We can't quite say the Forever Wars have ended, however, since troops are still being deployed to Iraq, where some 2,500 troops remain. Another 900 troops are still in Syria . US officials said in October that troops will be staying in both countries for the foreseeable future.

Kurt Vonnegut was still alive to rail against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in his final collection of essays, A Man Without A Country , published in paperback in January 2007, three months before he fell, hit his head, and died. So it goes.

Vonnegut's best novel, Slaughterhouse-Five , ends with Billy Pilgrim, his time-traveling protagonist, walking out into the ruins of Dresden with other American soldiers who had been captured, and then survived the firebombing of that city in a deep slaughterhouse basement, just as Vonnegut himself had. Vonnegut did not report hearing the voice of God at the end of his war.

In the novel, the war is over and the German army has disappeared to go fight the Russians, and a bird asks Billy Pilgrim, "Poo-tee-weet?"

Vonnegut sets up this ending in the prefatory first chapter of Slaugh terhouse-Five, explaining to his publisher that what he'd planned to be his big fat war epic had turned out different from how he'd imagined it:

Sam — here's the book.

It is so short and jumbled and jangled, Sam, because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds.

And what do the birds say? All there is to say about a massacre, things like "Poo-tee-weet?"

Needless to say, it's a far better book by not being a fat war epic, because those kinds of books aren't necessarily very honest.

Americans have largely left Afghanistan, although efforts to rescue Afghans who worked with the US continue, mostly carried out by volunteers. As a New Yorker piece published in September noted, many Afghan women in rural areas may even welcome the Taliban for bringing order, compared to the corruption of the local warlords who thrived while the Americans were there. For good or ill, the war there is over, unless a new civil war erupts, always a possibility where there are lots of factions and lots of weapons from all over the world.

The Taliban may be terrible, but the end of the war at least means an end to the raids, by both US and Afghan forces, that killed or maimed countless Afghan civilians. One woman listed all the relatives she's lost since the Americans came:

There was Muhammad, a fifteen-year-old cousin: he was killed by a buzzbuzzak , a drone, while riding his motorcycle through the village with a friend. "That sound was everywhere," Shakira recalled. "When we heard it, the children would start to cry, and I could not console them."

Muhammad Wali, an adult cousin: Villagers were instructed by coalition forces to stay indoors for three days as they conducted an operation, but after the second day drinking water had been depleted and Wali was forced to venture out. He was shot.

Khan Muhammad, a seven-year-old cousin: His family was fleeing a clash by car when it mistakenly neared a coalition position; the car was strafed, killing him.

The list goes on, five more paragraphs, each about one family member lost, and there were many more deaths; sixteen in her family alone. There's nothing much intelligent to say about that, either.

Meanwhile, here at home, a substantial portion of the population thinks America can only be put right by a good civil war, or at least by terrorizing school board members and the folks who run our elections. Vonnegut had an especially low opinion of such bullies, and I can't help but think he would have been absolutely astonished that vast numbers of Americans would refuse to get vaccinated against a disease that has now killed three-quarters of a million of us.

But Uncle Kurt would certainly recognize the people who are calling for dirty, anti-American books to be pulled out of the schools, and perhaps even burned . People who think their mission is moral improvement have been at war with Slaughterhouse-Five since it was published fifty-two years ago. No doubt it will eventually get caught up somewhere in the current enthusiasm for cleansing the schools, although it may be spared in some of the early rounds because it's primarily about the cruelty of war, not about America's internal cruelty to Americans or about gay people.

In 1973, Slaughterhouse-Five wasn't merely removed from library shelves in Drake, North Dakota. The school board ordered a custodian at the high school to burn all 32 classroom copies of the novel — and later, others — in the school's furnace, prompting Vonnegut to write to Charles McCarthy, the chair of the Drake School Board, to remind him that Vonnegut was an American, a veteran, a good citizen who had never been arrested, and a human being. The full text of the letter can be found here; to save space, here's a video of the letter being read by actor Benedict Cumberbatch:

We can't resist copy-pasting at least this paragraph, which is every bit as true nearly forty years later:

If you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind. They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are. It is true that some of the characters speak coarsely. That is because people speak coarsely in real life. Especially soldiers and hardworking men speak coarsely, and even our most sheltered children know that. And we all know, too, that those words really don't damage children much. They didn't damage us when we were young. It was evil deeds and lying that hurt us.

Vonnegut did not receive a reply.

But like his spiritual forbears Mark Twain and George Orwell, Vonnegut definitely did know that people could be better, or he believed it strongly enough to keep from despair, if we would just remember that other people are indeed people.

In 1965's God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, his sixth novel, the main character offers this benediction to newborn twins:

Hello babies. Welcome to Earth. It's hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It's round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you've got a hundred years here. There's only one rule that I know of, babies-"God damn it, you've got to be kind."

Vonnegut was still chewing on the very same idea in his final novel, Timequake (1997):

Many people need desperately to receive this message: 'I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.'

He might well be cheered to see that in California agriculture country, farmworkers and growers and activists and health care clinics have all worked together to get well over 90 percent of their communities vaccinated against our latest plague. He'd be heartened that there's a fighting chance that we'll finally take serious action on climate, and on expanding the care economy. He'd remind us that the loudmouths are just that, and that we can do better, because we have done better at times.

The last living veteran of the Great War, Florence Green, died in 2012 just two weeks short of her 111th birthday. Let us dream of a world that no longer manufactures any new veterans.

As ever, we'll close with Eric Bogle's version of "And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda," because music is sacred.

And now it is your OPEN THREAD.

Yr Wonkette is supported entirely by reader donations. You keep supporting us, and we'll keep tinkering with how to remember Kurt Vonnegut.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

You Probably Need Books!

Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut, A Man Without a Country

Kurt Vonnegut, Slapstick ,

Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater,

Kurt Vonnegut, Timequake

Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918

Ginger Strand, The Brothers Vonnegut

In the letter, he says there are no copies of the letter.

Bad for him, you mean, right? That would indicate there is some karma at work at last.