May 29 In Labor History: Rosie The Riveter Eats Her Own Goddamn Sammich

But who will make the sandwiches if the women are in the workforce?

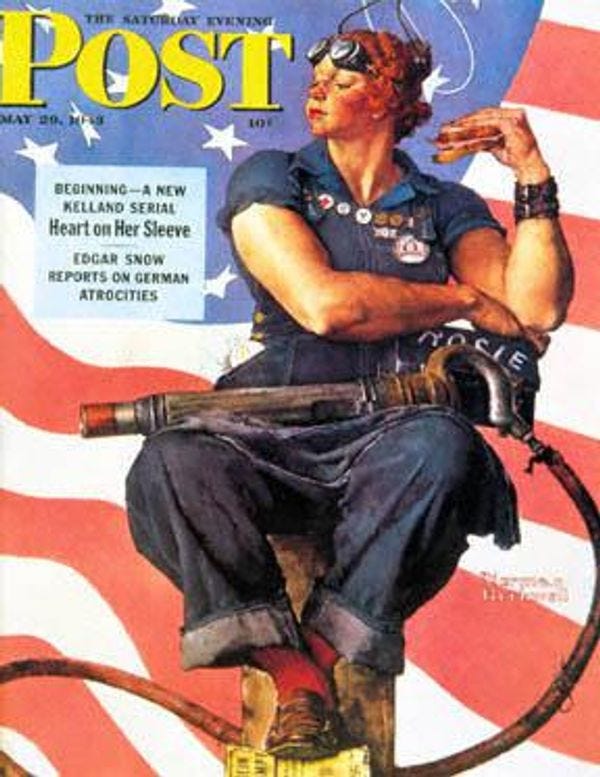

On May 29, 1943, Norman Rockwell published a Saturday Evening Post cover of a woman working an industrial job. This cover represented the millions of women entering the workforce during World War II to build the material needed to defeat the Axis. This image was part of a larger cultural phenomena referring to these women workers as Rosie the Riveter.

When the United States entered World War II in late 1941, it created an instant labor shortage. With immigration not a possibility except from Mexico, it opened up unprecedented economic opportunities for both women and minorities. The number of women working increased from 12 to 20 million. Before the war, most working women labored in poorly paid service jobs, clerical work, or sales positions. When they did work in manufacturing, it was often in the ever-exploitative apparel industry, mostly in the South and still a bit in New England. During the war, their labor became much more valuable. The number of women in manufacturing grew by 141 percent and the number in industries making material for war skyrocketed by 463 percent. Women working in domestic service declined by 20 percent.

Just because women were needed of course didn't mean that employers had any intention of paying them the same as men, a policy unfortunately acceptable to many unions as well. Men working in a defense production factory averaged $54.65 per week with women averaging only $31.50. While women did join the big industrial unions to work in these factories, because of seniority provisions, they were at the bottom, setting them up to be the first fired after the war. Some contracts for women even stipulated that women would only hold the job until the war's conclusion. Still, the wages were vastly higher than before the war and women were able to partake of greater economic benefits than any time in US history.

The majority of women entering the workforce were older. Sixty percent of the women were over the age of 35 and most of them did not have young children. Few employers provided childcare and the government did not recruit these women. One exception to this was at the Kaiser shipyards on the West Coast, which had 24-hour child care and therefore employed a lot more young women.

The term Rosie the Riveter first appeared in a 1942 song that became a hit for Kay Kyser. A woman named Rosalind Walter was the inspiration for the song. Walter was an elite woman who took a job in an aircraft factory before entering philanthropy after the war. The always-influential Rockwell popularized the image even more with his cover. Rockwell based his woman on a phone operator he knew in Arlington, Vermont, named Mary Doyle Keefe, to whom he then apologized for making her look so burly. The image then toured the country as a fundraising drive for war bonds.

The popular image of Rosie the Riveter at the time was associated with a Kentucky woman named Rose Will Monroe who moved to Michigan during World War II and worked as a riveter building bombers in an Ypsilanti factory. Monroe was asked to be in a promotional film about the women workers and received some short-lived fame that way.

We Can Do It

The most famous Rosie image, the "We Can Do It" poster, in fact was not designed for the campaign at all. Westinghouse hired a Pittsburgh graphic designer named J. Howard Miller to design an image of a woman worker for its War Production Coordinating Committee. It is believed Miller based his image on a photo of a woman named Geraldine Hoff, who worked as a metal-stamping machine operator in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was only shown to Westinghouse workers as part of a good morale, corporate-values drive (read, anti-union drive) for two weeks in February 1943 and was then forgotten. In fact, the poster did not become widely associated with Rosie the Riveter until the 1980s.

So to repeat, the image you think of when you think of Rosie the Riveter was an image intended to discourage women from joining unions. The "We" in "We Can Do It" is Westinghouse workers following the leadership of Westinghouse management. Of course, there's certainly nothing wrong with co-opting rightwing materials for our purposes; certainly conservatives do this all time to images and ideas of the Left. Still, it's worth knowing this. Moreover, it's also important to point out how gender-normative the now popular image of Rosie is compared with Rockwell's image. The Rosie that people get tattooed to them is hot in a very traditional way. Given her status as a feminist icon today, it's also worth noting how much the image reinforces normative standards of beauty.

Ladies Keep Your Pants On

The war meant a lot of hard work. But wartime work could mean a lot of fun too, perhaps too much for some. Senator Prentiss Brown (D-MI), member of the Army Ordinance Committee, spoke out about fun getting in the way of war production:

"The pumps were found to be in perfect condition and no reason could found for their failure until a pair of ladies panties were taken from the suction pipe. These were undoubtedly discarded during the construction of the vessel in a moment of thoughtlessness and left lying in the tank, later finding their way into the pipeline…In order that all may cooperate one hundred percent in the war effort and the total destruction of the Axis Powers, it is respectfully requested that lady workers keep their pants on during working hours for the duration."

Many women wanted to continue working after the war (one poll put the number at about 75 percent), but the postwar economy would be nothing if not patriarchal. Nearly all the women working in factories lost their jobs by the end of 1946. Yet despite overwhelming popular support for women staying at home and letting men work in a single-family economy during the 1950s, women soon entered the workforce at rates surpassing that of World War II. In one poll, 86 percent of Americans said that married women should not work if jobs were scarce and a husband could support her. Yet by 1952, two million more women were working than in 1945. But instead of well-paying industrial jobs, they were effectively filling service positions in the booming postwar economy, going back into sales, office work, working as flight attendants , and returning to domestic service. The fight for women to become an accepted part of the industrial workforce would not be fully engaged again until the 1970s .

In 2000, President Bill Clinton created the Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park at the site of a former Kaiser shipyard in Richmond, California, giving the National Park Service a site to interpret this history. I haven't visited unfortunately.

The original Rockwell painting was sold in 2002 for $4.9 million and now resides in the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Why This Is Important Today

Duh, it's Rosie! But seriously, women are still not considered as central to the industrial workforce as they should be. It's not just that Rosie the Riveter is a World War II icon. She also should be a representation of an entire history of women in industrial work. Women continue to make up core parts of the industrial workforce today. It's just that those women labor and die making our clothing in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Cambodia, India, China, etc. Throw in the effect of the pandemic on women's employment, which by some measures is back to numbers last seen in the 1980s, and you see the erasure of decades of gains.

Further Reading

Maureen Honey, Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II

Kathleen Endres, Rosie the Rubber Worker: Women Workers in Akron's Rubber Factories during World War II

Julia Brock, Jennifer W. Dickey. Richard Harker and Catherine Lewis, eds., Beyond Rosie: A Documentary History of Women and World War II.

Keep Wonkette on the line, please, if you are able!

I bet it was Kilroy (who was there) getting into Rosie's pants.

Remember, after the Boomers the Beat was born.