Ron DeSantis Can’t Make Us Forget Catherine Burks-Brooks Or The Forces She Fought

Rest in power.

“I tell everybody, I kick my way in.”

Those are the eternal fighting words of civil rights activist Catherine Burks–Brooks, who died last week at 83. She lived that long while never submitting to a racist society.

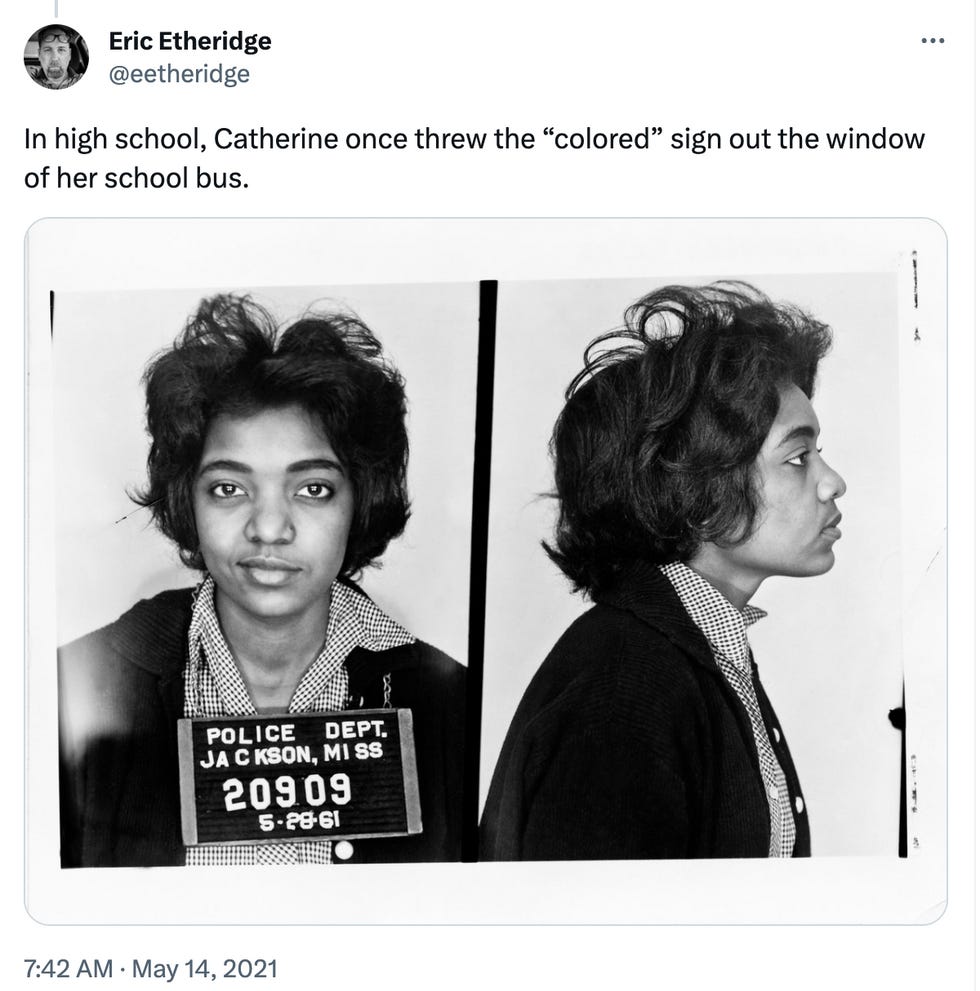

Growing up in Jim Crow Alabama, she wouldn’t move out of the way on the sidewalk when white people crossed her path — breaking the law but not her spirit. In high school in the 1950s, she threw the "colored sign" out the window of her school bus. Once, when a white man in Nashville threatened to stamp out a cigarette in her face, demonstrating his strength through moral weakness, she sang to herself “We Shall Not Be Moved.”

Catherine Burks-Brooks was a bad ass, and if you're hearing about her for the first time, that's probably deliberate. As Chuck D said, most of my heroes don't appear on no stamps, and she's one of them.

Twitter

Catherine Burks-Brooks was a 21-year-old college student when she joined the Freedom Rides with the late John Lewis. On May 4, 1961, brave souls boarded two buses in Washington, DC, headed for New Orleans. This seemingly banal action bore the weight of revolution: They were challenging America to practice what it preached and actually obey the 1960 Supreme Court ruling that banned segregated facilities for interstate passengers.

This was not a battle that could be won simply by voting harder — not on its own. Activism was required, no matter how upsetting to white moderate sensibilities.

On May 14, about 200 white people attacked the Greyhound bus outside Anniston, Alabama. They shot out the tires and firebombed it. Riders were severely beaten. Racists latter attacked Freedom Riders on the Trailways bus and at the Birmingham bus station. But the Freedom Riders wouldn't relent, refusing to let white violence neutralize the gains they'd won within a legal system already biased against them.

Despite the known dangers, Burks-Brooks volunteered to take the first bus to Birmingham. “After we got word about the beatings in Birmingham and bus burning near Anniston, we decided that we would take up the Freedom Rides,” she said in 2011. “We knew it had to be done and that there was a strong possibility we could get killed. But when you accept that idea, you lose your fear.”

She joined Lewis, Bill Harbour, her future husband Paul Brooks and Jim Zwerg, a white student at Fisk University. Brooks and Zwerg sat together and were immediately arrested at the Birmingham city limits.

Birmingham Police Chief Bull Connor arrested the remaining Freedom Riders for "their own protection." When he got around to releasing them, Connor and his thugs drove these true patriots to the Alabama/Tennessee border and abandoned them in the middle of nowhere.

Lewis recalled how impressed he was with how Burks-Brooks engaged Connor in conversation during the trip.

They talked about the 1948 Democratic convention, where South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond led a walkout to protest the Democratic Party’s civil rights platform. Thurmond and his followers, including Connor, then formed the Dixiecrats, who held their nominating convention at a public building in Birmingham — a waste of tax money, Burks–Brooks said.

She also invited Connor to have breakfast with the students when they got to Nashville.

“I couldn’t let old Bull have the last word,” she said. Referencing one of the cowboy movies she liked, she declared that they “would see him back in Birmingham by high noon!”

“I had no fear of the Bull,” she said. “He was just like any other white man. That fear had been out of me a long time.”

He was just like any other white man . When Catherine Burks-Brooks stared into the face of evil, it blinked.

Stranded in rural Tennessee — the "train depot" where Connor claimed he was taking them was just an empty warehouse, they looked for a Black family in the predominately white area who would take them in for the night.

After about a mile, they saw light coming from a back room in a shotgun house. In “an act of desperation,” they took a chance and knocked on the door, and Lewis told the black man who answered that they were Freedom Riders.

“Please let us in,” Lewis said. “We’re in trouble.”

Probably scared that he would be killed if he was discovered harboring them, the man refused.

But the students didn’t give up. Burks–Brooks said her mother had always told her to try to talk to “the lady of the house,” so they knocked and talked a bit louder.

Burks-Brooks was right. The "lady of the house" heard them and let them inside. The next day, they traveled hostile terrain and made it back to Birmingham, perhaps later than "high noon," but this likely still surprised the hell out of Connor.

“He was not stopping us,” Burks–Brooks said. “He was just slowing us down. We were just not going to tuck tail and go on back to Nashville, or we wouldn’t have been here in the first place.”

Two days later, white people viciously attacked the Freedom Riders at the Montgomery Greyhound bus station. Burks-Brooks later described the sadistic assault on Jim Zwerg — a white man who stood up for justice: “Some men held him while white women clawed his face with their nails. And they held up their little children – children who couldn’t have been more than a couple years old — to claw his face. I had to turn my head back because I just couldn’t watch it.”

Undaunted, Burks-Brooks and other heroes went on further freedom rides and even served time in Mississippi. Burks-Brooks would later display her defiant mugshot in her living room.

Time eventually bested Catherine Burks–Brooks, but no white man ever did.

[ Tennessean / Bk2bama / AL ]

Follow Stephen Robinson on Bluesky and Threads.

Catch SER on his new podcast, The Play Typer Guy.

Did you know SER has his own Substack? Well, now you do, so go subscribe right now!

Click the widget to keep your Wonkette ad-free and feisty.