So Now The New Yorker Is Doing Fox News's Job?

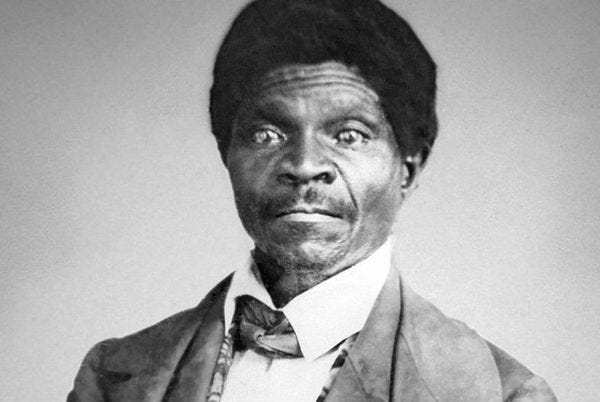

Nobody's canceling Dred Scott. At least, not any more than in 1857.

Wow, did you hear about those crazy libs who want law schools to stop teaching about the Supreme Court's 1857 Dred Scott decision because they're worried it'll trigger their snowflake students? It must be true, because it was covered by the New Yorker, not Ben Shapiro or OAN. This is where we point out that nothing of the sort has happened: Nobody's canceling Dred Scott v. Sandford in law schools, but the New Yorker did run a piece Tuesday suggesting it might be endangered . Problem is, the think piece was inspired not by a movement in law schools, but by a single Twitter discussion the author had seen, which suggested that the case might best be taught without reading much of the actual Supreme Court decision, because do you really need to wallow in all that racism?

The column, by Harvard Law prof and New Yorker contributor Jeannie Suk Gersen, makes a pretty strong argument for teaching Scott as an illustration of how norms of legal reasoning can result in a decision that's antithetical to human rights. It's actually a pretty good read, as long as you set aside the minor detail that it's all based on knocking down a straw man.

To be fair to Gersen, what might have been a pretty good think-piece on how to teach something as toxic as the Scott decision got lost in the New Yorker 's own ham-handed framing of the story, as I'll discuss in a moment. First, though, I want to say that Gersen's discussion of the case's place in law school seems pretty spot-on (this is where I remind you I'm a rhetorician, not a lawyer). Gersen argues the decision by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who himself was an enslaver, isn't so much an impossibly bad legal argument on its face as it is a warning to "disabuse students of the impulse to approach the Constitution and the Supreme Court with uncritical worship."

I hadn't really read much about the decision itself, only the outcome, which was that Dred Scott, who freed himself from slavery and made it to Illinois and then to free territory, didn't have the right to sue to prevent being re-enslaved, because as a Black person, he could not be a US citizen. What I hadn't known about was Taney's awful reasoning about those "inalienable rights" in the Declaration of Independence:

If the Founding Fathers intended to include Black people in that declaration while personally enslaving them, Taney reasoned, that would mean that the Founding Fathers were hypocrites who "would have deserved and received universal rebuke and reprobation." But Taney found it impossible that these "great men" acted in a manner so "utterly and flagrantly inconsistent with the principles they asserted." So he concluded, instead, that their intent was to exclude Black people from the American political community. Of the two possibilities, grotesque hypocrisy or white supremacy, Taney found the latter far more plausible.

And Taney had a point! A Critical Race Theory point, which is unexpected from someone who enslaved people, but a point! A point that would back up every "crazy" San Francisco decision to take Jefferson or Washington's names off all the elementary schools, so: A point!

The rest of the decision is grotesque. Throughout, Taney takes it as a given that African Americans aren't fully human, and therefore only worth consideration as property. It's pretty foul white supremacist stuff.

In any case, the Twitter discussion that sparked the article wasn't about removing Scott from law schools, but about how it should be taught. University of Buffalo constitutional law prof Matthew Steilen said he thought the case could best be taught by editing the decision down to a page or so of summary, because, he said, why traumatize students with all Taney's racist, dehumanizing language, when the legal principles — or Taney's perversion of them — can be taught without rubbing students' noses in Taney's racist words.

"I'm white and I'm going to stand up there and talk with the students, including Black students, about this stuff? I would be dragging them through stuff that was hurtful to them. . . . It just felt indefensible." Steilen feels that Taney's language "gratuitously traumatizes" readers: "I wasn't comfortable giving his words to my students because I was afraid it would hurt them and destroy the kind of community I want to foster in class."

Gersen also mentions another law prof who has decided to teach Scott without requiring students to read the full decision, and that both that professor and Steilen "came to these conclusions without pressure from students; they said they had not heard concerns or complaints." It certainly seems like a justifiable position, as is Gersen's point that to really understand the bogus constitutional argument, the full horror show should be taught, as you'd examine a tumor. But again, nobody's saying we should deep-six Scott .

The New Yorkerdidn't do Gersen any favors in its framing of the story, either. A subheading certainly implies this is a real, not a hypothetical problem: "By limiting discussion of the infamous Supreme Court decision, law-school professors risk minimizing the role of racism in American history." Thetweet promoting the story was even worse, turning the column's discussion of how Scott should best be taught into a "debate" over removing the case from law schools altogether:

A debate has erupted over whether the reviled Supreme Court case of Dred Scott v. Sandford should be excised from l… https: //t.co/nW5k6ENOUs

— The New Yorker (@The New Yorker) 1623175923.0

And hooray, now it's time for the fake — or charitably, misplaced — outrage party to kick into high gear. Whatever nuance there might have been in Gersen's discussion went out the window, because if you don't subscribe and didn't want to burn one of your limited New Yorker reads on this article, all you know is that a debate has "erupted" over "excising" the case from law school curricula.

As blogger and Twitter eminence Parker Molloy points out, the replies to that promotional tweet "fall into precisely two points of view." Folks who only saw the tweet expressed outrage at the supposed controversy, and folks who had read it, or who had at least read other discussions of it, pointed out the entire discussion involves "a single tweet thread from a single law professor."

The problem is, all that "wait, no, you've got it wrong!" tends to get lost, and you can bet we'll now be seeing endless complaints about whiny liberal college students demanding their professors water down legal history, because that's how a good cancel-culture panic goes, regardless of the facts.

[ New Yorker / The Present Age ]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please give $5 or $10 a month so we won't be cancelled, or have our best dirty jokes excised.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

yeah, but for 4 years it was - policy was released via tweet, as was hire/fire decisions. the media have not caught on yet that this is no longer a norm (in the vaguest sense of the word)

It was a movie first, out in 1973. The Paper Chase. John Houseman reprised his role in the TV series.