Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks For Confederate Homeschoolers

Before we get started, a note on a personal milestone: Last week marked the one-year anniversary of this feature, which began with a look at an American Literature book for Christian students, where we learned that Mark Twain rebelled against God's authority. Based on the amount of derp being thrown at the homeschooling market, we don't expect to run out of material anytime soon.

This week, the Civil War. And both of our textbooks actually do call it that, which is something of a relief (although our 11th/12th-grade text from Bob Jones University Press, United States History for Christian Schools (2001), uses the chapter heading "War Between the States.") And neither textbook explicitly plays the "It wasn't really about slavery at all" card, although they leave plenty of room for instructors to do so. Somewhat surprisingly, our 8th-grade America: Land I Love (A Beka Book, 1994), which usually does the most editorializing, is fairly quiet on the "why" of the Civil War, instead presenting a chronology of the events and debates leading up to the war, but leaving analysis up to the teachers or parents using the book.

U.S. History, on the other hand, is happier than usual to make judgments about good guys and bad guys. For instance, somebody at Bob Jones University Press simply does not care for John Brown. Where Land I Love describes him only as "an abolitionist who ... stirred up trouble in Kansas," U.S. History says

John Brown was a fanatical abolitionist from Connecticut who had come to Kansas to help win the territory for the antislavery forces. A failure in every business venture he attempted, Brown proved frighteningly successful as a terrorist.

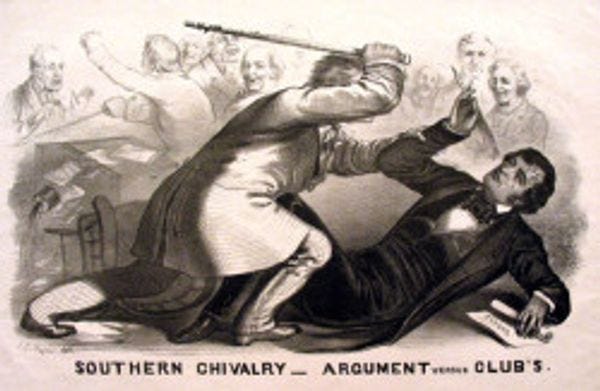

And there's no mere "stirring up trouble" in this textbook; instead, we learn that Brown, already enraged by the 1856 border attack on Lawrence, Kansas, was driven to madness when he learned that Rep. Preston Brooks had attacked and beaten Sen. Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate:

Brown, in the words of his son, "went crazy -- crazy." Gathering his followers about him on the night of May 24-25, this grim, self-styled "avenging angel" attacked several proslavery families along Pottawatomie Creek. In the grislyPottawatomie Massacre,Brown’s men butchered five proslavery settlers with razor-sharp swords.

The first reaction was almost universal horror among both pro- and antislavery groups. As news of the massacre traveled east, however, antislavery forces changed the story to suit their views. Northern newspapers claimed that the killings had been in self-defense, or that Indians had done it, or even that Brown had not been anywhere near the site of the killings. A congressional investigating committee, thanks to an antislavery majority, suppressed testimony condemning Brown. The "avenging angel" soon found himself free to pursue other plans[.]

And so you see, children, media bias has always been with us, which is why the lamestream media and liberals in Congress keep covering up the truth about Benghazi.

The aftermath of Brown's failed 1859 raid on the federal armory at Harper's Ferry gets similar treatment:

On December 2, 1859, John Brown’s body swing from a gallows in Charlestown, Virginia, but this was no routine execution. It was the inauguration of a period of mourning in the North that shocked the South by its excess. Buildings were draped with black bunting, church bells rang their dirges, and poets and pulpiteers poured out their most eloquent words on Brown, so recently convicted for murder and treason. Abolitionists found his death a useful symbol, and writers such as Emerson, Thoreau, and Louisa May Alcott, in words frankly blasphemous, compared Brown to Christ. Ironically, Thoreau also called Brown 'an angel of light,' apparently unaware that this was a Scriptural name for Satan (II Cor. 11: 14). In that context, most Southerners would have heartily agreed with Thoreau.

The majority of Northerners, however, did not support slave revolts or Brown’s methods. Lincoln noted that although Brown "agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong, that cannot excuse violence, bloodshed and treason."

Louisa May Alcott, blasphemer. (Incidentally, Brown and Frederick Douglass are given a fictional going-over in a new novel, The Good Lord Bird, which we have downloaded but haven't read yet. Perhaps we will review it, who knows?)

Anyway, on to the Causes Of The War, which U.S. History approaches with David Broderesque even-handedness:

Mr. Lincoln’s War, Jeff Davis’s War, War of the Rebellion, War for Southern Independence, War of Northern Aggression, War Between the States, the Civil War, the Needless War. People neither then nor now can even agree on what to call the war, much less what caused it. A number of complex, competing forces, however, converged and clashed to produce the bloodiest chapter in American history.

Of course, while there are many differing opinions, U.S. History is careful to note that "the institution of slavery was not the primary cause of the war," while granting that it was "a highly charged, emotionally divisive issue among certain influential groups in the North and South." Ultimately, it was a philosophical argument over the Constitution, very high-minded stuff:

The central issue that sparked the Civil War concerned the nature of the Union. Could states that voluntarily joined the Union by ratifying the Constitution voluntarily leave the Union? This was hardly a novel question in 1860; it had been hotly debated since the earliest years of the Republic.

And the textbook also quotes "the warmakers themselves" to demonstrate that secession was central:

The war resolution approved in the House of Representatives on July 22, 1861, by a vote of 121 to 2 stated plainly that

in this national emergency, Congress, will recollect only its duty to the whole country; that this war is not waged on their part in any spirit of oppression, or for any purpose of conquest or subjugation, or ... of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions of those States, but to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution, and to preserve the Union with all the dignity, equality, and rights of the several States unimpaired; and that as soon as these objects are accomplished the war ought to cease.

The textbook does not, on the other hand, quote from South Carolina's declaration of secession, which does indeed lay out a defense of the state's right to dissolve its connection to the Union, while mentioning slavery and the inalienable right to hold slaves as property some 18 times. As to how the book actually gets used in classrooms, it may be telling that in the copy of U.S. History that we bought on Ebay, the only paragraph part of the two-page discussion of "causes" that's outlined in yellow highlighter is this:

For their part Southern leaders asserted the constitutional right of secession based on state sovereignty. According to thestates’ rightsview, each state was largely an independent entity joined in a compact of union but a union in which they maintained their identity and were not subservient to a centralized national authority.

We're guessing that the previous owner of the textbook knew exactly what was going to be on the test for this section. The discussion of "Union vs. Independence" closes with a reminder that history and law are literally written by the victors:

Thus the war opened with the constitutional, questions and countercharges that had been haggled over for decades. The North argued that the Union must be preserved above all else; the South argued that the rights and liberties of the states must be preserved, even at the expense of the Union. Now the questions would be settled on the battlefield. Whoever won the coming war would get to stamp their interpretation on the Constitution.

Once again, this is from a textbook that elsewhere has no difficulty railing against the evils of moral relativism or seeing God's hand at work in historical events. But on this central question of how American government should work, the authors shrug and say, Hey, that's the breaks. The North won, whatcha gonna do? Maybe next time...

Next Week: Both sides had heroes, like "Robert E. Lee: Great Christian General."

if E.T. had owned one, would we have considered him a God? Look at how much mileage we got out of one dropped glass bottle

so beer and whiskey led to the Civil War. That explains a lot