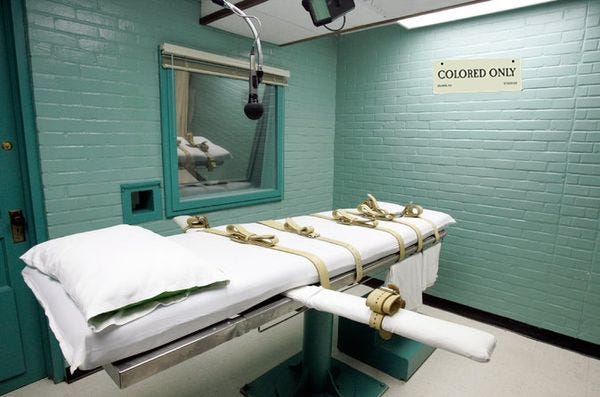

Supreme Court Rules Prosecutors Must Hide Racism More Effectively In Death Penalty Cases

The U.S. Supreme Court decided Monday that the Constitution only allows racial bias in jury selection when it's a lot more subtle than that practiced by a Georgia prosecutor's office 29 years ago. The court overturned the conviction and death sentence of Timothy Tyrone Foster, who was convicted by an all-white jury in 1987, a year after the Supreme Court held in Batson v. Kentucky that jurors could not be excluded solely on the basis of race. The Court decided Monday that prosecutors had systematically excluded blacks from Foster's jury; Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that "prosecutors were motivated in substantial part by race" in excluding two members of the jury pool, adding that two such strikes "on the basis of race are two more than the Constitution allows."

As with all stories about capital punishment, Yr Wonkette wishes to emphasize that we are definitely not in favor of murder, nor do we discount the suffering of victims and their families. Convicted murderers should not be set free unless evidence exonerates them, but we also don't think anything is helped when the state kills people, either. We also wish, somewhat forlornly, that the justice system would now and again involve some fairness in prosecution and administration of justice, wild-eyed radicals that we are.

We would also note: what a difference Scalia makes! We are old enough to remember his dissenting opinion that actual innocence was no impediment to a fair execution.

The AP points out that in his original trial,

Foster’s trial lawyers did not so much contest his guilt as try to explain it as a product of a troubled childhood, drug abuse and mental illness. They also raised objections about the exclusion of African-Americans from the jury. On that point, the judge accepted prosecutor Stephen Lanier’s explanations that factors other than race drove his decisions. The jury convicted Foster and sentenced him to death.

Stephen Bright, Foster's attorney, said "there is no doubt" the Supreme Court decision will result in a new trial for Foster, who was convicted of murdering a 79-year-old white retired schoolteacher. The court's decision was 7-1, with only Clarence Thomas dissenting. Thomas cited the brutality of the crime, noting that Foster had killed the victim "after having sexually assaulted her with a bottle of salad dressing,” and argued that the new evidence submitted in the case -- prosecutors' notes specifying the race of jurors and singling out potential black jurors to be stricken -- "does not justify this court’s reassessment of who was telling the truth nearly three decades removed from" the jury selection. The other justices disagreed.

When the case was argued in November, the justices did little to hide their distaste for the tactics employed by prosecutors in north Georgia. Justice Elena Kagan said the case seemed as clear a violation “as a court is ever going to see.”

Still, Georgia courts had consistently rejected Foster’s claims of discrimination, even after his lawyers obtained prosecutors’ notes that revealed their focus on the black people in the jury pool. In one example, a handwritten note headed “Definite No’s” listed six people, of whom five were the remaining black prospective jurors.

The sixth "definite no" was a white woman who said she was opposed to the death penalty and would never impose it, but the prosecutors actually ranked her as less objectionable to them than any of the black jurors, according to Bright.

The prosecution notes were obtained by Foster's attorneys in 2006 in response to a request using Georgia's Open Records Act. And they were a doozy:

The name of each potential black juror was highlighted on four different copies of the jury list and the word “black” was circled next to the race question on questionnaires for the black prospective jurors. Three of the prospective black jurors were identified in notes as “B#1,” ”B#2,” and “B#3.”

An investigator working for the prosecutors also ranked the black prospective jurors against each other in case “it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors.”

The prosecutor in Foster's trial, Stephen Lanier, insisted at trial that reasons other than race were used to exclude black jurors; the Death Penalty Information Center points out that the prosecution actually undermined the credibility of that claim by offering "eight to twelve reasons for each strike of a black juror and added even more reasons after trial"; in addition, some of the offered reasons were just plain untrue, like saying one black juror was a social worker when she wasn't. A 34-year-old black woman was stricken from the juror pool because she was supposedly close in age to Foster, who was 19 when he was tried, but prosecutors accepted eight white prospective jurors under the age of 35. Imagine that!

The AP notes that Foster's case is rare, in that "the prosecutors’ files contained clear evidence of racial discrimination," making the Supreme Court's decision relatively easy, and clearly conveying the message to prosecutors: they must never discriminate in jury selection, or at the very least, they'd better not leave any concrete evidence of it.

If premeditated killing is wrong, we shouldn't be doing it. Life in prison is plenty. Also, you can't un-execute someone if new evidence is found.

That's one clause in my contract I keep trying to get Rebecca to budge on.