That Time Colorado Took The Side Of ... The Workers???

February 7, 1894, in labor history!

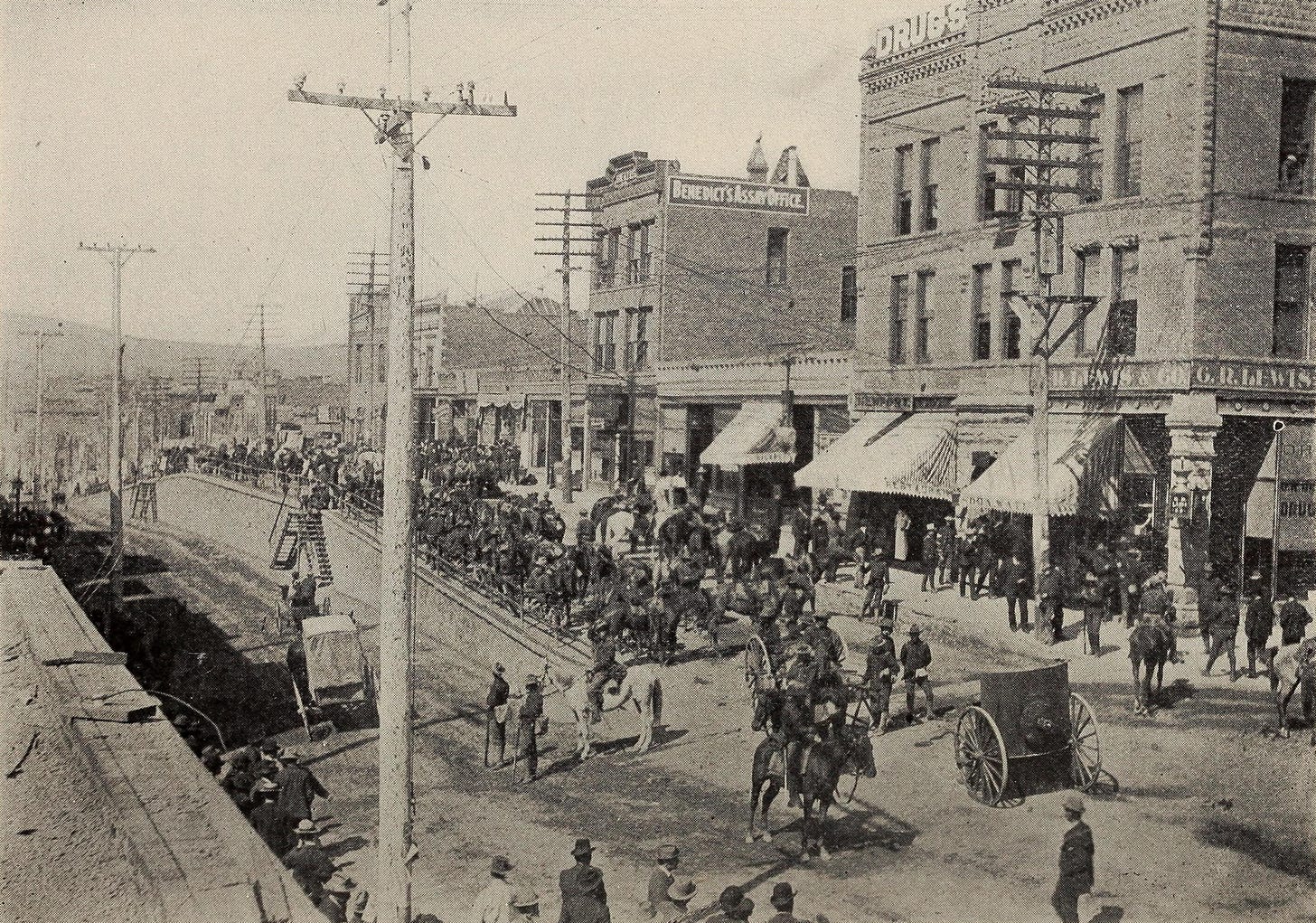

On February 7, 1894, gold miners near Cripple Creek, Colorado, walked off the job, leading to one of the biggest victories for organized labor in the Gilded Age after the state of Colorado intervened on the side of the workers. This strike made the Western Federation of Miners the major labor organization among western miners, as well as having a reputation for violence that made it unacceptable to conservative labor leaders in the American Federation of Labor. Importantly, it also shows how critical it is for workers to get the state to at least be neutral in conflicts between workers and employers.

My major thesis about American labor history is this: The US has an unfortunately tight relationship between corporations and politicians, more so than other similar nations. What that has meant is that corporations have usually demanded the government intervene in labor relations to tilt the playing field toward them. Government usually complies. Historically, unions have almost never won strikes when the state intervenes on the side of corporations. But if workers can express enough political power to move the state to neutrality, unions can definitely win. The Cripple Creek strike is a great example of this.

By the 1890s, the area around Cripple Creek was the center of the Colorado gold fields. Cripple Creek itself was the second largest city in the state. The Panic of 1893 theoretically could have helped these workers; it was silver prices that collapsed and the government needed all the gold it could get. But this led silver miners to flood into the mines and convinced the mine owners to lower wages. Raising the workday from eight to 10 hours with no pay raise led the miners to walk out.

The strike was widespread and effective. By the end of February, virtually every gold mine in Colorado was shut down. A few owners gave in and restarted their mines after retreating back to the eight-hour day. However, the big mines were intransigent and brought in scab labor. At first, the WFM tried to organize these men into the union. But work was scarce in 1894 and even a low-paying job with long hours was too good to pass up. So on March 16, a group of armed miners captured and beat six sheriff’s deputies heading up to a mine at Victor, where they were to assist in the protection of scabs.

This act led El Paso County Sheriff M.F. Bowers to request state militia intervention from the governor, the Populist Davis Waite. Waite was not the preferred governor for Colorado capitalists. When he realized that Bowers was lying to him about the extent of violence and really wanted a state strikebreaking force, he withdrew the militia. Bowers then arrested the strike leaders, but a jury found them not guilty of trumped up charges. Meanwhile, the strikers began to attack the scabs, throwing bricks and getting into fistfights with them. The mine owners then attempted to negotiate with the miners, offering a return to the eight-hour day but at reduced pay.

When the miners rejected this offer out of hand, and with the refusal of Governor Waite to use the militia as the personal army of the mine owners, the owners decided to raise a private army of their own. They paid for an army of 100 men, mostly ex-policemen, to become sheriff’s deputies and protect the hundreds of scabs they intended to bring to the mines.

When the miners heard about this, they organized to defend themselves. On May 24, they took over the Strong Mine, near Victor. When 125 deputies marched to take it, the miners blew it up. The deputies fled and the miners wanted blood. They filled a railroad car with dynamite and sent it down the railroad track, hoping to cause an explosion in the deputies’ camp, but it derailed. Many wanted to systematically blow up the mines. This didn’t happen, but tensions rose even further when the mine owners paid for an additional 1,200 deputies for their private army.

Fearing a complete massacre, Governor Waite stepped in. In an extremely rare move for the Gilded Age, Waite issued an order declaring the owners’ private army illegal and ordered the capitalists to disband it, sending in the state militia as a peacekeeping force. He then went to the miners and got their approval to be their bargaining agent with the mine owners.

To say the least, the mine owners were apoplectic. This was the age of the Great Railroad Strike, of Homestead, of Pullman. Capitalists expected the state to do their bidding. When Waite called a meeting of the union and owners in Colorado Springs, a mob whipped up by the companies formed outside and threatened to lynch Waite and the unionists. Through a decoy, they snuck out the back door and escaped. Despite this, Waite forced the mine owners to agree to restore the eight-hour day at the previous wages of $3 a day (in contemporary dollars, basically the equivalent of about $9 an hour for extremely dangerous work).

Even though they had reached an agreement, mine owners wanted revenge. Bowers could not control the 1,200 deputies. After a confrontation with the state militia at Victor, the deputies went to Cripple Creek, where they arrested hundreds of miners on trumped up charges. They even formed a gauntlet and forced townspeople to run through it while being beaten. The state militia then rounded up the deputies, essentially arresting the police. The mine owners refused to disband the private army but the governor said he’d keep the militia in town for another month which meant that the owners would have to pay the private army to do nothing. Finally, they gave up. It was arguably organized labor’s biggest win in the entire Gilded Age.

Governor Waite was seen by the respectable people of Colorado as a promoter of anarchy and was defeated in his reelection campaign in the fall of 1894, effectively ending the Populist movement in Colorado.

The Western Federation of Miners went on to play a key role in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, although it remained independent of that organization. It later became the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers (or Mine, Mill for short), one of the communist-led unions that the CIO eventually kicked out of the organization in the 1940s. It is probably most famous today for having produced the film Salt of the Earth, detailing a mining strike in southern New Mexico in the early 1950s. It finally merged with the United Steelworkers of America in 1967.

Cripple Creek itself became a gambling town in the 21st century in a state attempt to revitalize its old mining towns. Although less ravaged and gross than Black Hawk, which has become a gambling mecca for Denver that has completely obliterated the historical character of the town, the gambling has made Cripple Creek pretty unpleasant without providing many of the promised jobs.

FURTHER READING:

Elizabeth Jameson, All That Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek

Mark Wyman, Hard Rock Epic: Western Miners and the Industrial Revolution, 1860-1910

https://bsky.app/profile/blue-rosary52.bsky.social/post/3meccncldzs2r

MAGA erupts in rage as the city of Minneapolis gets nominated for the 2026 Nobel Peace Prize amidst their valiant resistance to Trump's violent ICE crackdowns.

Oh my goodness I wonder who it could be?

NSA detected phone call between foreign intelligence and a person close to Trump

Whistleblower says that Tulsi Gabbard blocked agency from sharing report and delivered it to White House chief of staff

You won't see The New York Times or Washington Post cover this. We got to go to the UK Guardian!

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/07/nsa-foreign-intelligence-trump-whistleblower

Last spring, the National Security Agency (NSA) detected evidence of an unusual phone call between an individual associated with foreign intelligence and a person close to Donald Trump, according to a whistleblower’s attorney briefed on the existence of the call.

The highly sensitive communique, which has roiled Washington over the past week, was brought to the attention of the director of national intelligence (DNI), Tulsi Gabbard – but rather than allowing NSA officials to distribute the information further, she took a paper copy of the intelligence directly to the president’s chief of staff, Susie Wiles, the attorney, Andrew Bakaj, said.

One day after meeting Wiles, Gabbard told the NSA not to publish the intelligence report. Instead, she instructed NSA officials to transmit the highly classified details directly to her office.

Details of this exchange between Gabbard and the NSA were shared directly with the Guardian and have not been previously reported. Nor has Wiles receipt of the intelligence report.

A press secretary for the office of the director of national intelligence (ODNI) said to the Guardian in a statement: “This story is false. Every single action taken by DNI Gabbard was fully within her legal and statutory authority, and these politically motivated attempts to manipulate highly classified information undermine the essential national security work being done by great Americans in the Intelligence Community every day …

“This is yet another attempt to distract from the fact that both a Biden-era and Trump-appointed Intelligence Community Inspector General already found the allegations against DNI Gabbard baseless,” the statement continued.