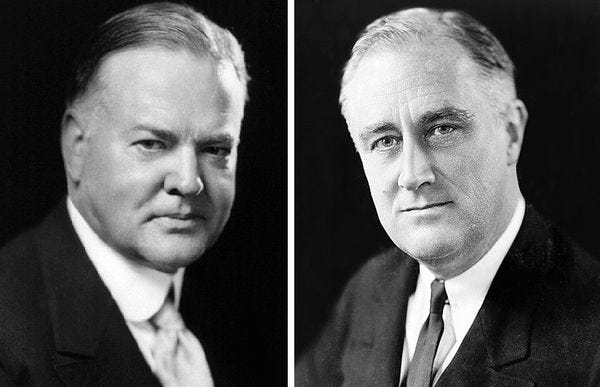

That Time Hoover Tried To Murder The New Deal Before It Even Started

Wonkette Book Club: Winter War, by Eric Rauchway

Grab your wine or coffee (or both, weirdo), because it's Book Club time! Remember, the cafe is kind enough to let us meet here, so buy a cookie at least. Our April selection is Winter War: Hoover, Roosevelt, and the First Clash Over the New Deal , by Erich Rauchway, a history prof at the University of California, Davis, and a scholar of the New Deal. Don't worry if you haven't done all the assigned reading for today (through Chapter 4), you can still participate, because come on, does everyone always do the reading? We'll only laugh at you if you suggest, like Ben Shapiro, that the New Deal worsened the Great Depression. Or if, like Dinesh D'Souza, you say Roosevelt admired Hitler (a claim Rauchway recently demolished on the Twitters). But you see, then you'd deserve it.

Winter War (buy it with this Amazon linky and Wonkette gets a nice little kickback!) looks at the New Deal from a fresh perspective: the period between Roosevelt's 1932 election victory and his inauguration in March 1933. In particular, Rauchway dissects Herbert Hoover's extraordinary efforts to sabotage Franklin D Roosevelt's plan in the long lame-duck period before Roosevelt could actually start putting his ideas to work. As it happens, thanks to the 20th Amendment -- passed by Congress in 1932 but ratified only months before he took office -- Roosevelt was the very last president to face such a long interregnum (a word you know Donald Trump probably thinks has something to do with pulling out early). That gave Hoover plenty of time to try -- mostly unsuccessfully -- to undermine his successor and his program, which Hoover was convinced would Ruin America Forever.

Rauchway crams a hell of a lot of thematic matter into those four months (OK, fine, yes, he looks beyond them, too, because historians are like Tralfamadorians that way, even if they seldom say "So it goes"). He has a fun eye for detail, and while the book is definitely fair, there's also no doubt he's an FDR fan, which, what with the four terms and all, seems to be on the right side of history, innit?

Hoover certainly left no shortage of material to help historians depict him as a humorless prig who put his ideology ahead of the evidence, and even ahead of recommendations from his own advisers. I hadn't known all that much about Hoover, apart from a general sense of him being a free marketeer who lost the 1932 election because nobody was buying his insistence that the Depression would end on its own. As I read Winter War, I come away saying, "Wow, what an asshole!" every few pages. They tend not to be the Roosevelt pages, with one seriously notable exception, more about which in a bit.

In a sense, Hoover's opposition to Roosevelt partly succeeded, at least as a matter of Republican politics, well beyond the 1930s. The New Deal became reality, but Hoover was able to make opposition to it, and to government assistance to anyone who wasn't already well off, a central tenet of American conservatism. It's such a fundamental Republican belief that we tend to think of it as foundational, but as Rauchway demonstrates, Hoover set up the party's permanent booth at the Laissez Fair. Even during the 1932 election, prominent Republicans and his own advisers urged Hoover to do more to help people who'd lost their jobs, but he'd have none of it, because damn it, opposition to government meddling in the economy was his guiding principle, and he was determined to make it THE Republican principle.

As Hoover put it, if the Republicans had an "Ark of the Covenant," an unremitting opposition to the New Deal would be graven, still discernible, on the divine fragments within. After his electoral loss, he set about ensuring institutional support for this notion, seeking to create a conservative media, inculcate young Republicans into his beliefs, and ensure that party leaders supported his views.

Hoover was convinced that "The depression reached its turning point in the Spring of 1932… [and that recovery] started up under our 'Old Deal,'" and nobody was going to convince him otherwise. You'll find plenty of conservative revisionists for whom that has indeed become an article of faith -- remember those conservative Christian textbooks preaching that the Depression itself was caused and worsened by government regulation? And for that matter, as one such text proclaimed, the severity of the Great Depression was exaggerated in the first place, by Radical America-haters, who

spread rumors of bank mortgage foreclosures and mass evictions from farms, homes, and apartments. But local banks did all in their power to keep their present tenants. The number of people out of work in the 1930s averaged about 15 percent of the work force; thus 85 percent continued to work. Most had to take a pay cut, but prices also declined during the Depression, enabling people to buy more for their money.

Sure, times were tough, but people looked to God and would have been just fine if Roosevelt hadn't sneaked a lot of socialism into American life. (Hey! That was a good series! I really should make it an e-book, in my "spare time"!)

Not a lot of doubt about Hoover's lasting influence in conservative circles; Winter War details how Hoover set about shaping that Republican orthodoxy even after he lost in 1932, although Rauchway notes Hoover's machinations failed in one aspect: he had hoped for more immediate success. Certain the New Deal would utterly fail, and quickly, Hoover expected Americans to see just how right he'd been and sweep him back into the presidency in short order. Instead, he had to settle for shaping conservatism as permanent opposition to social justice and, if it got votes, outright cruelty, in the name of the myth of economic self-reliance. You can't read Winter War without seeing Hoover's well-manicured fingerprints all over today's politics.

Another thread in Winter War involves correcting a historical bias that I honestly hadn't been especially aware of: Rauchway seeks to rescue FDR from the accusation, popular with some late 20th-century historians, that FDR he was elected and governed as a charismatic but somewhat empty figure. In that framing, FDR was a glib opportunist who smilingly offered reassurances but almost stumbled into the New Deal not as a matter of conviction, but because he decided he might as well try something. That inaccurate depiction seems to have been at least partially shaped by Roosevelt's labor secretary, Frances Perkins, who wrote in her 1946 memoir that the New Deal

"was not a plan with form and content.… [It] expressed an attitude, not a program." She went on, "The notion that the New Deal had a preconceived theoretical position is ridiculous.… There were no preliminary conferences of party leaders to work out details and arrive at agreements." Historians have frequently echoed Perkins, particularly favoring the line, "Attitude, not a program."

Rauchway goes to some lengths to demonstrate that Perkins "may have been a great secretary of labor, but she was a poor historian: not a word of her remarks is true," noting the many very explicit campaign promises Roosevelt made during the campaign that became reality during his presidency, particularly agricultural price supports, unemployment relief through government jobs programs and big construction projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority, and Roosevelt's overall push to empower workers instead of capitalists. Rauchway archly notes that if Roosevelt had had no program heading into 1932, it would have been pretty difficult for Hoover to have warned that every part of FDR's agenda reeked of the "fumes of the witch's caldron which boiled in Russia and in its attenuated flavor spread over the whole of Europe."

We love a good history fight, and Rauchway is out to settle the hash of anyone who contends, pace Perkins, that Roosevelt made the New Deal up as he went along. That's no mere academic dustup, either, says Rauchway:

The argument that Roosevelt won the election without letting the voters know what he was going to do is an argument that the New Deal lacked democratic legitimacy. And democratic legitimacy was the most important thing Roosevelt could achieve: it was the New Deal's ultimate goal. A speedy recovery and support for (as it was then already called) social justice were goods in themselves, but they were even more important to the New Dealers because these successes could fend off a movement for fascism.

This is not to say that Rauchway is an uncritical Roosevelt fanboi. That becomes particularly clear in Chapter Four, which focuses on Roosevelt's coldly pragmatic view of race and the New Deal. Time and again, African-American leaders and their white progressive allies tried to get Roosevelt to emphasize he really meant ALL Americans when he'd promised to "resume the country's interrupted march along the path of real progress, of real justice, of real equality for all our citizens, great and small."

Joel Spingarn, the head of the NAACP (and a white dude, as was not unusual back then) wrote Roosevelt a letter urging him to promise he would fight for civil rights, noting that black voters in the North could ensure Roosevelt's margin of victory (plus, of course,t he whole doing the right thing for America bit). Spingarn discussed the letter with Roosevel's pal and adviser Henry Morgenthau Jr., who warmly recommended it to the candidate and wrote back to Spingarn, "I am quite sure you will hear from him directly."

That didn't happen, and Roosevelt remained stubbornly silent on matters of race, because he believed saying anything even remotely supportive of FULL equality would doom his support from Southerners and Westerners.

Although the governor responded promptly, he addressed only Morgenthau, and privately. "In reply to your letter of the 26th with enclosures from Mr. Spingarn," Roosevelt wrote, "just between you and me, as a matter of pure political expediency, the less I say about this subject, the better."

It was an amazingly cynical move, and very much at odds with Eleanor Roosevelt's far more activist stance, but Roosevelt and his official spokespeople would go only as far as saying the New Deal would lift up all Americans. Never a word that a Roosevelt administration would ever promise voting rights or other basic matters of equality. As the New Deal continued, Roosevelt again and again accepted concessions to Southern racists as the price for holding together his electoral coalition, even when he could have been more assertive.

Not that Hoover was any great shakes for African-Americans, either. Hoover was quite happy to court segregationists by discarding that old "party of Lincoln" stuff, going back to his days as secretary of commerce under Calvin Coolidge, when Hoover made a great show of generously helping out white victims of the Mississippi River floods of 1927 (soundtrack: Randy Newman's "Louisiana 1927" ). Black flood victims, on the other hand, could get flood relief only if they accepted what amounted to servitude under government bureaucrats, cleaning up flood damage. Once Hoover was president, he alienated even more African-Americans by nominating John J. Parker to the Supreme Court. Parker had advocated outright disenfranchisement of blacks during a 1920 run for governor of North Carolina:

"The Negro as a class does not desire to enter politics," he said. "The Republican Party of North Carolina does not desire him to do so. We recognize that he has not yet reached that stage in his development when he can share the burdens and responsibilities of government.… The participation of the Negro in politics is a source of evil and danger to both races."

Gee, that sounds a heck of a lot like William F. Buckley's "principled" opposition to desegregation in the 1950s, when he said blacks simply weren't "civilized" enough to handle full participation in democracy (oh, but he didn't think blacks were biologically inferior, just "culturally" not advanced enough, so good for him). Parker was rejected by the Senate, but the damage to Republicans in the black community was done.

Rauchway also deftly links Hoover's No Government Interference ideology with the racist states' rights agenda: If the federal government promises not to interfere in the economy, then by golly, it's certainly not about to go forcing integration on states determined to keep blacks second-class citizens. It's the same "principled" opposition to civil rights trumpeted by Barry Goldwater in 1964, and for that matter by Rand Paul today -- though of course he says he'd never UNDO the Civil Rights Act, just that it's worth having a "conversation" about the government's intrusion into the free market, you see.

There's plenty to detest both candidates for here; some prominent black newspapers made no endorsement in 1932, while others cautiously went with Roosevelt since, while he refused to reach out to black voters, he seemed less likely to openly harm them, and his economic agenda at least seemed more likely to be helpful, if lacking in specific help for black people. (Another Randy Newman lyric comes to mind: "Lord, If you will not help us, won't you please just let us be?"

And that's where we'll leave things for this week, even if it's a major bummer; we'll finish our discussion of Winter War in two weeks, onApril 21(yes, it's Easter, just New Deal with it), and we'll also figure out how we should include Dr. Rauchway in our discussion -- I was thinking maybe having you Terrible Ones ask him questions on the Twitter (or in email to me if you avoid that hell app) and then posting selected Q&A in an article in the week running up to Part 2 of our discussion? If you have other ideas, lemme know! Also, for the sake of keeping this a Book Club, could you please refrain from off-topic comments? We promise you a real Open Thread very very soon!

[ Winter War: Hoover, Roosevelt, and the First Clash Over the New Deal, by Erich Rauchway. Hardcover: $19.48, Kindle ebook: $18.99)

Yr Wonkette is supported by reader donations! Send us some money and we'll devote it to advocating for big government for all, YAY! And don't forget to pick up YOUR copy of Winter War today, with a nice kickback to Yr Wonkette!

An optimistic view of human nature, there. What did work, somewhat, was affirmative action: getting blacks into universities, and into positions of political and economic power, even if it meant ramming it down the throats of the racist yokels. It's hard to sit in a boardroom and propose redlining a neighborhood when there's a black person sitting at the table. Openly racist shit doesn't go far in state legislatures today, for the same reason. There's been a bit of backsliding thanks to the current Dipshit-in-Chief, but in the long run, that arc does keep bending.

Oh, I think that's settled beyond debate. Hoover was a statesman for the ages, compared to Il Douche.