That Time John L. Lewis (Different John Lewis) Did Some Good Trouble

November 9 in labor history!

On this date in 1935, United Mine Workers of America leader John L. Lewis and his allies created the Committee for Industrial Organization (later the Congress of Industrial Organizations). They were determined to drag the conservative labor movement into the 20th century and actually organize workers who really existed, as opposed to their nostalgic vision of 19th century-style skilled craft workers as the only legitimate people worth unionizing. The creation of the CIO revolutionized the American labor movement over the next decade.

Ever since the failure of the Knights of Labor to organize all workers behind the eight-hour day in 1886, the American labor movement was primarily dominated by the American Federation of Labor. Led by the cigarmaker Samuel Gompers, it provided a conservative alternative to the radical ideology America’s industrial workers were increasingly finding appealing. The AFL defined itself as a moderate alternative that industry should recognize as a bulwark against radicalism. In doing this, the AFL excluded people it deemed undesirable to its image — women, Black people, Asians, children, and the masses of eastern Europeans toiling in America’s huge factories. This kept the appeal of radicalism very real for millions of Americans who found themselves increasingly desperate for union representation. They would join left-leaning unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World, or join anarchist or communist groups.

Of course, there was often a major division between Gompers and the AFL leadership on one side and the rank and file on the other. On the ground, the AFL often served as a radical force for change in local communities, though, as in the Seattle General Strike of 1919, the federation would throw its radical workers under the bus if they threatened labor’s moderate reputation.

Not only was the AFL’s rejection of radicalism a problem, so was its organizing model. Seeing themselves as a group of skilled laborers who had trade consciousness but not class consciousness, Gompers and other AFL leaders rejected the idea of organizing by industry. Instead of organizing all auto workers into a single union, it would rather have 40 unions in the factory, each divided by the specific job one did. This fracturing undermined the ability of labor to act as a radical force for change, which was mostly fine by Gompers.

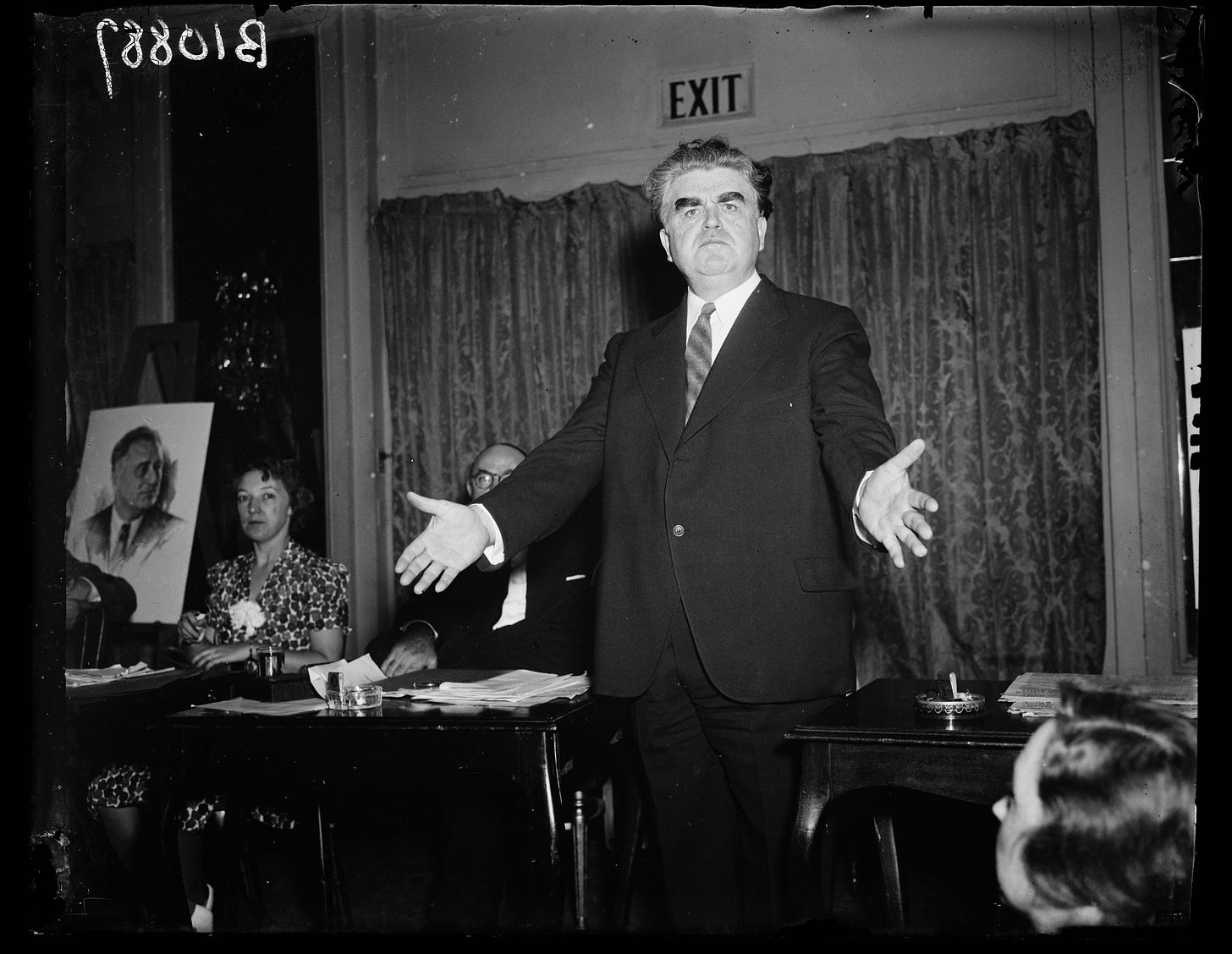

There were exceptions to this model. Probably the most important was the United Mine Workers of America. The UMWA came out of the incredibly brutal conditions of the late 19th and early 20th century Appalachian coal country, where companies ruled like lords over serfs, where violence against striking workers was commonplace, and where accidents took place at a rate similar to Chinese coal mines today. By the early 1930s, the UMWA was led by John L. Lewis. Lewis came out of the coal mines of the Midwest. Gompers hired him as a mining organizer in 1911 and by 1919, he became president of the UMWA. Lewis reinvigorated that union, calling a huge strike in 1919 that ended when Woodrow Wilson successfully won an injunction against them. Building on the still brutal conditions in coal country, Lewis used the nation’s dependence on coal to force better conditions for his workers, who were usually quite willing to strike. This made Lewis hated by the nation’s business leaders but a hero to many who sought a more aggressive unionism during the labor retrenchment of the 1920s. Although by no means a socialist (he was a Republican and a supporter of Hoover in 1928 and Willkie in 1940), he knew how important radicals were to labor organizing and happily used them to further labor’s aims.

By the early 1930s, the increased destitution of the Great Depression led to a huge spurt in union organizing. Pressure to organize workers on an industry-wide basis mounted. John Lewis, among others, led the fight to include industry-wide organizing within the AFL. The AFL tentatively moved ahead with this beginning in 1934, but refused to fund the efforts. Meanwhile, huge industrial strikes started taking place in the face of conservative AFL leadership, including the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike and the Longshoremen’s Strike in San Francisco, both in 1934. After AFL President William Green and his allies slighted industrial organizing at the 1935 AFL convention, which led to Lewis punching Carpenters’ president William Hutcheson on the floor of the convention, Lewis and his allies began planning to leave the AFL.

On November 9, 1935, the UMWA, along with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and other industrial unions within the AFL created the CIO. Originally, the CIO, then called the Committee on Industrial Organizations, operated within the AFL, but when Green continued dallying on industrial organization, Lewis and others decided to split entirely. The CIO would have a major impact on American history in coming years, organizing some of the biggest workforces in America, including steel workers, auto workers, rubber workers, and electrical workers. Among its early successes were the Flint Sit-Down Strike, the battles to organize the steel plants, and eventually organizing Ford in 1941, a major success both in concrete and symbolic terms given Henry Ford’s hatred of unions. Ford had ordered his personal thugs to beat up CIO organizers, including Walter Reuther, back in 1937, so this was a big one. By 1938, the CIO had 4 million members; by 1945, this number had risen to 6 million.

Despite its early successes, the CIO never surpassed the AFL in membership. For one, CIO competition forced the AFL to become more aggressive organizers. For another, infighting between competing AFL and CIO unions in an industry became endemic and undermined labor effectiveness. In the timber industry, the CIO created the International Woodworkers of America to compete against the AFL unions, which operated under the auspices of the Carpenters. The two union newspapers spent more time hating on each other than attacking the timber industry.

The CIO was effectively hamstrung by postwar McCarthyism, which forced its leadership to kick out the communists that had served as such effective industrial organizers. By 1955, differences between the AFL and CIO were pretty small. The CIO merged with the AFL and thus began a new era of conservative union leadership that still plagues the labor movement today.

FURTHER READING:

Robert Zieger, The CIO, 1935-1955

Ahmed White, The Last Great Strike: Little Steel, the CIO, and the Struggle for Labor Rights in New Deal America

Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine, John L. Lewis: A Biography

Robert Zieger, American Workers, American Unions: The Twentieth Century

Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor

James Green, The World of the Worker: Labor in Twentieth-Century America

Randi Storch, Working Hard for the American Dream: Workers and Their Unions, World War I to the Present

It is snowing here in Cleveland! It is coming down really good.

I am crying. I so envisioned this day when I was planning my move here. It would mean I made it from summer to winter. Something symbolic. Back then I needed to have this goal, making this move was so incredibly difficult and emotionally draining. I have been here almost 5 months and now I am home.

"Both teams practiced with wet balls this week."

Sideline announcer at the Browns/Jets game.

Phrasing!