October 29, 1889, In Labor History: The Hawaiian Island Lynching Of Katsu Goto

Can't owe your soul to the company store if there's another non-company store.

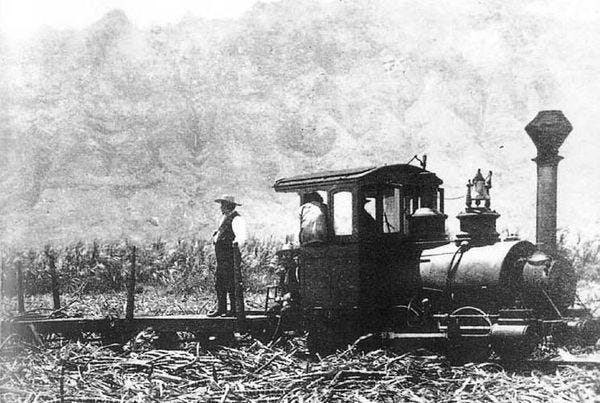

Nearly as soon as white missionaries arrived in Hawaii before the Civil War, they wrote back home about all the investment possibilities there. Soon, white Americans arrived to establish sugar plantations, wresting control of the islands away from the native Hawaiians and putting increasing pressure on the Hawaiian government to capitulate to planters' demands. Sugar is a labor intensive crop and there was no way that Hawaiian natives could supply it, especially as disease decimated their population. So the planters very quickly looked overseas. At the same time, many Japanese migrated to the United States for better economic opportunities. Many of them came to Hawaii. There, they were treated like dirt, much like Black agricultural laborers in the South.

Katsu Goto was one of the first laborers to come over. Born in 1862 in Kokufu-mura, Naka District, Kanagawa Prefecture, he worked for the Japanese government and learned English. In the early 1880s, the Japanese government worked out with the Hawaiian planters a migration plan. The Kanyaku Imin were these people, 29,000 contract laborers sent by the Japanese government between 1885 and 1894. Goto, wanting a different life than what he had in his government job, was on the first ship to arrive. He was a laborer under a three-year contract on the Big Island. After those three years, Goto decided to open a store to serve the Japanese community in Honoka'a, the second largest city on the island. This made the white merchants profiting off high prices angry. Of course, he did a better job of getting the products the workers wanted; moreover, he treated them like humans. He soon became an advocate for the heavily exploited Japanese laborers. The planters and their overseers routinely whipped the Japanese workers. Goto was disgusted. And because he spoke such good English, he also became the court representative for Japanese charged with crimes or for those trying to resist crimes against them by their employer. He also started to organize these workers to improve their working conditions.

On October 29, 1889, whites in Hawaii lynched him.

White planters in Hawaii wanted complete control over the Japanese workers and would use violence to achieve it. Five men, including the overseer of one of the plantations, ambushed Goto after an organizing meeting. Probably that plantation owner ordered his death. The next time anyone saw Goto, he was hanging from a telephone pole (or so it is reported today; I wonder if it wasn't actually a telegraph pole, but whatever), strangled to death.

Somewhat surprisingly, the five men were charged with Goto's murder. The Japanese government was furious. Two of the five turned state's witness and had their charges dropped. The other three were found guilty of manslaughter. Two escaped from prison, one to Australia and the other to California. Most likely, they had help from the planters to get out. The third served his four year sentence and then received a pardon from the new governor in 1894, after the planters had overthrown the Hawaiian governor, anticipating an annexation by the United States that would have to wait until after the anti-imperialist Grover Cleveland left power. Yes, this is probably the only good thing one can say about Cleveland.

The Hawaiian planters would continue treating their workers like slaves for decades – Hawaiian, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, and whoever else they could get in the fields. Finally, in 1920, a cross-racial strike between the Japanese and Filipino workers would lead to a major victory for the field workers.

WHY IT MATTERS

This now obscure story in American history matters for two major reasons. First, Goto is one of the unsung heroes of this country, a man who fought and died to bring justice to his people. That his life ended in this task says so much about the violent imperialism, colonialism, and racism that defines American history. We need to know these stories in order to understand the problems we have in our nation today.

That leads us to the second major reason to remember this story, which is the wave of anti-Asian violence washing over America in the wake of the COVID pandemic. Donald Trump and other Republicans using the virus to stoke anti-Asian hatred is just too typical of American history to ignore. Of course, people racist enough to beat up an 80-year-old woman over the pandemic have no idea if she is Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Thai, or anything else. They are all foreigners destroying us. This is the same hatred that killed Katsu Goto in 1889.

FURTHER READING

Gary Okihiro, American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islanders

Michael J. Pfeifer, ed., Lynching beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence outside the South

Thank you for keeping Wonkette in writers and labor history.