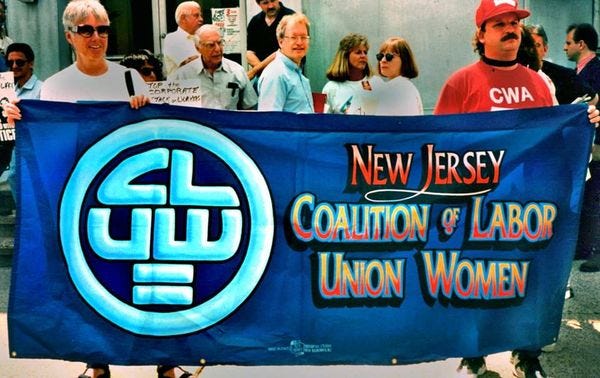

Today And Yesterday In Labor History: The Coalition Of Labor Union Women Aren't Here To Swap Recipes!

Pardon me ma'ams, this is a recipe hub.

On March 23, 1974, the Coalition of Labor Union Women formed. An organization within the AFL-CIO, the CLUW seeks to improve the standing of women within the union movement, as well as to organize more women into unions and promote union and legislative policies that help working-class women.

The labor movement has made a lot of progress in terms of gender equality. Women make up a large portion of organizing staffs, a growing percentage of executive boards, and international presidents like Randi Weingarten of the American Federation of Teachers. Sara Nelson has inspired the labor movement with her passionate defense of workers rights as head of the Association of Flight Attendants. Just recently, upon the death of AFL-CIO head Richard Trumka, the federation’s Secretary-Treasurer, Liz Shuler, became its first female president. This is major progress.

On the other hand, a male chauvinist culture still dominates a whole lot of unions. Any unionist who pays attention to these things knows it’s true. I’ve overheard too many conversations where someone has started talking about the women in the room like it’s a high school locker room. Some of this is perhaps class culture. Feminist language is far more accepted within the academy than the industrial workplace; for someone like me, it’s really jarring to hear inappropriate remarks about women when they may or may not be out of earshot. But it’s also quite obvious that working class people are not more sexist than academics or even rich capitalists. It’s that some unions remain places where men can talk this way without consequence. It’s a problem that needs to be eradicated from our unions.

This was all way worse in the 1970s. Women throughout American society were struggling for recognition of their rights and issues, including at the workplace. The feminist movement was peaking, challenging sexist notions throughout society. In the labor movement, it was nearly impossible for women to get their concerns voiced. They had no positions within the highest reaches of the AFL-CIO or in nearly any international. Sexism was entrenched in many union workplaces, and union representatives often ignored women's anger regarding bad treatment, including sexual harassment, wage disparities, and lack of promotion opportunities at the workplace and within unions. The problem was even worse for women of color. Some unions were better than others though; the United Auto Workers was the first union to come out in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment, in 1970.

The CLUW was created in June 1973 under the leadership of Olga Madar, vice president of the United Auto Workers, and Addie Wyatt of the United Food and Commercial Workers. Madar had risen through the UAW from her start with the union in 1941. She was most famous for spearheading the fight to desegregate the nation’s largest bowling organizations in 1952. She also led the UAW’s Conservation Department in the 1960s, lining up union support for environmental legislation and land protection. Wyatt was the first Black woman to hold an executive position within an American union, as VP of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters Union before moving to the UFCW. Wyatt was a major player in labor’s support for the Civil Rights Movement. She was also named, along with Barbara Jordan, Time’s Woman of the Year in 1975. These were very important people, way too forgotten nearly 50 years later.

After a few smaller organizing conferences around the country, 3,200 women met in Chicago on March 23 and March 24, 1974, for the CLUW’s foundational meeting. The meeting took a challenging tone to the chauvinistic attitudes of organized labor. Said Myra Wolfgang of the Hotel and Restaurant Employees and Bartenders Union, “You can call Mr. Meany and tell him there are 3000 women in Chicago and they didn’t come here to swap recipes!” The meeting set aside time for women to voice openly the problems they faced as trade union women. Like many moments in the feminist movement, the CLUW helped isolated women around the country realize there were many others who faced their predicament. It gave them a collective power not unlike the consciousness-raising meetings that marked the feminism of the early '70s. The CLUW announced its solidarity with Gloria Steinem and the National Organization of Women; in fact, Steinem was there as a representative of American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. In doing so, the CLUW leadership set the organization as a close ally of mainstream feminism, which alienated radical women to some extent, but probably made political sense in a climate where labor’s leadership was not particularly supportive of its existence.

Organized labor’s immediate response to all of this? The UAW sent a message of support. AFL-CIO President George Meany said nothing at all, as did most internationals.

The CLUW’s creation was an important moment and symbol. But we shouldn’t overestimate its ultimate importance. First, the organization never had a clear mission with tangible goals. Was it primarily a women’s organization or a labor organization? Second, there were a lot of generational tensions within the CLUW between the somewhat older women who led its founding and had pioneered roles for women within organized labor and younger women who demanded more radical positions, including signing up poor women who were not union members. I know from my own research that the local CLUW chapter in Seattle fell apart over the issue of radicalism, with less radical unionists accusing radicals of seeking to connect the CLUW to socialist organizations and those younger leftist women seeking to use this new organization to fight for the justice they saw as right.

The CLUW also tended to replicate the bureaucratic union structure it evolved from rather than embrace the worker democracy that union reformers of the period called for. Madar and Wyatt had a strong commitment to working within the established labor movement rather than challenging it from the outside. In fact, most of the highest ranking women union officials were extremely concerned about the CLUW saying anything or passing any resolutions that were openly critical of established union leadership. This same dynamic often hurts union reform efforts today. Women from the Teamsters threatened to walk out if the CLUW supported the United Farm Workers (the Teamsters were trying to beat out of the UFW – often literally – for jurisdiction to represent agricultural labor). So in many ways, the CLUW reflected the complexities of the labor movement as a whole in the mid-1970s.

On the other hand, the CLUW has been important in making sexual harassment an issue organized labor had to take seriously while pressing unions to fight for wage equality. Pay disparities actually grew during the 1960s. In 1960, women made 63.9 cents for every dollar earned by men. In 1970, it was 59.4 cents. By the end of 1974, there were 24 local CLUW chapters with 2500 dues-paying members. But this number was disappointing for CLUW activists; even worse was a decline in 1975. The CLUW eventually turned into a relatively small but still useful organization of labor union women pressing labor issues within the AFL-CIO. If it failed to revolutionize women’s roles within organized labor, well, that was hardly its goal in the first place.

The Coalition of Labor Union Women continues today , pushing for such recent victories as the renewal of the Violence Against Women Act, with the expanded protections Republicans fought to exclude from the bill. The organization also continues to hold meetings across the country to rally unionist women to push for both labor and gender equality.

FURTHER READING:

Dorothy Sue Cobble, ed., The Sex of Class: Women Transforming American Labor

Marcia Walker-McWilliams, Reverend Addie Wyatt: Faith and the Fight for Labor, Gender, and Racial Equality

Silke Roth, Building Movement Bridges: The Coalition of Labor Union Women

Enjoy this post? Help us pay Erik Loomis, if you are able!

Yep. Everyone on that show just *hated* doing master takes on the bridge - the director would yell for more action, and the sound guy would yell for less bumping and stomping. They needed a stagehand to run a lever that opened and closed the elevator doors, also too.

Those last two sentences should have had the "spoiler" tags for effect. Made me laugh!