Today In Labor History: In 1938, FDR Ends Child Labor, Creates Minimum Wage ... At A Cost

The Fair Labor Standards Act still needs to be fixed, too.

On June 25, 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act. This groundbreaking piece of legislation, while flawed as almost all progressive legislation must be to pass Congress, set the standards of labor that defined post-war America, including minimum wages, overtime pay, and the banning of most child labor.

Sweeping laws to regulate wages and hours had been bandied around for some time, including a bill sponsored by Alabama Senator Hugo Black in 1933 to reduce the workweek to 30 hours. Black continued to push for some kind of comprehensive labor regulation bill, although he had to fight against significant congressional opposition from conservatives. Roosevelt campaigned on wage and hour legislation in his 1936 reelection bid. In 1937, Black led a new fight for such a bill and it took nearly a year of contentious negotiations to make it happen.

Ending Child Labor Was Good For Business

On May 24, 1937, FDR had the bill introduced through friendly congressmen. The original bill included a Fair Labor Standards Board to mediate labor issues, and a 40 cent an hour minimum wage for a 40 hour week, as well as the prohibition of "oppressive child labor" for goods shipped between states. FDR told Congress, "A self-supporting and self-respecting democracy can plead no justification for the existence of child labor, no economic reason for chiseling worker's wages or stretching workers' hours." The administration tried to stress that this was actually a pro-business measure. Commissioner of Labor Statistics Isador Lubin told Congress that the businesses surviving the Depression were not the most efficient, but the ones who most ruthlessly exploited labor into longer hours and lower wages. Only by halting this cutthroat exploitation could a more rational and well-regulated economy result.

Organized labor was split on the FLSA. Many labor leaders believed in it wholeheartedly, including textile union leaders Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky. Interestingly, both AFL head William Green and CIO leader John L. Lewis supported it only for the lowest wage workers, fearing a minimum wage would become a maximum wage for better paid labor. This reflected the long-standing mistrust of government by labor, lessons hard-learned over the past half-century, but ones that could get in the way of understanding the potential of the New Deal.

All this happened while FDR was also engaged in his court-packing scheme. Roosevelt suffered major political damage from this idea and it threatened the FLSA's passage. It quickly moved through the Senate but the House stalled it. It was only after Claude Pepper beat off an anti-New Deal challenger in the Florida primary that enough southern Congressmen would vote for the bill for it to pass, even in somewhat weakened form. The bill FDR finally signed covered about 25 percent of the labor force at that time. It banned the worst forms of child labor, set the labor week at 44 hours, mandated overtime pay, and created the federal minimum wage, set at 25 cents an hour.

Corporations Outraged, Haven't Stopped Whining Since

Of course, corporate leaders howled about the impact of this 25 cent minimum wage. It was a big enough threat that Roosevelt addressed it in a Fireside Chat, telling Americans, "Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day...tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry."

The impact of this law cannot be overstated. The minimum wage had been a major project of labor reformers for decades. During the Progressive Era, reformers had made some progress, but the Supreme Court ruled a minimum wage for women unconstitutional in Adkins v. Children's Hospital in 1923, killing the movement's momentum. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 set an important precedent for federal regulation over wages and hours, but the Supreme Court overruled this in 1935, leading to the National Labor Relations Act later that year and FDR's attack upon the Supreme Court as an antiquated institution destroying progress.

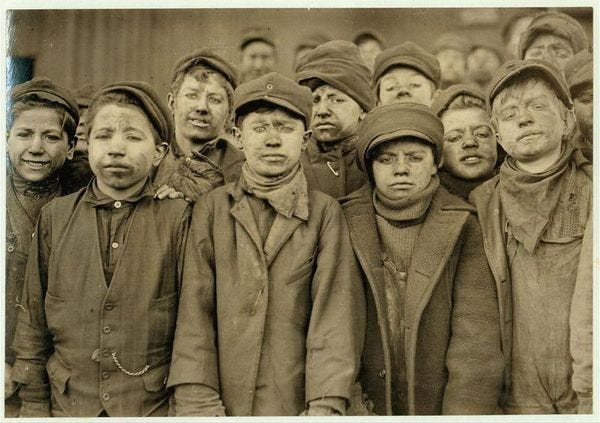

It's worth noting how important the child labor provisions were. Child labor had been the bane of the country for a century. Children were often expected to work through most of American history; they had always worked on farms or in the apprenticeships that defined pre-industrial labor. But in the factory system, children were employed explicitly to undermine worker wages and increase corporate profits. Organized labor and reformers had fought to end child labor for decades, with industries such as apparel and timber leading the opposition to it. This largely, although not entirely, ended with the FLSA, to the benefit of every American.

Yes, There Were Ugly Compromises

There were unfortunate exceptions to the Fair Labor Standards Act. Most notably, agriculture received an exemption, part of its long-term exploitative labor methods. The price southern politicians demanded for passing this bill was to exclude the types of labor that Black southerners did, especially agriculture. A racist America became more racist, even as the overall impact of the bill was hugely positive. Moreover, there was no way for Roosevelt to get this bill through Congress otherwise. It was either a compromise or nothing. Other groups still largely excluded include circus employees, babysitters, journalists, and personal companions.

The agricultural exemption is the most damaging. Farmworkers remain among the most exploited labor in the United States today. The federal government still has no child age limit on farm work, and only 33 states have created one. Most of the states that exempt farm work from child labor laws are in the South, but among the other states is Rhode Island. Those state laws are limited, as state regulation often is. Washington for instance allows children as young as 12 to pick berries, cucumbers, spinach, and other groups when school is not in session. Workers under the age of 16 are prohibited from hazardous jobs on farms, but who is checking that? Not enough inspectors, that's for sure. Farmworkers under the age of 20 only receive $4.25 an hour for the first 90 days of their work. In short, there are still huge gaps in FLSA coverage and in today's political climate, they are more likely to grow, not shrink.

The Fair Labor Standards Act was significantly expanded over the years. Each increase in the minimum wage is an amendment to the FLSA. In 1949, Harry Truman expanded its reach to airline and cannery workers. JFK expanded it to retail and service employees. The 1963 Equal Pay Act expanded its reach to require equal pay for equal work for women and men.

The Fair Labor Standards Act was the last major piece of New Deal legislation. FDR was facing a backlash from the court-packing incident and the alliance of southern Democrats and Republicans determined to limit the power of the liberal state. After the 1938 elections, FDR's ability to create groundbreaking programs declined significantly and then World War II came to dominate American political life.

Why It Matters

The Fair Labor Standards Act created the system of modern work today. Business has eroded it. But child labor mostly still remains banned. The minimum wage is way too low, but it still exists. Overtime pay is a still a thing.

On the other hand, the government has not passed a comprehensive labor law bill that helped workers in 83 years! It has passed a few bills that helped around the edges. And it has passed anti-labor bills such as the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. But it's been a full lifetime since the government really stepped in to even the playing field for workers with their employers.

Of course, if Joe Manchin and Krysten Sinema would dump the filibuster, that could change very quickly. The PRO Act, a major priority of President Biden, would provide just that comprehensive labor law we so desperately need. As I wrote in the New York Times in April, the PRO Act would make much of what Amazon did to stop the unionization of its Alabama facility illegal. It would allow workers to have a real choice whether they want a union, without employer intimidation. In short, it would reset the playing field between workers and companies.

We need more than just the PRO Act. A $15 national minimum wage must be another priority. But any law would help. Whenever you go over 80 years without addressing a situation, it is going to have some pretty bad consequences. Today, that's the massive inequality that helps define life in the twenty-first century.

Further Reading:

G. William Domhoff and Michael J. Webber, Class and Power in the New Deal: Corporate Moderates, Southern Democrats, and the Liberal-Labor Coalition

Jason Scott Smith, A Concise History of the New Deal

Eric Rauchway, Why the New Deal Matters

Want to do some summer reading and help out Yr Wonkette? A portion of each purchase with the links above will help us keep bringing you history! Also fart jokes, as applicable.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

I just checked and wonkette wrote a cookie 18 minutes ago, sigh

You can’t change your looks. You can change the way you dress.