When Congress Almost Did Well By The Newly Freed Enslaved People!

March 3, 1865, in labor history!

On March 3, 1865, Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau to adjudicate relations between white planters and the now-freed slaves in the South, especially around labor issues. A potentially excellent idea, the Freedmen’s Bureau ran ashore on the rocks of a number of 19th century problems, including a lack of funding, that many of the appointees were political hacks, and the racism of many of the officials involved.

The first thing to remember about slavery is that it was a labor system. That’s the reason it existed. We often downplay this because we talk about the racism of the system. This is of course true. In Jim Crow America, the role of labor in American racism took a more secondary status, though it was certainly always there. But with slavery, the entire point was to have a permanent labor force that you did not have to pay and could do with what you would. That it was a racialized labor force was even better because then planters and elites could tear apart any potential alliances between poor workers across racial boundaries by using the power of white supremacy. After all, it’s true enough that many Confederate soldiers didn’t own slaves, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t want to own slaves. Owning slaves was a sign of status and the way one rose in southern society. Controlling the labor of others was, again, the point of slavery.

So, the Civil War ended and the nation quickly moved to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment that ended slavery, except in prison situations — which whites quickly exploited to place a sizable percentage of the Black population back into servitude. But even outside of that, the question of what to do with the four million freed slaves was an open one. Even abolitionist whites weren’t real sure how to handle to this. Should they be allowed to get their own land and live the subsistence economy away from whites they preferred? Should they be strongly encouraged to work on cotton plantations for whites, just with wages? Should the principle of private property be the dominant factor in all decisions once official slavery ended? These were open questions in the North.

Moreover, the South didn’t just acquiesce at the end of the war. They might have lost but that wouldn’t stop them from killing their ex-slaves if they couldn’t get work out of them. The immediate resistance of the South to returning to American governance, exacerbated by the horrible new president, Andrew Johnson, finally forced Congress to do something about this. Luckily, they already had a tool, though one that was pretty half-thought out. That was the Freedmen’s Bureau.

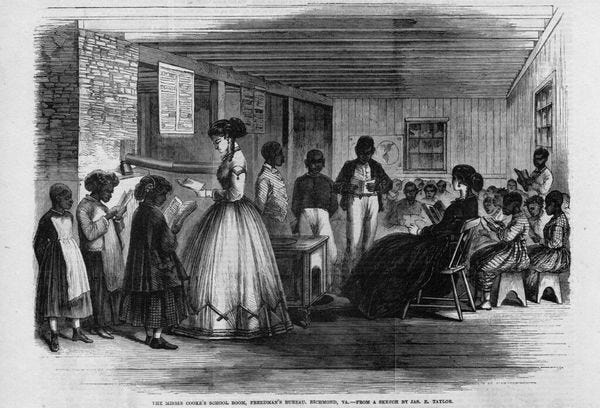

The official name was the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. It had a number of functions in addition to adjudicating labor issues. It also facilitated education programs, where many northern female teachers came to the South to teach literacy and constitutional rights and other key things people needed to know. It also distributed food and medicine, which the freed slaves desperately needed. Its head was O.O. Howard , who was a good sort, about as good as one could have expected to head an agency like this. Howard University is named after him and he was president of it from 1869-74. So at least the head of it was a real abolitionist.

At its best, the Freedmen’s Bureau could solve problems. But there were certainly cases where the freedpeople found the Bureau helpful. In Georgia, its agents did a lot to enforce labor contracts and ensure Black laborers got paid. In Alabama, where a drought compounded conditions at the end of the war, Bureau agents did a lot to keep people alive.

But the Freedmen’s Bureau was rarely at its best. It had many problems. For one, the government was highly unsure about funding, well, anything at all. Even among Republicans, the post-Civil War response was to combine demands for enforcement of civil rights with brutal budget slashing to reduce the size of the government back to something like pre-war levels. To say the least, this was counterproductive and yet the budget-cutting mania was very real, including among abolitionists. What this also meant is that there weren’t nearly enough officers out in the field. What could even the best agent do when he had to cover hundreds of square miles filled with angry, murderous slaveholders killing or whipping now ex-slaves who didn’t go back into the fields?

Second, the quality of Bureau agents varied extremely widely. Some were pretty strong abolitionists who acted in concert with freedpeople’s needs. Others were … sympathetic to slaveowners! But how you got this position was like just about everything in the 19th century – you had the right connections. The inability to professionalize this or have some sort of ideological test probably doomed this entire enterprise.

Third, the entire Democratic Party despised the entire idea of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Remember that even without the South in the nation, Lincoln nearly lost to George McClellan in 1864. The Democratic Party was still arguably the dominant party among whites in the entire nation. So you had frothing Democrats, skeptical conservative Republicans, and abolitionists who were with them on budget-cutting at the very least. There was almost no way the Freedmen’s Bureau could succeed.

In the end, the overreaching of Johnson, vetoing the extension of the Bureau in 1866, and the ex-Confederates sending traitors back to Congress forced the government to respond with troops — which did bolster the Freedmen’s Bureau for awhile. But even here, many Republicans felt that with slavery over, they needed to do nothing more for freedmen. If there were rights to protect, they were voting, not labor.

Actual Black demands over labor were completely ignored. Many Republicans began to invest in southern plantations, seeing economic opportunities by paying Black laborers tiny amounts of money to do what they did before the war. Eventually, sharecropping became the compromise labor measure that gave Black farmers a tiny bit of freedom in exchange for debt peonage and the threat of violence. Almost the entirety of northern whites accepted this without comment, question, or outrage. The Freedmen’s Bureau was shut down entirely in 1872, having accomplished relatively little.

In conclusion, in a different nation, with less racism, less commitment to landownership property for whites, and a willingness to have a more activist federal government, the Freedmen’s Bureau might have worked. Alas, we didn’t live in that America. And really, we still don’t.

FURTHER READING

Heather Cox Richardson, West from Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America after the Civil War

Julie Saville, The Work of Reconstruction: From Slave to Wage Laborer in South Carolina, 1860-1870

Bruce Baker and Brian Kelly, eds., After Slavery: Race, Labor, and Citizenship in the Reconstruction South

Paul A. Cimbala, Under the Guardianship of the Nation: The Freedmen’s Bureau and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865-1870

Please keep Wonkette paying our writers, if you are able!

Yes, and WHY??!?

As Pete Seegar sang:If we could consider each otherA neighbor, a friend, or a brotherIt could be a wonderful, wonderful world