When The Laundry Women Went Out On Strike: This Day in Labor History, February 23, 1864

Don't forget: women were in the labor movement from the very beginning.

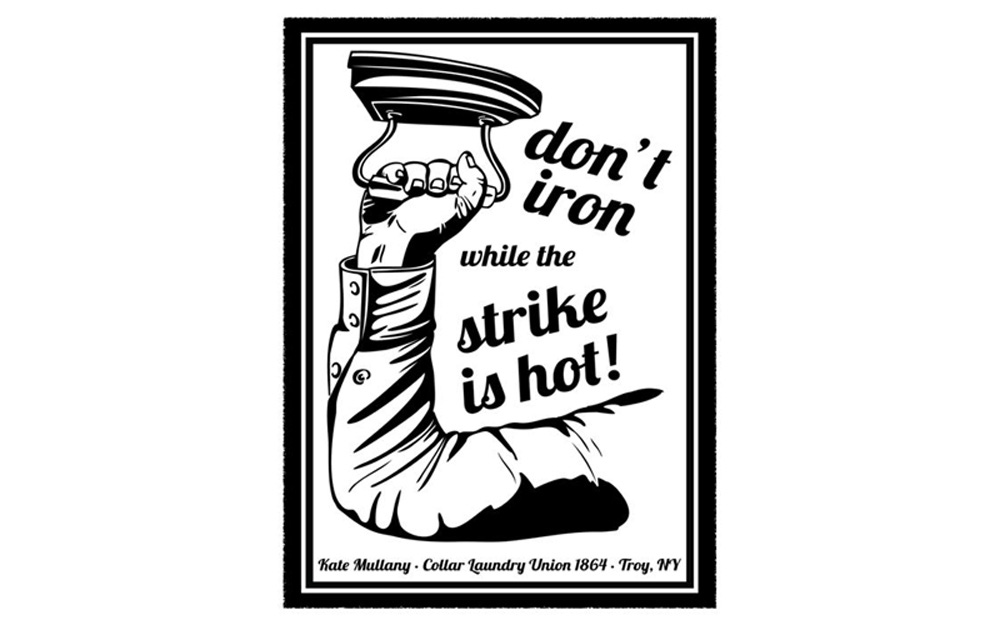

On February 23, 1864, Kate Mullaney (sometimes spelled Mullany), leader of the Collar Laundry Union, the second all-female union in the United States (the Lowell Female Reform Association, established in 1845, was the first), led union members in Troy, New York, out on strike. The CLU wanted higher wages and better working conditions. The strike succeeded, marking a rare union victory for women workers during the era.

Women working in commercial laundries faced the terrible working conditions that were becoming so common as the nation industrialized in the mid-19th century. They worked 12-14 hour days in extraordinarily hot workplaces. The Collar Laundry Union workers labored specifically with collars. This required the use of harsh, caustic chemicals and boiling water. Workers frequently suffered severe burns. Like with the rest of American work in the second half of the 19th century, rapid technological advancements came at the price of worker safety. In this case, it was new starching machines that were known for causing horrific burns for workers. Of course, companies were not held responsible for workers getting hurt or dying on the job. The pay for this labor: $3 a week.

Kate Mullaney was an Irish immigrant born in 1845, emigrating during her teenage years. Her family ended up in Troy, New York, a growing industrial city that specialized in iron foundries and collar production. Troy was one of the nation’s most prosperous cities at this time. In 1864, about 90 percent of the nation’s detachable collar production (a popular fashion of the time) was located in Troy. In the 1860s, about 3,000 women worked in the Troy collar laundries. Mullaney was forced into the labor force in the early 1860s when her father died; with her mother an invalid, she became the family’s primary breadwinner. Like the vast majority of the collar workers, Mullaney was a young unmarried woman. 92 percent of the Irish collar workers were single, and another 5 percent widows. Generally, the Irish worked in the collar laundries while native-born Protestants labored in collar sewing, as it paid better and was seen as more respectable, not to mention less dangerous. Like much work as well, these jobs tended to be passed through families, as workers got jobs for their younger family members.

It did not take long for Mullaney to become a leader of the collar workers movement to make a better life for themselves. On February 23, 1864, she led about 300 workers out of the job and onto the streets. Within a week, 20 Troy laundries increased workers’ pay over 20 percent and agreed to work on safety issues. The strike made the union a successful operation. The CLU lasted for five years, which may not seem long to us today, but that in an era of nascent labor organizations, that was a pretty long run. In 1866, the CLU again went on strike, forcing employers to raise wages to $14 a week, over four times what workers made just two years earlier.

Under Mullaney’s leadership, the CLU was pretty radical for its time. It donated large sums to striking male unions in a time when that was not so common. In 1868, National Labor Union president William Sylvis appointed Mullaney to the NLU’s national office as assistant secretary and women’s organizer, probably making her the first woman to hold a position in a large national labor union. The NLU was also a Troy-based organization, with Sylvis the head of the Iron Moulders Union that had made that city a strong union town for the era. Sylvis also had long supported the idea of women’s unions and so was quite favorably disposed to the CLU. Mullaney was actually elected second vice president of the union at the 1868 NLU convention but she declined that offer.

In March 1869, the CLU won another strike, but this convinced operators to destroy the union. That May workers again walked off the job. But the owners were starting to follow a strategy that would prove very effective throughout this period at forestalling unionization in the United States–they organized and planned a common strategy against the unions. They pressured smaller operators to hold out against the CLU, began to recruit scab laborers, and worked to control press coverage of the strike in Troy. The workers protested the bad press coverage, but while the Troy Times published a letter by the workers, it refused to endorse their actions. New York City newspapers provided more sympathetic coverage, but that was relatively far away. Perhaps the most effective action was to lock out union members. The owners offered more wage increases to workers, but only if they agreed to leave the union. This proved effective. The strike was lost and the union destroyed.

In its wake, Mullaney and some of the other collar workers formed their own collar manufacturing cooperative, Union Line Collar and Cuff Manufactury. Mullaney became president of that cooperative and, working with friends in the women’s rights movement, sought wealthy investors to fund the enterprise. Alas, the cooperative failed in the wake of both struggles to keep up with the latest technologies and the replacement of cloth collars with paper collars, which led to the slow decline of the entire Troy collar industry, although factories were still active into the 1880s. In 1870, Mullaney dissolved the CLU, which was also suffering after the death of Sylvis and the loss of support from the National Labor Union.

At this point, Mullaney and her fellow workers returned to work for their employers at the May 1869 wage levels, but again, this did not last long because of fashion changes. Mullaney eventually faded from view after 1870. We know she married at some point and that she died in in 1906 in Troy. She ended up remaining poor, being buried in an unmarked grave until the 1990s, when women’s rights and labor rights advocates fought to create a National Historic Landmark to remember Mullaney and the CLU. She was given a proper headstone and her home marked with a plaque.

Collar workers continued to organize, with hundreds joining the Knights of Labor in the 1880s.

WHY IT MATTERS TODAY:

It remains critical to center women’s work in our labor history. So often, the history of working women has not received enough attention. Even today, the kind of nostalgia in our politics for factory jobs has a silent quasi-definition of jobs held by white men who could support their families on a single wage without attending college. But even if those days were better, and I would not say they were, it was women’s work at home that kept those factories going. On top of this, women have long worked outside the home. If the labor movement has had long problems with sexism, well, so has society as a whole. But the more we know about the history of women’s activism on the job, the more we can center women and women’s history in our fights for economic justice today.

FURTHER READING:

Tiffany Wayne, ed., Women’s Rights in the United States: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Events and People

Carole Turbin, Working Women of Collar City: Gender, Class, and Community in Troy, New York, 1864-86

Rosalyn Baxandall and Linda Gordon, eds., America’s Working Women: A Documentary History, 1600 to the Present.

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations! Please subscribe, or if a one-time donation works better for you, we promise not to leave it in our pockets when we do the wash.

Ta, Erik. Solidarity forever.

So much this. I think it's very convenient for nostalgics to remember those days when one man (white, able-bodied) could support a family--but nobody is talking about all the free labor his wife was providing every day, that made it possible. I remember my mom squeezing all the dollars and doing so much work which was never considered "labor".