Wonkette Book Club: America's Strikingly Bloody Labor History

A History of America in Ten Strikes by Erik Loomis, Part 2

Railroad robber baron Jay Gould probably never said, "I can hire one-half the working class to kill the other half" (though he may have said something similar about farmers). The quote may be apocryphal, but it's endured in the popular imagination because it sums up much of American history. The wealthy have never wanted for support in their attempts to keep workers from getting too powerful, often through outright murder. And as Erik Loomis's A History of America in Ten Strikes keeps reminding us, American government at all levels has almost always been happy to side with the robber barons to fight uppity workers. Loomis might almost have called his work a history of America in twenty or thirty massacres -- at least until labor fights became slightly more civilized in the middle of the 20th century -- and even then, only barely.

A quick note before we hop into discussing the book: you're very welcome in the comments (which we don't allow anyway) even if you haven't done the assigned reading. You think everyone who shows up at book clubs to sip wine (OK, or coffee) and yack about books has always done the reading? Pfft -- I took several graduate classes on the first hundred pages of major novels, so by golly I know whereof I speak (in my professional opinion, no one has ever finished a Henry James novel, and you can't convince me otherwise.) So what we are saying is simple: c'mon in and chat and you'll pick up a lot here. And if you have the simoleons, please buy the book, because we'll be finishing up our discussion next week; today, we're hitting Chapters 4-7. Oh yes, and also:

We'll let you know when we DO want you to grovel.

Loomis's history of Americans fighting for some measure of rights and dignity at work builds a few basic themes: the power has almost always been in the hands of the bosses, and they give up that power only reluctantly when workers manage to come together to demand change. If at all, because government at almost every level has been in the pocket of the employers -- either because of outright corruption, or because generally conservative governments have feared change devolving into radicalism and anarchy. (This was a more of a concern back when there were actual anarchists.) Since capital and government were absolutely certain any attempts to curb their own power would result in mob violence and bloody revolution, they felt perfectly justified in using extreme violence to crack down against strikers.

Which is not to say there wasn't violence by labor -- in the 19th century, violence was shockingly common, especially in workplaces where you could be maimed or killed by machinery or mine collapses or any number of fun accidents. Loomis points out early on in the book that over 1,000 laborers died in the construction of the Erie Canal. So yes, workers fought back violently, although they tended to be met with far more death and destruction than they inflicted, and the law almost always let violence by strikebreakers go unpunished while dealing severely with labor agitators. Or even just suspected troublemakers.

The Anthracite Strike and the Progressive State

Things improved somewhat in the Progressive era, as Loomis discusses in Chapter 7, as government made some limited moves to curb the power of the robber barons -- though as Loomis notes,

Progressives largely did not believe in promoting the power of unions and thus did not change the fundamental balance of power between workers and employers.

Instead, Progressive politicians tended to seek an end to unrest -- and the few times they didn't send the militia out to bust heads seemed dangerously radical to the capitalist class. Even Progressive measures like the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act could be used creatively by anti-labor interests to protect large corporations. The US Supreme Court held that a union effort to organize boycotts was an illegal restriction of trade, as if the union were a monopolistic actor.

Everything came down to whether government sided with employers. We're tempted to say " or with unions," but honestly, that seldom happened -- the best workers could usually hope for was that government would simply try to force some sort of balance in negotiations.

Loomis contrasts two 1894 strikes to illustrate: when Pullman railcar builders' pay was cut by a quarter, they walked out, and other unions honored the strike, bringing rail service nearly to a halt. President Grover Cleveland sent in the Army to bust the strike, "using the pretense that it interfered with the delivery of the mail" (And again, the bosses invoked the Antitrust Act against the unions, too). Soldiers fired on strikers, heads got busted, and union organizer Eugene V. Debs went to prison. 13 strikers died and 57 were injured, and the strike was quashed.

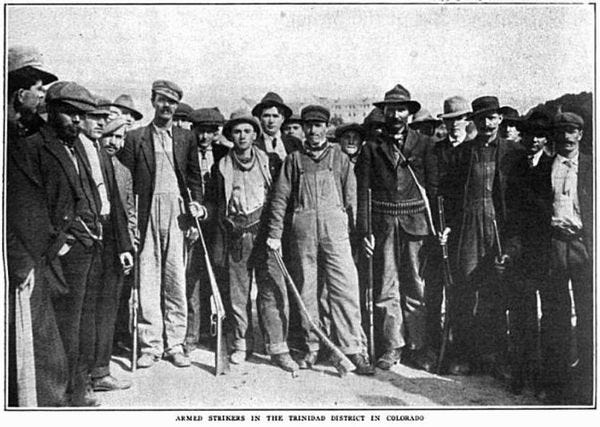

By contrast, a few months prior to the Pullman strike, when Colorado gold miners went on strike over increased work hours with no raise in pay, the mine owners brought in scabs. A group of striking miners near Victor, Colorado beat up six deputies sent to protect the scabs, and the local sheriff asked the governor, Davis Waite, to bring in the militia to "restore order." Instead, Waite refused, so the mine owners raised a private army of goons. Things escalated:

On May 24, miners took over the Strong Mine, near Victor. When 125 deputies marched to take it, the miners blew it up. The deputies fled, but the miners wanted blood. Many of the miners wanted to systematically blow up the mines. They filled a railroad car with dynamite and sent it down the track, hoping to cause an explosion in the deputies' camp, but it derailed.

Strangely, despite the very real violence, Waite didn't send the militia to break up the strike; instead, he send it to keep the two sides apart. The strikers let Waite act as their negotiator, and the owners were forced to restore the eight-hour day and reopen the mines. Not that the owners acquiesced right away, because who ever heard of the government not letting rich guys act as they wanted?

In Cripple Creek, they arrested hundreds of miners, formed a gauntlet, and forced townspeople to run through it while being beaten. Finally, the state militia rounded up the private police force. The governor stated he would keep the militia in Cripple Creek until the owners followed the rule of law, meaning they would have to keep paying their forces to do nothing. The employers caved and the workers won.

Hooray -- for a short while. The mine owners made sure Waite was ousted in the next election, and the concessions won by the miners were soon reversed.

Still, the Cripple Creek strike illustrated that when government doesn't completely side with capital, strikes can work. But when the two are in cahoots, virtually no labor action can succeed.

The chapter focuses on Teddy Roosevelt's intervention in the 1902 coal strike, in which Pennsylvania miners demanded an eight-hour day, union recognition, and a pay system that didn't cheat miners. Needless to say, the owners, led by George Baer, weren't keen on the idea. Baer knew who could best look out for workers, after all, as he explained in a letter he titled "Divine Right of Capital":

The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for -- not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in his infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country.

Loomis notes, "Somehow, the Pennsylvania miners disagreed with sentiment." Eventually, Roosevelt -- after a threat to nationalize the mines -- set up a commission to decide the issue, which came down mostly on the side of the miners, though it didn't give them all they wanted. Especially not recognition of the unions as the miners's sole bargaining agent. All victories seem partial, and far from permanent.

And so on. The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire resulted in reforms, but only after 146 workers died -- mostly women and girls. Even one of the great muckraking works of the Progressive era, Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle, backfired a bit: instead of converting readers to socialism by depicting the awful lives workers faced, Sinclair mostly grossed out his middle-class audience with all the details about the food coming out of packing plants. Instead of labor reform, we got the Pure Food and Drug Act. Says Loomis, "Readers, including Theodore Roosevelt, showed much more concern about themselves than they did the workers making the meat."

(Update: oh, crap, I did that thing where I mixed up Upton Sinclair and Sinclair Lewis again. H.G Orson Welles Fargo, crap)

Then there was the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, when the Colorado National Guard set fire to strikers' tent city, killing four women and 11 children hiding in a basement dug out under a tent. After gunfights between strikers and the militia that killed between 69 and 199 people, Woodrow Wilson sent in the Army -- but like Waite, to enforce neutrality.

Oh, and once again, we have spent too much space on ONE CHAPTER, damn us. Let us proceed in an entirely different style at great expense and at the last minute.

Bread and Roses! Wobblies!

Loomis tackles two main threads (albeit without a stunningly mixed metaphor like THAT) in Chapter 8: 1) The Industrial Workers of the World (aka the Wobblies), which was outright socialist and utopian and far better at grabbing publicity for great big actions than in building long-term union foundations, darn 'em; and B) the 1912 "Bread and Roses" strike by textile mill workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. We are going to rush right through both because we're terrible (yes, this is why we always stole our syllabi from other teachers. Can't plan worth a damn).

Here's the big strength of the IWW: it sought to bring all workers together in "One Big Union" instead of their being fragmented by trade and region, and it successfully organized some general strikes that shut down entire cities. Unfortunately, it had a crappy tendency to not bother building and supporting locals with staying power. The IWW

held consistently to the idea that workers signing contracts with employers would limit their power and accept a state of oppressive capitalism. While perhaps true, this undermined the IWW's ability to build on its own victories because its leaders underestimated the power of employers to win back whatever they might have lost after a brief moment of workers' organizing.

Also, a lot of Wobblies just really couldn't resist the temptation to talk up violent rhetoric about smashing the system and bringing revolution, which gave owners and local governments a handy rhetorical advantage: "[All] employers and the police had to do to convince people of the IWW's danger was to publicize the union's own words."

In Lawrence, the IWW managed some short-term victories, thanks in part to the insane violence of strikebreakers against women and children taking part, and thanks to a fine bit of theater: the effort to send children of striking workers as temporary "refugees" to stay with union sympathizers in other cities.

The children's exodus was masterful propaganda. Newspaper reporters ate it up and it raised desperately needed funds. More children followed, to Boston, Philadelphia, Vermont, New York. Another group of ninety-two children arrived in New York and paraded on Fifth Avenue before going to their temporary homes. In Lawrence, the attention led to more militia violence. The militia harassed, beat, and even bayoneted workers on the street. When a militia member told a man walking a dog to hurry and the owner refused, he stabbed the dog.

The brutal overreactions won attention for the strikers, and eventually, the strikers won a wage increase and rights to overtime -- but damned if instead of staying to solidify the union, the IWW didn't just move on to other actions, including the disastrous Bisbee mine strike in Arizona, which ended with a private army loading strikers and radicals into cattle cars full of cowshit and dumping them in the desert near the Arizona-New Mexico border.

Flint Strike! Meet the Flint Strike!

Chapter 8 brings us the Great Depression, FDR, and finally a government that was, if not pro-labor, at least in favor of something like fairness. Here's Loomis's own takeaway:

Anyone trying to organize a movement today should take three lessons from the workers of the 1930s who made the modern union movement: First, a small group of people can accomplish amazing things. Second, you never know when a small movement will become a mass movement. Third, while protest movements can create mass action, they require legal changes to win. That means electing allies to office. That was crucial in the 1930s.

Needless to say, union gains during the New Deal were also subject to huge compromises that left many workers behind. The 1935 the National Labor Relations Act finally enshrined the right to organize, but to get it passed, Roosevelt had to give in to racist southern Democrats' demands to exclude farmworkers and domestic workers, because darned if white Southerners wanted blacks thinking they had rights. Similarly the 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) didn't apply to agricultural workers or domestics, or to "circus employees, babysitters, journalists, and personal aides."

The 1937 sit-down strikes in Flint, Michigan, were incredibly successful, winning union representation at GM, but again, only after near disaster. Earlier in the '30s, GM spent millions of dollars to infiltrate the workforce with spies, and fired anyone who talked union too openly. The company even hired spies to spy on the spies, lest anyone defect after hearing pro-union talk. The sit-down strike gave workers a tactical advantage against strikebreaking efforts: if nobody walked off the assembly line, GM couldn't bring in scabs.

Again, government action made a huge difference: local government sent armed cops to try to break the strike, but Michigan Gov. Frank Murphy, a New Dealer, sent the National Guard to keep the peace, not to bust heads. Eventually, the strikers won, the UAW was recognized by GM and Chrysler, and unions gathered strength -- but only after resistance from owners. Ford only unionized in 1941 because Henry Ford wanted in on lucrative defense contracts, which were only granted to companies that allowed union organizing. Roosevelt's support of unions wasn't universal -- the government didn't get behind a steel strike in 1937, and it collapsed.

Generally Striking

For the most part, World War Two was good for unions, although they had to agree not to strike during the war years in order to keep worker protections imposed on defense contractors. Those union protections were hated by the employers, who nonetheless accepted them as the price of making assloads of money building war material. It all made for a fairly equitable compromise, although there were still wildcat strikes and some company owners who resented any limits on their freedom to screw over workers. Montgomery Ward CEO Sewell Avery hated Roosevelt and refused to negotiate with striking workers in 1944, but since Ward had a bunch of federal contracts, Roosevelt sent AG Francis Biddle to tell Avery to knock it off.

Biddle told him he was hurting the war effort. Avery responded by saying, "To hell with the government!" Biddle ordered two soldiers to pick Avery up and carry him out of the building. Avery hurled the worst insult he could think of at Biddle, yelling, "You, you New Dealer!" The federal government ran the company off and on until September 1945.

Blacks also got some benefit from the wartime labor crunch. A. Philip Randolph, head of the sleeping car porters' union and future civil rights hero, threatened to lead a march on Washington in the summer of 1941 if the administration didn't end segregation of defense contractors. Roosevelt "desperately wanted to avoid the embarrassment of a nation preparing to fight fascism having its own racial caste system publicized before the world," so he issued an executive order prohibiting discrimination in war industries, and also ended segregation in the federal government. Not exactly out of the goodness of his heart, but he did it.

Following the war, unions engaged in a whole bunch of strikes, winning new concessions but also restoring the old order -- women and minority workers were expected to step aside and let returning white workers take back their factory jobs. Lots and lots of strikes, including, briefly, a general strike in 1946 that shut down most of Oakland, California. Unfortunately divisions within labor doomed it: the strike started with women workers but was soon taken over by men, for the sake of challenging the city's anti-union power structure. For a brief while, it was downright carnivalesque:

All businesses except for pharmacies and food markets, which the workers deemed essential for the city, closed. Bars could stay open but could only serve beer and had to put their jukeboxes outside and allow for their free use. Couples literally danced in the streets.

The unions even kept the city's rabidly anti-union newspapers from being printed. Unfortunately, internal disunity ruined the general strike: Teamsters leader Dave Beck considered the strike leaders communists and forced his drivers to go back to work, despite local Teamsters leaders' support for the strike. Beck engineered his influence to "win" an agreement that didn't even address the demands of the women who'd started the whole thing, and the strike collapsed.

As the Cold War progressed, unions purged any reds who'd been organizers, and thanks to white fears of integration (not to mention commie Jewish unions), the South remained largely untouched by unions, too. Business interests got friendly politicians elected to Congress, and the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act let states enact "right to work" laws, taking entire states out of play for unions. And eventually, union leadership got awfully chummy with the bosses, and before long, it was a lot like the ending of Animal Farm, Animal Farm, yeesh, gross.

NEXT WEEK! LET'S FINISH THIS BOOK!Yr Dok Zoom is gonna figure out how to space out the discussion next time FOR SURE.

There shall be no Nice Things this week, so this is now your open thread!

[ A History of America in Ten Strikesby Erik Loomis. 2018, The New Press. $18.29 in Hardcover / $17.38 Kindle e-book ]

Check out Part One of this Book Club! Also Part Three, too!

Yr Wonkette is supported by reader donations! Please send money to get Dok to his meeting of Ramblers Anonymous. Also, did you buy your own copy of A History of America in Ten Strikes yet? Hurry!

I'm loving Elie Mistal and David Cay Johnston as well.

"0h!!....that's what it's for!"