Wonkette Book Club: Oh F*ck It's Reagan Time

A History of America in Ten Strikes by Erik Loomis, Part 3

Happy Daylight Savings Day, Wonkers! Are you as completely discombobulated as Yr Dok Zoom is, coffee or no? Here's hoping you are not! Nevertheless, let us wrap up our discussion of Erik Loomis's excellent A History of America in Ten Strikes , our Wonkette Book Club selection for this month. It's a hella good overview of labor history in a country that loves to praise hard work, just as long as workers don't get too uppity. Last week we closed with the labor movement at the peak of its power following World War II, when a string of presidents enacted mostly pro-labor policies, or at least tended not to explicitly side with corporate America's desires to gut the power of unions.

Things, as you already know, changed.

How To Strangle A Labor Movement

By the 1970s, Big Labor and Big Bidniss were getting hard to distinguish from each other. George Meany, head of the AFL-CIO, wasn't interested so much in empowering workers as in fighting communism, getting along well with those in power, and making sure contracts with big employers ran smoothly so the union dues kept coming in. And for a lot of Americans, unions appeared to be more aligned with the Establishment than with labor's previous radicalism -- see the 1970 "Hard Had Riot" in which union construction workers gleefully beat antiwar protesters in New York. In 1972, Meany actively opposed the campaign of George McGovern and lied about McGovern's long history of supporting labor -- partly because he thought McGovern was too soft on communism, and partly because he resented post-1968 changes to the Democratic party's nominating process that had reduced Meany's own influence.

Quite a change from earlier in the '60s, when labor leaders had been somewhat more leftish; Loomis reminds us those radical peacenik Students for a Democratic Society drafted their "Port Huron Statement" at a United Auto Workers retreat, and that a lot of early support for SDS came from unions.

Similarly, the full title of Martin Luther King's 1963 March on Washington had been "For Jobs and Freedom," and worker rights had been framed explicitly as part of the civil rights agenda:

United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther spoke in favor of economic justice, the day's only white speaker. The AFL-CIO paid for the buses to get people to Washington, the United Packinghouse Workers subsidized transportation to the march for unemployed workers, and the UAW paid for the sound system that would blast King's speech into history.

Mileage varied, but sadly, a lot of white union workers were far more interested in keeping workplaces segregated than in any of that class solidarity stuff, damn it.

Unionism got tangled up in the late-'60s-early '70s counterculture, too. Younger workers -- a bunch of damn hippies and agitators -- wanted Americans to rethink the meaning of work, in addition to focusing on more typical workplace issues. Some of those troublemakers even thought unions should be democratic somehow. In Lordstown, Ohio, near Youngstown, workers at a Chevrolet plant staged a wildcat strike (meaning it was unapproved by the union) when GM increased the speed of the assembly line for the Chevy Vega, that grotty little economy rustbucket. More jobs were automated on the line, which led to layoffs, too. The grievances were real:

The factory had previously made the Chevrolet Impala at a rate of sixty an hour. The Vega sped off the line at 101 an hour. This gave workers thirty-six seconds to perform eight separate operations.

To make matters worse, GM was intent on making as much profit from the smaller, cheaper Vega as it had from larger cars, and brought in managers who drove the workers as "efficiently" as possible. Big surprise: workers rebelled with slowdowns or working exactly to the rules of the contract, and no more. Some Vegas even ended up on dealer lots missing parts, or having been outright sabotaged.

Lordstown workers walked out in January 1972, but the UAW undercut them, negotiating a return to work for some fired workers but not changing much about the work conditions or the relationship between workers and management.

GM and other American companies kept building shitty cars and blaming the union (as did plenty of Americans), and whoops, Japanese cars started selling really well. A side note: while Loomis frequently highlights racism in labor struggles, he sadly doesn't mention the racist murder of Vincent Chin in 1982. Chin was Chinese-American, but two white auto workers beat him to death because any Asian guy made a handy hate object. "Economic anxiety" wasn't a new excuse for deplorable assholes in 2016.

On top of it all followed the whole deindustrialization / outsourcing / offshoring thing that devastated manufacturing in general and labor in particular, while pumping up corporate profits. Fast forward a few decades: Last week, General Motors shuttered the Lordstown factory for good; the remaining 1,700 workers were laid off.

The last Chevy Cruze rolled off the line Wednesday at the General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio, with employees f… https: //t.co/25V5Rji0kR

— NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt (@NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt) 1551981600.0

But at least GM got a huge tax cut from the Republicans in 2017. It mostly went to stock buybacks, which pumped up share prices a bit.

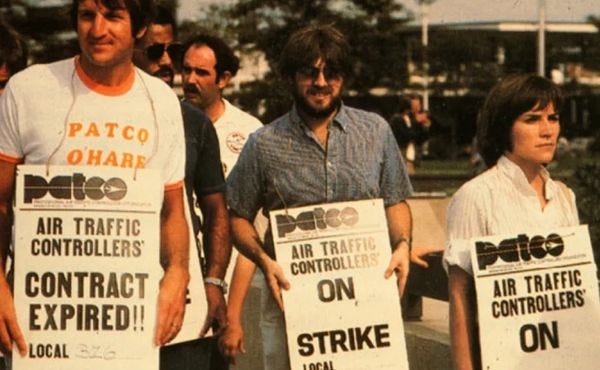

In 1980 Ronald Reagan got elected, initiating a surge of corporate-friendly politics that's lasted through today. The Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) had supported Reagan over Jimmy Carter in 1980, but when air traffic controllers struck -- illegally, yes -- in 1981, Reagan was happy to destroy them, with the full support of the Republicans, free-market fundamentalists, and greedheads who had always seen unions as an unfortunate impediment to getting richer. Welcome to the New Gilded Age, when union busting is just good business.

Again, the air traffic controllers had legitimate grievances -- overwork and incredibly stressful jobs -- but the strike was inconvenient for travelers, and it was easy to portray the strikers as illegal lawbreaking bad guys who wanted to wreck your vacation and the economy. (In a 1978 slowdown, PATCO also had a really boneheaded demand that resurfaced in arguments three years later: they'd asked airlines to provide free international flights for controllers. It was a minor side issue, but made for terrible publicity).

Here's Reagan's presser threatening to fire any controllers who didn't return to work withijn 48 hours. It's still impressively vicious:

Remarks and Q & A with reporters on the Air Traffic Controllers (PATCO) strike www.youtube.com

The controllers badly overplayed their hand: they assumed the government wouldn't dare fire them since they were necessary to keeping planes in the air, but the FAA had been making plans to deal with a work stoppage, and increasing automation meant only about 50 percent of flights were affected. Airlines lost money but supported Reagan. Loomis notes the law forbidding strikes by federal workers didn't require Reagan to fire anyone -- but that was what he decided to do, because after all, they defied the law. The union was decertified, and Reagan blacklisted the controllers from ever holding federal jobs again (Bill Clinton reversed the ban in 1993, but only about 800 of the over 11,000 controllers fired in '81 were rehired).

What Reagan did, in breaking the PATCO strike, was unprecedented. Firing striking workers and hiring scabs in their place had long been a big no-no, and even Nixon, in his day, didn't dare break the (also "illegal") Postal Strike. He crossed a line, he took the unthinkable and made it thinkable, and as a result, unions lost a lot of their ability to effectively bargain.

After that, with companies no longer afraid of a backlash for firing striking workers, it was pretty much open season on unions -- even in fields that couldn't move operations overseas. In Arizona, Phelps Dodge copper provoked a strike in 1983 by offering a truly lousy contract linking wages to the variable price of copper, then closing a major mine for months. The company even had the cooperation of state law enforcement, because it was Arizona and the early '80s. The state formed a special goon squad, the

Arizona Criminal Intelligence Systems Agency (ACISA), a state-funded undercover police force developed only for this strike. Using tactics from the violent days of the early twentieth century, ACISA agents infiltrated the unions, wiretapping about half of the union meetings. The agency shared intelligence information directly with Phelps Dodge officials.

Phelps Dodge even "began smuggling arms into the mine to prepare for an armed struggle." Hello 1880, but no need for Pinkertons when you have the National Damn Guard:

On August 8, about one thousand strikers and supporters surrounded the mine entrance, chasing away the strikebreakers and forcing others to remain inside the mill. In response, the state provided an army to end strikers' resistance. In what was referred to as Operation Copper Nugget, 426 state troopers and 325 National Guard members, assisted by helicopters, tanks, and military vehicles, retook the entrance to the mines.

The strike ended shortly after that, and in 1984, miners voted to reopen the mine without a union. Other companies followed suit.

Loomis notes that while unions may have had some ineffective, disorganized leadership in recent decades, the structural changes in the economy did much of the heavy lifting when it came to weakening labor. But far more important was the collusion of government with corporate power:

[It's] far from clear that even the best leadership could have overcome such a merciless war from Washington and from multinational corporations.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Loomis closes with a discussion of the "Justice for Janitors" strikes of the late 1980s and early 1990s, in which the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) began organizing new types of workers: the mostly minority and immigrant workers who filled jobs with the private contractors hired to clean office buildings. Corporations no longer hired their own custodial staff, so SEIU went after the big contractors. Those contractors often depressed wages by hiring undocumented immigrants. As a result, pay for custodians dropped precipitously:

In 1983, the average wage for a janitor in Los Angeles surpassed $12 including benefits. By 1986, with companies having escaped most of the union contracts, janitors' wages had plummeted to $4.50 an hour, and their benefits had disappeared.

The companies assumed immigrant workers wouldn't cause trouble, fearing they'd be deported, but at the time at least, la migra wasn't all that interested in raiding workplaces where only a few immigrants could be scooped up for deportation. And the increasing number of migrants who'd fled US sponsored wars in Central America weren't necessarily afraid of getting fired, either:

One organizer noted the Salvadoran immigrants weren't scared because "there [if] you were in a union they killed you. Here . . . you lost a job at $4.25."

SEIU also had a knack for publicity, like having janitors in Philadelphia, who'd been told to clean toilets with toothbrushes, picket while carrying around a huge toothbrush. Companies renting space in the buildings may not have been impressed, but the damn sure pressured building owners and the maintenance contractors once the wastebaskets stopped being emptied.

The new willingness of government to get brutal again also resulted in some publicity wins for workers, too: In Los Angeles in 1990, police attacked striking janitors for two freaking hours, beating them with batons, after first telling the mostly Latino strikers to disperse -- but only in English. Of the 400 strikers,

Ninety workers were injured, nineteen seriously. One suffered a fractured skull. A pregnant worker named Ana Veliz miscarried her baby.

LA mayor Tom Bradley finally spoke out on the strike, supporting the workers, and the head of SEIU's New York local said that if the contractor didn't settle in Los Angeles, New York janitors would walk out, too. The contractor settled.

Similarly, Loomis looks at the success of the Culinary Union in Las Vegas, which has organized restaurant workers so effectively that it's become among the most powerful political players in Nevada. Hell, a month after Donald Trump was elected, restaurant and hotel workers forced Trump's Las Vegas hotel to accept a union contract.

Of course, with Trump as "president," the government is once again in full anti-labor mode, and corporations have gotten so good at gaming labor laws set up during the New Deal that the rules actually make organizing harder -- just drag out the process long enough and unions can be outwaited. But Loomis sees reason for some hope: New groups of Americans are demanding rights in the new economy, and there sure is a lot of noise being made by people who want to undo the post-Reagan big money control of government. Workers have to get politically active and elect leaders who will take labor seriously, and unions have to welcome all workers -- hell, with the white working class flocking to Trump's nativist bullshit, there's little need for the bosses to work at dividing workers further.

Above all, we all need to be in the fight together:

[Nearly] all of us are workers. Too often today, the media equates worker with blue-collar factory employee. With these jobs increasingly gone, our lives are more defined by service work or office work than by factory labor. Nearly all of us are workers, whether you are an Uber driver (a company that makes money by refusing to classify its drivers as employees, putting the onus of employment on their backs while the company profits), a graduate student, a McDonald's worker, or a bank teller, in addition to those of us who still have jobs in steel mills and auto factories. As in late nineteenth-century movements such as the Knights of Labor, we need a broad definition of worker, building class consciousness among the 99 percent of us against the 1 percent who control us.

Unite, get political, and raise hell, folks. The end.

[ A History of America in Ten Strikesby Erik Loomis. 2018, The New Press. $18.29 in Hardcover / $17.38 Kindle e-book ]

Yr Wonkette is supported by reader donations! Send us money and we'll keep your brain busy! What should we read next? You could tell us in the comments, if only we allowed them here.

Brawndo!

George Lucas edited Dambusters footage in with footage from other WWII movies to create a "mood reel" both to get the dialogue flow right and to show the Special Effects people the kind of action that he wanted in the Death Star attack on Yavin.