It's Not That Funny That You Can't Tell Black People Apart

The issue affects more than just black celebrities

Aretha Franklin's death Thursday had such an impact on us that even FOX News took time out of its jam-packed schedule of promoting white nationalism to acknowledge the Queen of Soul's passing. Unfortunately, the network confused her with the Duchess of R&B Patti LaBelle. Whoops, there it is again. White folks can't tell us apart.

This is not the first such prominent race identification fail. Total Beauty, a Web site whose whole deal is how people look, confused Oscar winner Whoopi Goldberg with other black Oscar winner Oprah Winfrey. Both ladies are kinda famous. Total Beauty was so certain it was talking about Oprah that its tweet even stated, "We had no idea Oprah was tatted!" That's usually your first hint you're possibly thinking of the wrong black person. It's like tagging Barack Obama in a tweet that says, "We had no idea Obama wore Kangol hats and carried a bad motherfucker wallet!" Well, no duh, you've confused the first black president with Samuel L. Jackson. That's the bad motherfucker white folks often mistake for the black guy in The Matrix .

White people reading at home might not know this, but this happens to non-famous black people all the damn time. Years ago, I worked someplace with another person of color named Errol, and many of the white employees had trouble telling us apart. Errol even went to the trouble of having a mustache and dressing entirely differently than I did. We couldn't have coordinated it better, but it still didn't help. I was referred to as Errol at least once a day and vice versa for him.

This phenomenon is called "the other-race effect." Forbes ran a piece on it in 2014 that explored two possible causes behind it.

The first hypothesis goes something like this: we generally spend more time with people of our own race and thus gain " perceptual expertise" for the characteristics of people who look like us. For example, since Caucasians sport wide variability in hair color, they may grow accustomed to differentiating strangers by looking at their hair. On the other hand, black people show more variability in skin tone, so they might instinctively use skin tone to tell others apart.

The second hypothesis states that people think more categorically about members of other races. Basically, we take notice that they're different from us, but tune out less noticeable characteristics. "The problem is not that we can't code the details of cross-race faces--it's that we don't," Daniel Levin, a cognitive psychologist at Kent State University explained to the American Psychological Association .

I would argue that this might be specific to white people or at least black people don't struggle with it as much. If you put a gun to our heads, we could probably distinguish between the assorted blonde women anchors on FOX News. (The gun is just so we'd actually watch FOX long enough to conduct this exercise.) But it'd be hard for us to function in America if we couldn't tell white people apart. We also couldn't fully enjoy most CW programming.

Trump discovers the third-rail of GOP politics: Blonde Fox News anchors. http://t.co/BA3c7eQcRh http://t.co/WnFukO8ohJ

— Rex Hammock (@Rex Hammock) 1439038095.0

One white lady at my former job who probably still thinks I'm Errol would always look mortified when I pointed out that I was in fact Stephen, whom she'd met many times and had bonded with over our mutual love of flavored coffee creamer. She lived in Park Slope, after all, so she felt just terrible about doing something she feared might be seen as racist. The other-race effect isn't maliciously or intentionally racist, but when we shy away from discussing the larger implications, we can enable racist outcomes. My coworker might sit on a jury or even be asked to identify a black suspect. If she saw an "Errol" commit a crime, would she be able to avoid confusing him with a "Stephen" in a police lineup?

Cross-racial identifications have been shown to be particularly unreliable due to "own-race bias," the unintentional tendency of individuals to less accuratelyidentify members of other races. There has been significant research indicating that juries do not understand the science behind eyewitness testimony generally. It is therefore unreasonable to assume that jurors comprehend the sub-factors (such as own-race bias) that affect eyewitness accuracy in specific circumstances. Juries, as a result of their lack of understanding, occasionally rely on faulty testimony, leading to wrongful convictions.

Black people are often stopped by the police for reasons attributable to the other-race effect. The traffic stop that led to Philando Castile's death only happened because he apparently fit the description of someone who was, well, black . The officer claimed Castile looked like a suspect in a robbery because he had "a wide-set nose." Black people generally speaking have wide-set noses, with a few notable Michael Jackson exceptions.

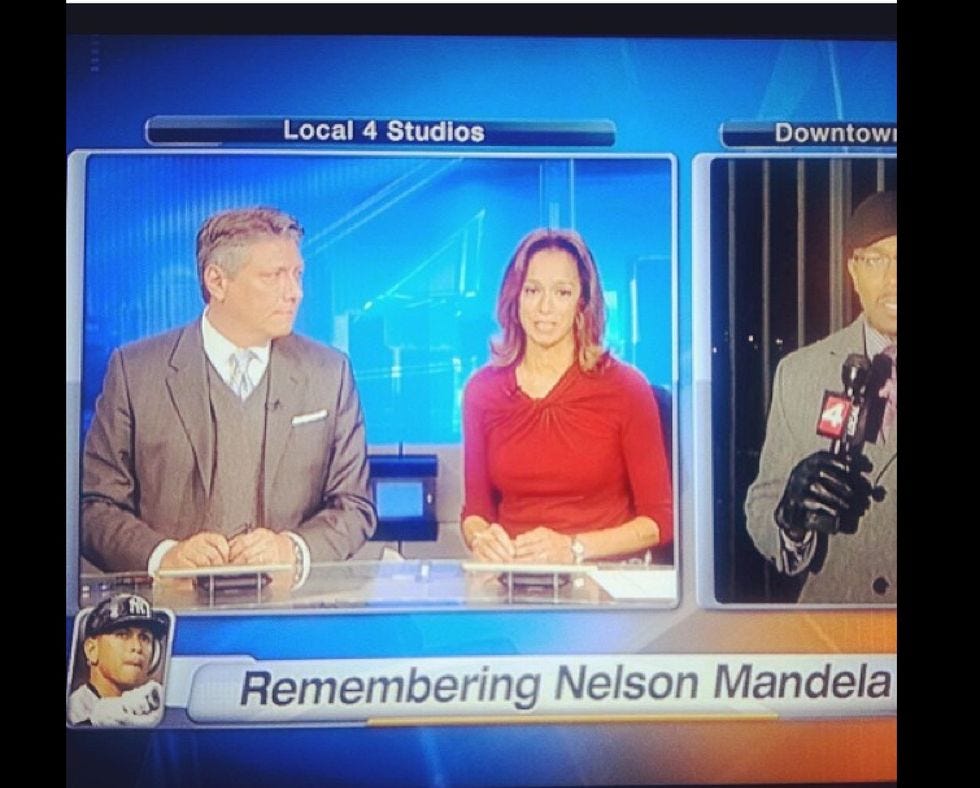

That's not Nelson Mandela Instagram

Fox News sort-of apologized and fell all over itself to come up with a "reasonable explanation" for the "Aretha LaBelle" error. Fox, naturally, would never even admit the other-race effect is even a thing. We'd rather keep it in the embarrassing realm of forgetting the name of someone you hooked up with in college whom you later meet at a friend's wedding. We don't want to have a dialogue about its very real impact on us black people who sang neither "Chain of Fools" nor "Lady Marmalade."

There's a new tip jar in town! Hit it below, to support the ad-free Wonkette experience, or click this link to make it monthly!

it looks like you changed your pic from that golden retreiver dog?

The weird thing is that if I know their dog's name, i'll remember it, but their name? Pfftt. "So, how's Fluffy doing, um, um, Fluffy's mom?"