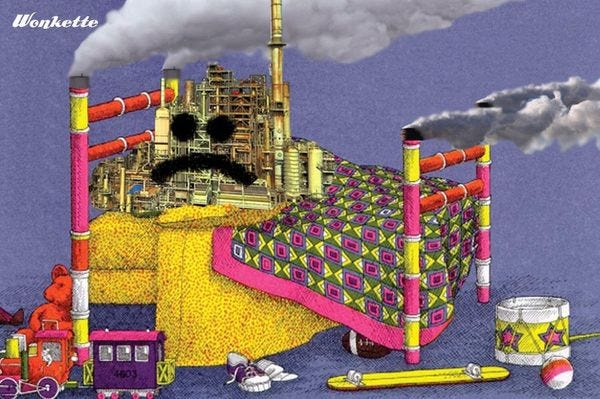

Big Oil's Terrible Horrible No Good Very Bad Day

Pretty good news for life on Earth, though!

Yesterday was a pretty hopeful day for the prospects of getting global carbon emissions under control, thanks to three events that New Yorker climate columnist Bill McKibben is calling possibly the "most cataclysmic day so far for the traditional fossil-fuel industry." These are all big developments that are likely to bring about big changes in three of the world's biggest oil companies.

A Dutch court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to sharply cut its emissions, by 45 percent over the next 10 years, a mandate McKibben says the company can "likely meet only by dramatically changing its business model."

Chevron shareholders voted to require steep cuts in emissions caused by the company's products, which in effect would make the company responsible for emissions from oil and gasoline being used exactly as designed.

At an Exxon Mobil shareholder meeting, members of a climate action investor group won

twothree seats on the company's board of directors, in yet another sign that shareholders of fossil fuel companies want them to take more aggressive action on the climate emergency.

These are all pretty big freakin' deals, and if you want to feel a bit more optimistic about the prospects that humanity might slow global warming to a merely very bad level, instead of a civilization-threatening amount, then go right ahead. As McKibben said in a tweet yesterday, thanking everyone who's fought on climate, "you push long enough and dominoes tumble."

We'd also note that the three actions, though unrelated aside from happening on the same day, came a week after the UN's International Energy Agency warned that construction of new fossil-fuel power generation plants must stop immediately, among other steps needed to prevent the worst effects of planetary warming.

Clean Up Your Shell Game

Since 2015, Royal Dutch Shell has committed to reducing emissions, but not enough for a Dutch district court in the Hague, where Judge Larisa Alwin ordered the company to cut its carbon emissions by 45 percent by 2030, compared to 2019 levels. Reuters points out that

Earlier this year, Shell set out one of the sector's most ambitious climate strategies. It has a target to cut the carbon intensity of its products by at least 6% by 2023, by 20% by 2030, by 45% by 2035 and by 100% by 2050 from 2016 levels.

But the court said that Shell's climate policy was "not concrete and is full of conditions...that's not enough."

The ruling is partly based in European human rights law, which certainly makes us wish Mitt Romney had been right back in 2012 when he called Barack Obama a scary European-style socialist type. If only! The ruling also ordered Shell to make absolute cuts in carbon emissions, as compared to the company's planned targets, which had enough wiggle room to allow, in theory, for actual expansions of emissions. Shell's CEO, Ben van Beurden, said at the company's annual meeting earlier this month that an absolute reduction in emissions would only be possible "by shrinking the business."

Sounds like Shell will have to do that, then, at least if its planned appeal is unsuccessful. McKibben notes that the amount of reductions the court ordered

is very close to what, in 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (I.P.C.C.) said would be required to keep us on a pathway that might limit temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The court also didn't care for Shell's argument that people would be able to adapt to a warming climate, because get out of here with that stuff. The judges acknowledged that Shell believes humans could adopt strategies like using more efficient air conditioning, or managing land and water use to deal with sea level rise. Yes, we can do stuff to deal with some of the effects of the fossil fuels we keep burning, they wrote. But "these strategies do not alter the fact that climate change due to CO2 emissions has serious and irreversible consequences."

The Shareholders Are Revolting! Part One: Chevron

Shareholders at Chevron's annual meeting voted yesterday, by 61 percent, in favor of a proposal to cut back on so-called "Scope 3" emissions, which include emissions in the supply chain, like business travel, transportation of products, investments, and the like. That also includes carbon emissions resulting from the use of a company's products, which for an oil company is a hell of a lot of emissions. (Wonkette's Scope 3 emissions, on the other hand, would include those times that you laugh so hard that you poot.)

Reuters notes that while the proposal

does not require Chevron to set a target of how much it needs to cut emissions or by when, the overwhelming support for it shows growing investor frustration with companies, which, they believe, are not doing enough to tackle climate change. [...]

Oil and gas companies have long argued that they have little control over how their products are used, but with rising investor pressure they are forced to find new ways to cut emissions and fall in line with global climate change pledges.

Damn right they are! While Chevron has pledged to cut carbon emissions, it hasn't set any actual targets to move toward net zero emissions, which it damn well needs to. Such plans are fairly standard in Europe, although some judge may come along and tell a company it needs to be more aggressive.

The Shareholders Are Revolting! Part Two: Exxon Mobil

Meanwhile over at Exxon Mobil, shareholders at the annual meeting rebelled against management's wishes as well, electingtwo update: make that three new board members from an activist investment fund called "Engine No. 1," which owns only a small portion (.02 percent) of the giant company's stock, but which nevertheless rallied enough shareholder support to puttwothree of its four nominees on the board. Engine No. 1 has argued that the company must commit to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, which conveniently is also President Joe Biden's target for the USA to get there as well. It has also argued that for the company to survive, it needs to diversify its holdings, invest heavily in clean energy, and get the hell out of fossil fuels.

The vote was delayed by a one-hour recess, during which Exxon execs no doubt tried to change some shareholders' minds, but nothin' doing.

With the green barbarians now no longer at the gate but actually on the board, the Wall Street Journal reports, Exxon CEO Darren Woods may find his days numbered, despite being reelected yesterday.

Andrew Logan, senior director for oil and gas at Ceres, a nonprofit focused on sustainability that supported Engine No. 1's campaign, said it would be difficult for Mr. Woods to retain his position as CEO after the vote.

"That certainly calls his leadership into question," Mr. Logan said. "There is no going back to the Exxon of old nor should there be."

Let's hope so, given that the Exxon of old — specifically during the 1970s — had been advised by its own scientists that burning fossil fuels would lead to heat being trapped in the atmosphere by CO2. The Exxon of old funded junk science to obfuscate that fact and to delay any action that might result in lower profits. The Exxon of old can't be done away with quickly enough.

UPDATE: Did we say two Engine No. 1 members on the ExxonMobil board?Make that three, after all the votes were counted.

This is all very good news, as McKibben points out:

It's clear that the arguments that many have been making for a decade have sunk in at the highest levels: there is no actual way to evade the inexorable mathematics of climate change. If you want to keep the temperature low enough that civilization will survive, you have to keep coal and oil and gas in the ground. That sounded radical a decade ago . Now it sounds like the law.

Here's hoping that this really does mark a turning point. I might just go out and buy some oil stocks myself, just to be a pain in the ass.

[ Reuters / New Yorker climate newsletter (no paywall) / WSJ / Reuters / Stock News Feed / Update: Reuters ]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please give $5 or $10 a month so we can keep pushing at those dominoes.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

Really? When did they start being that?

So, Yertle, how bloody are YOUR hands?