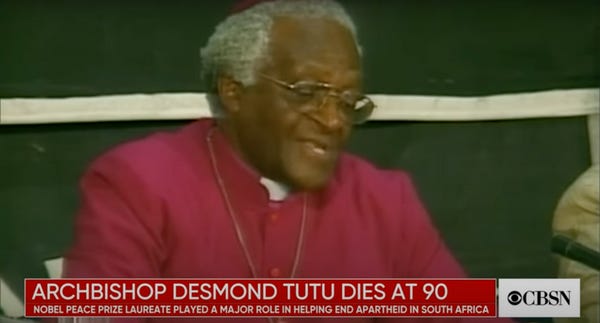

Can We Dare Live Like Desmond Tutu?

Remembering the non-violent freedom fighter.

Desmond M. Tutu, who died Sunday at 90, once said, “Hope is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.” Tutu was born into a brutal apartheid state where the white minority ruthlessly oppressed the Black majority, but he never stopped seeing the light.

He spent his life fighting against apartheid, passionately and non-violently. He was the first Black bishop of Johannesburg, South Africa. Later, as the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, he helped galvanize public opinion globally against racial injustice, not just in South Africa, but everywhere, including the United States.

Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, but was still subject to an invasive body search at a Johannesburg airport in 1986.

From the New York Times:

Perhaps, he mused, his metal pectoral cross had triggered an alarm.

“Did they think it was a weapon?” he [said.]

Archbishop Tutu preached that apartheid dehumanized white oppressors as much as it did the Black people they oppressed. He advocated for economic sanctions against the South African government as a strong weapon for change. He saw little value in Ronald Reagan’s policy of “constructive engagement” with racist South Africa.

“To be impartial,” he said, “is indeed to have taken sides already with the status quo. How are you to remain impartial when the South African authorities evict helpless mothers and children and let them shiver in the winter rain?”

When apartheid ended in the early 1990s, he helped foster a new relationship between white and Black South Africans. He served as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and gathered testimony that documented the viciousness of apartheid. This wasn’t about making white people feel guilty, as Americans conservatives might say. Tutu understood that true healing wasn’t possible unless the still-open wound was first cleansed.

“You are overwhelmed by the extent of evil,” he said, but he stood by the principle of restorative justice. He wasn’t interested in vengeance, but simply a better world. This extended beyond race. His advocacy for human rights included the LGBTQ community. He was a vocal proponent for same-sex marriage even as homosexuality itself was still a crime in 38 African countries. He declared in a 2013 interview:

“I would not worship a God who is homophobic,” he said in 2013, launching a campaign for LGBTQ rights in Cape Town. “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say, ‘Sorry, I would much rather go to the other place.’”

Tutu said he was “as passionate about this campaign as I ever was about apartheid. For me, it is at the same level.” He was one of the most prominent religious leaders to advocate LGBTQ rights — a stance that put him at odds with many in South Africa and across the continent as well as within the Anglican church.

Tutu ordained women priests and promoted gay priests. He was brave and outspoken, never shying from criticizing the new South African government. In 2004, he accused President Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela’s successor, of seeking to enrich the privileged few, while “many, too many, of our people live in grueling, demeaning, dehumanizing poverty.”

"We are sitting on a powder keg … we cannot glibly, on full stomachs, speak about handouts to those who often go to bed hungry. It is cynical in the extreme to speak about handouts when people become very rich at the stroke of a pen. [...]

What is black empowerment when it seems to benefit not the vast majority but a small elite that tends to be recycled?"

Tutu possessed a disarming wit. He was not fond of limousines, and especially police escorts. He sounded not unlike Richard Pryor when he told the Washington Post, “You know, back home, when you hear a police siren, you figure that they are coming to get you ... It still makes me a bit nervous riding with them.”

The archbishop was first diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997. As his health failed, he stopped giving interviews and rarely appeared in public. However, in 2015 he did meet with Prince Harry, who presented him with a honor on Queen Elizabeth’s behalf.

Tutu believed that “as much as the world has an instinct for evil and is a breeding ground for genocide, holocaust, slavery, racism, war, oppression, and injustice, the world has an even greater instinct for goodness, rebirth, mercy, beauty, truth, freedom and love.” Let’s try to prove worth of the archbishop’s optimism.

[ New York Times ]

Follow Stephen Robinson on Twitter.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

Yr Wonkette is 100 percent ad-free and entirely supported by reader donations. That's you! Please click the clickie, if you are able.

Yes there were. And even worse -- the dread Soviets provided diplomatic support and guns to the ANC.

This was known as proletarian internationalism and was considered a good thing by many in the solidarity movements. I was active around Central America in the 80's myself.

Guessing you make shrill unfounded accusations frequently.

So why not hide them, since you can't deal with it?