Environmentalists At The Gates

When greenies and unions joined forces.

On February 15, 1988, environmentalists stormed the gate of International Paper in Jay, Maine, attempting to shut it down as part of a solidarity action with workers on strike. This incident provides more evidence of the possibility for alliances between environmentalists and workers, which we desperately need today.

In the summer of 1987, the mill’s 1,250 union workers, some in United Paperworkers International Union (UPIU) Local 14 and some in International Brotherhood of Firemen and Oilers (IBFW) Local 246, went on strike. They engaged in some big actions to build publicity, including a march of 10,000 people on August 1.

The reason reflected the all-too-common actions of companies in the 1980s, as International Paper decided to follow the example of Hormel, Phelps Dodge , and indeed, the federal government , in breaking the long-term social contract created with workers that had led to good wages and benefits.

In the decades leading up to the 1987 walkout, the unions had not made a huge deal over the company’s many pollution problems, accepting the wages and benefits in return for the company controlling how it operated. But when IP decided to break that social contract with the union, as well as its unions in plants in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania; DePere, Wisconsin; and Mobile, Alabama, workers now felt free to discuss the entirety of how horrible IP actually was. IP demanded huge union givebacks, including an end to Sunday premium pay, the replacement of 350 workers with contracted labor, and the company taking control of many work rules.

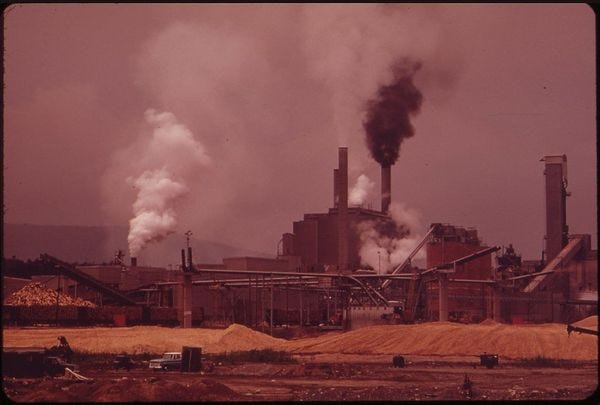

The workers walked out and the company almost immediately replaced them with scabs. UPIU president Wayne Glenn immediately targeted the environmental problems of the mill as a key leverage point, telling reporters the union would point out all the problems and saying “we know where all the skeletons are buried,” which nearly included those of dead union members as several accidents had taken place in the prior months.

The influx of environmentalists coming to help out the strikers stemmed from International Paper’s terrible pollution problems, which affected the local community. Despite Glenn’s rhetoric, in the early months of the strike, the public focus remained on economic issues, even as the union fought with Maine Department of Environmental Protection, trying to get the state to bust the company over its constant and visible pollution into the Androscoggin River.

But environmental issues played a bigger role as time went on, including the union taking three ordinances to the Jay City Council, one of which included the strict enforcement of pollution laws. The unions, especially UPIU, had long publicized the terrible environmental record of IP. Their members felt at risk from the indifference to air and water pollution laws and the congenital workplace safety and health issues the company would not take seriously.

Ultimately though, it was IP’s indifference to the local citizens that made this effective. In late January and early February, IP had three toxic gas leaks. On January 28, a hydrogen sulfide leak led to the hospitalization of eight scabs. A chlorine gas leak sent another seven scabs to the hospital on February 14. That was the final straw for greens.

But the real issue came on February 5, when two scabs made some fundamental safety errors that led to the nozzle of a chemical storage tank breaking off and the release of 144,000 gallons of liquid chlorine dioxide escaping. That could have caused massive fatalities if the winds were blowing the wrong way.

In other words, International Paper’s unwillingness to negotiate with their unions was endangering the lives of not only the scabs replacing them but also of everyone in the local community. UPIU leadership realized that these accidents could help them a lot at the bargaining table by mobilizing community support.

After the toxic gas leaks, the alliance between the union and environmentalists grew rapidly. The union held mass meetings every Wednesday and Cathy Hinds, leader of Maine People Organized to Win Environmental Rights (MPOWER), along with other green leaders urged the workers to get more involved in environmental issues and for environmentalists to help out on labor issues.

When MPOWER and other members charged the International Paper gates on February 15, they were smart about it. They claimed it was a completely independent action, one not created in an alliance with the union. This was smart because it created an entirely different line of attack on IP, one the company could not just say was their crazy workers, not to mention use labor law against the union for it.

The next day, local citizens, rallying under a new group they called Citizens Against Poison (CAP), attended the city’s Board of Selectmen meeting to demand the closure of the mill entirely. Most of these people had relatives who worked in the mill. They also had children they feared IP would poison and kill. They didn’t want the mill permanently shuttered. What they wanted was environmentally responsible stewardship that also treated workers with respect and kept them safe on the job. The local unionists kept up the pressure and it looked like a big victory could be at hand.

Alas, it was not to be. Once International Paper succumbed to this pressure just enough to offer new negotiations, Glenn ended the corporate campaign and the work with environmentalists, which had included local union leaders reaching out to Ralph Nader, who had previously written on environmental issues in the Maine paper industry. The negotiations failed entirely as IP would give up nothing.

With the momentum gone, demoralization set in. The union could not continue to fund the strike. Glenn ordered Local 14 to call off the strike entirely in October 1988. All the workers were replaced by the scabs. The environmental campaign had won its own battles, including a local pollution ordinance in 1988. IP attempted to get it overturned through a 1989 ordinance that used a strategy to blackmail Jay residents over their jobs as the central issue, but a good counter campaign by both the now fired unionists and the greens defeated it. Over the years, that ordinance has led to many fines against the mill, which IP eventually sold but was operational at least until a few years ago.

The relationships between the labor and environmental movement are complicated but they can be built and sustained. In some ways, what happened in Jay was possible because it allowed environmentalists to be environmentalists, doing their own thing in coordination with unions, but ultimately doing their own thing. It also worked because local citizens saw the environment as an issue that affected them, not something that was about polar bears far away. They were motivated by the pollution and suffering and fears they experienced.

It’s highly unfortunate that UPIU leadership kneecapped this movement at its foundation. It makes sense that they wanted to get their workers back in the plant and end this strike as soon as possible. But the naivete in the face of the obvious corporate campaign to destroy unions was deeply damaging. Who knows if a full-scale blue-green alliance in full frontal attack on International Paper would have worked. But it wouldn’t have ended any worse for the workers even if it had not.

WHY IT MATTERS TODAY

Whenever stories about the relationships between the labor and environmental movements hit the news, it’s to highlight the negative. From the spotted owl in the Northwest in the 1980s to the Dakota Access Pipeline a few years ago, they serve a media narrative that these two groups can never get along. Those stories are real enough. But what never gets into the media is the equally long history of the labor and environmental movements working together, as we see here in Jay, Maine.

Today, with climate change becoming the overwhelming issue of our time, we desperately need a strong political alliance between organized labor and greens. Moreover, neither group has the political power they had decades ago. They need each other too. Luckily, in states such as Rhode Island, where I live, in the last few years, a real alliance has developed. A new project to push for green infrastructure built with union labor has made a significant impact on the state Legislature, with laws either passed or in process to push for rebuilding the state’s crumbling schools, creating carbon-free public transportation, the widespread building of offshore wind turbines, and other investments that provide union labor good jobs and move the state toward real sustainability. Other alliances are advancing in states such as New York and Illinois. We need to learn about these as well, in order to build toward greater cooperation between these two movements as we seek to save the planet from destruction.

FURTHER READING

William Brucher, “From the Picket Line to the Playground: Labor, Environmental Activism, and the International Paper Strike in Jay, Maine,” published in Labor History in 2011.

Jay-Livermore Falls Working Class History Project, Pain on Their Faces: Testimonies on the Paper Mill Strike, Jay, Maine, 1987-1988

Julius Getman, The Betrayal of Local 14: Paperworkers, Politics, and Permanent Replacements

Please keep us paying our writers a living wage, if you are able!

Drowning is underrated.

She's channeling the ghost of Erik Loomis. Which is impressive, given that he still lives. As far as we know.