Formerly Incarcerated People Just Want To Be Able To Live And Work Somewhere

And they're looking for 'protected class' status to help them do it.

A group of formerly incarcerated people are agitating to be protected from discrimination by being recognized as a protected class, Truthout reports.

While we've certainly come a little further in recent years as to how we treat people once they leave the criminal justice system — with some states now making it illegal to ask prospective job applicants if they have felony convictions — we have a long way to go. One of the women leading the movement for protected class recognition, Bridgette Simpson, who served 10 years in prison because her abusive ex-fiancé used her car while committing armed robberies and because she bought something with one of the credit cards he stole, says she filled out over 40 rental applications and was turned down each time.

“There aren’t any opportunities, there aren’t any places who are willing to accept people who have served the sentences that they were handed out,” Simpson told Atlanta News First . “I served a 10-year sentence and upon my release, there was nothing for me. I literally had to live underneath a bridge, live in my car, and all of those things but thankfully I was able to pull on my community and they were able to help me get some upward mobility. However, there are a lot of people who can’t.”

This was why Simpson and her former prison roommate Denise Ruben started the organization Barred Business , which seeks to create "a world where justice-impacted people can live, earn, build collective power, advance electorally, and grow economically without discrimination." Specifically, they started campaigning and canvassing in Atlanta, seeking support for an ordinance declaring formerly incarcerated people a protected class.

As the result of their campaign, the Atlanta City Council voted last year to make the formerly incarcerated a protected class and make it illegal to discriminate against them in housing or hiring. This is a pretty big deal, and one that affects one in eight Georgians. Just to be clear, however, the Fair Housing Act does not generally apply to roommate situations, so it would not mean that anyone has to rent a room in their personal home or apartment to a person with a history of violence.

Americans have a very hard time believing that people who have committed crimes are not just going to go and commit them again. This is at least partly because we admittedly have a retributive justice system based in punishment rather than a distributive justice system based in rehabilitation. Perhaps if we focused more on the rehabilitation, people might be able to trust more that those who are let out of prison are not a danger to them.

That being said, it seems fairly obvious that depriving people of the ability to live somewhere and have a job is not something that will end well. It is hard, frankly, to describe a scenario in which that does work out well for everyone involved.

"A person might not want to steal, a person might not want to sell drugs or rob, but if you need to steal to eat, and your stomach is talking to you, you’re more likely to steal to eat, and that’s known,” William Freeman, a formerly incarcerated organizer and president of Redistribute Agency and Wealth (RAW) Trust told Truthout. “And so it’s also known where we can live at, and where we can’t live, so the outcome of that is hyper-police activity in areas, right? It’s a manufacturing of crime. It’s a manufacturing of disenfranchisement, homelessness, and all these other things, and then they collect us in these areas.… And if one person gets something to eat, and everybody’s not eaten, now that escalates into some first-degree assault, murder, robbery, kidnapping. It’s the systems put in place around the community that have us moving like that.”

Simpson, Ruben, and Freeman, who is based in Baltimore, have since been working together on model legislation to make formerly incarcerated people a protected class in other cities and states. As much as that term "protected class" may get people's hackles up because you know someone's gonna go "Oh, so now felons are better than me?" it is something that will make us all safer.

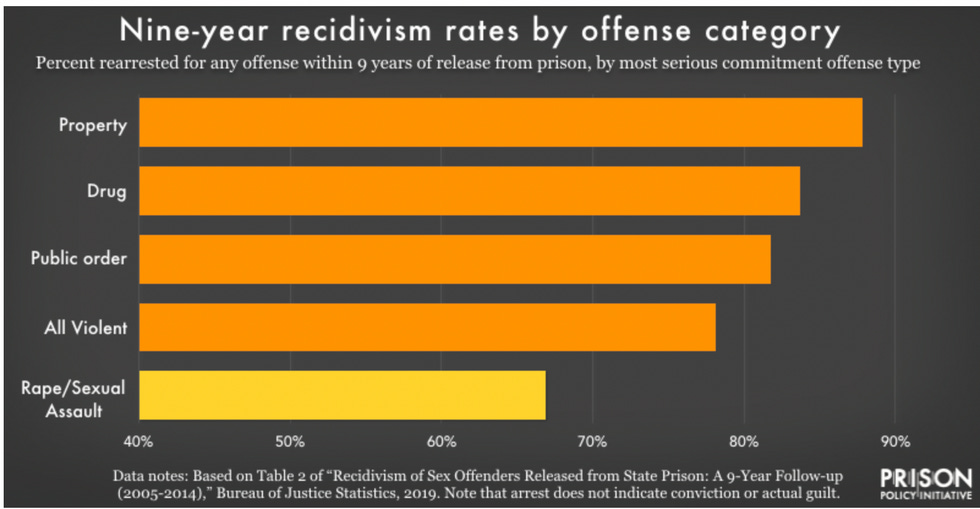

Since it's a concern I really do understand, I'm going to point out here that sex offenders actually have the lowest rates of recidivism , and there are already laws regulating where they can live and work (though these need some looking at as well, because maybe they shouldn't apply to people who got caught having sex on the beach or peeing in public, or result in people having to live under a bridge ). If you notice, many of the crimes for which there are very high recidivism rates — specifically property, drug, public order — are those that could likely be exacerbated by not being able to get a regular job or a home.

This is a problem the Biden administration is looking into addressing as well. In April of last year, HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge instructed staffers to review programs and policies that might "pose barriers to housing for persons with criminal histories or their families," and federal laws that keep those with criminal histories from "accessing publicly funded housingprograms."

We are a nation that loves retributive justice. A nation that loves "scared straight" programs whether they work or not ( studies show they actually make it more likely that teenagers will commit crimes); that loves the idea of sending "troubled" teens to boot camps (which are also more likely to increase recidivism); that loves the sayings "Don't do the crime if you don't wanna do the time" and "It's prison. It's supposedto be bad" almost as much as it loves the saying "Don't drop the soap!" (because sure, punishing criminals with rape is very constitutional); that gets outraged about the idea of "Club Fed" ; and that believes very deeply in the idea that the only way people will ever change is if they hit rock bottom (alsonot actually very helpful ).

We can look at our prison system and high rates of recidivism and look at Norway's, with its relatively pleasant conditions, low sentences, and very low recidivism rates and still want to do things "our way." Because it feels good. To some people anyway.

This is all to say that it would be extremely difficult for Americans to accept something like this, regardless of the results it produces. It is human nature, frankly, to choose what feels right over what is actually effective. It is very easy to say that people who committed crimes deserve to be rejected from housing and jobs as part of their punishment, or to say that people ought to have the right to keep those people out of their apartments and employ. That's even understandable. But in the meantime, you just can't have people out there with no ability to get work or housing, so something has to be figured out. We can keep people incarcerated forever or we can figure out some way to allow them to exist on the outside when they are released, but this midpoint where we let people out into a world where they can't work or live anywhere is simply not tenable and is only going to result in more crime.

Wonkette is independent and fully funded by readers like you. Click below to tip us!

I'm afraid when you tell a republican to "look at Norway" all they see is white people. Then they say stupid shit like, well, we have special challenges because of our, ehem, racial divide.

You must keep punishing people for their transgressions, it's in the Bible.

The Old Testament parts, not that wussy Jesus-endorsed forgiveness stuff.