Happy Labor Day! Let's Talk About Some Awesome Ladies Of The Labor Movement

Because it was not actually just a bunch of flannel-wearing white dudes.

A version of this article was initially published on May 1, 2019. Happy Labor Day, we’re taking the day off!

When we talk about the history of feminism, we tend to think about the causes and struggles of middle class white women. When we talk about labor history, we tend to think about the causes and struggles of white working class men.

And that is some absolute bullshit.

Working class women, very often women of color and immigrant women, were, are and always have been the backbone of the labor movement. They were working and organizing well before Second Wave Feminism "made it possible" for women to enter the workforce. They're the ones who first fought for equal pay, and they're the ones who were doing the bulk of feminist work and activism during the years in between getting the right to vote and The Feminine Mystique. They are still fighting today.

So, since it's Labor Day, let's celebrate the hell out of them, starting with the woman who started it all.

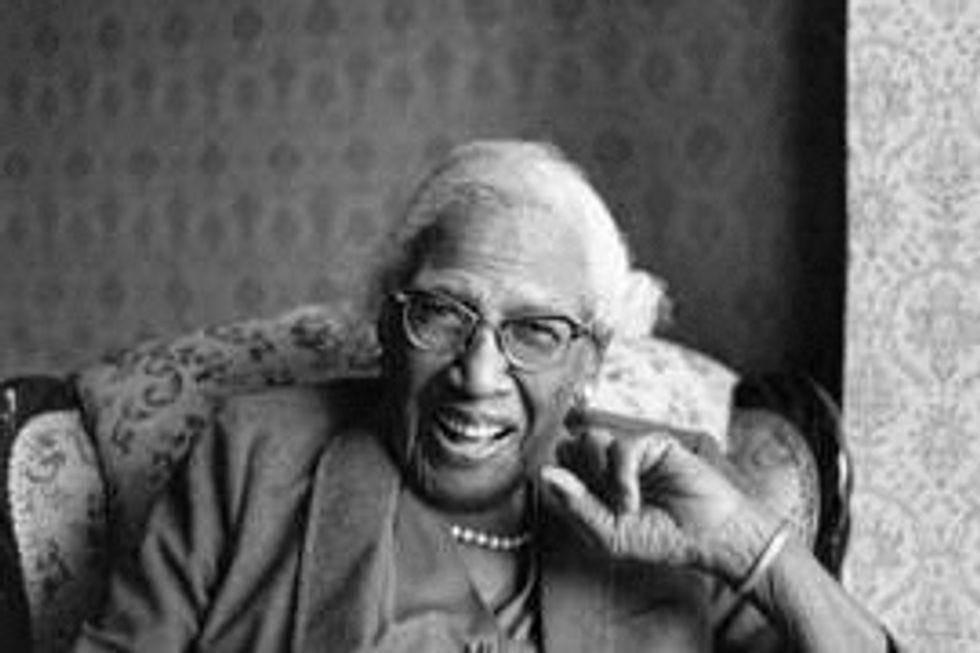

Lucy Parsons

"More dangerous than a thousand rioters," anarchist Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was a writer, orator, one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World, and tireless campaigner for the rights of people of color, all women, and all workers. Her husband, Albert Parsons, was one of the Haymarket martyrs.

We, the women of this country, have no ballot even if we wished to use it ... but we have our labor. We are exploited more ruthlessly than men. Wherever wages are to be reduced, the capitalist class uses women to reduce them, and if there is anything that you men should do in the future, it is to organize the women.

Though Parsons and Emma Goldman were widely regarded as the most prominent female anarchists of the day, they very notably did not get along so well. Parsons believed that oppression based on gender and race was a function of capitalism and would be eliminated when capitalism was eliminated, whereas Goldman believed such oppression was inherent in all things. Parsons was all class struggle all the time, and felt that the "intellectual anarchists" like Goldman spent too much time bothering with appealing to the middle class.

One of her most important contributions to the labor movement was the concept of factory takeovers.

"My conception of the strike of the future is not to strike and go out and starve, but to strike and remain in, and take possession of the necessary property of production."

Parsons is best known for being the woman who really started the celebration of May Day as a day for workers' rights — leading a parade to commemorate the anniversary of the Haymarket Affair. Soon, nearly every other country in the world followed suit and proclaimed this day International Worker's Day. Alas, here in America, we go with the less radical and more picnic-y Labor Day that we are celebrating today, because Grover Cleveland thought a federal holiday commemorating the Haymarket Affair would encourage people to become anarchists and socialists, and no thank you, he did not want that.

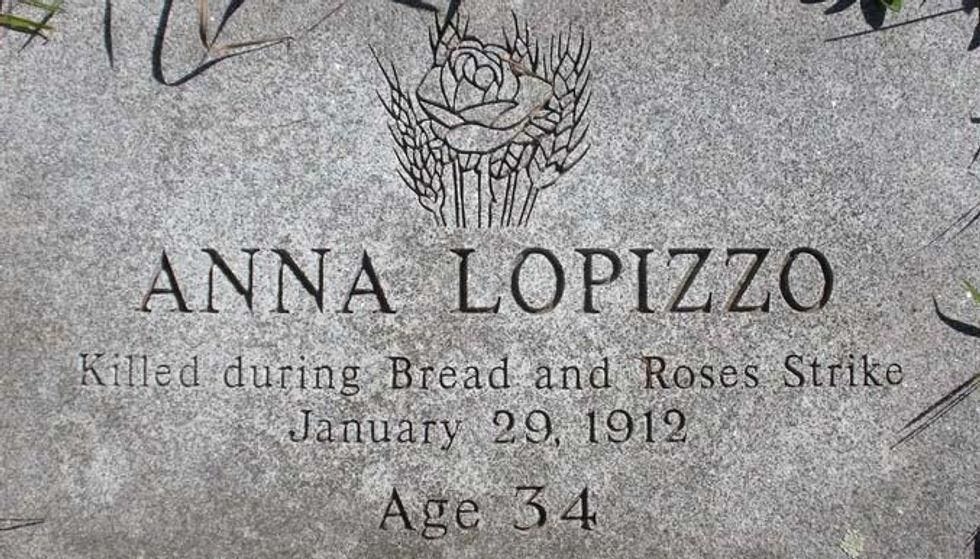

Anna LoPizzo

Not much is known about Anna LoPizzo, other than that she was a 34-year-old mill worker who was murdered by police officer Oscar Benoit during the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike — also known as the Bread and Roses Strike. Initially, police tried to charge two IWW organizers who were miles away for her murder, even though literally everyone there had seen Benoit shoot her.

The reason for the strike in the first place was that the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, cut worker pay after the state cut the number of hours women could legally work from 56 down to 54. The Industrial Workers of the World, led by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (we'll get to her in a minute), organized more than 20,000 workers of more than 40 different nationalities to demand they get their fair wages. One of the primary tactics used in the strike was sending the starving families of the mill workers on a tour to New York City so that people there could see for themselves what these low wages were doing to children. Between that and LoPizzo's death, sympathy was on the side of the workers. Congressional hearings into the conditions of the mills were held, and the mills themselves ended up settling the strike by giving all workers across New England a 20 percent raise.

Lillian Wald

Susan B. Anthony isn't the only important feminist buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery in my hometown of Rochester, New York. There is another. Her name was Lillian Wald, and she was a total fucking bad ass. She wasn't just a suffragist — she was also an early advocate for healthcare for all people regardless of economic class or citizenship, a founding member of the NAACP, lobbied against child labor, advocated for the rights of immigrants, helped to found the Women's Trade Union League, and was an anti-war activist. Wald also founded the Henry Street Settlement House in New York City, which provides — to this day — social services, education, and health care to the impoverished. And she was active in the ACLU.

WHY THE HELL IS SHE NOT MORE FAMOUS? I am legitimately bothered by this and bring it up often.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Hey! You know who was super freaking awesome? Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. As previously mentioned, she was an organizer with Industrial Workers of the World who helped organize the Lawrence Textile Strike. She also organized a hell of a lot of other strikes across the country, helped found the ACLU, and was known for the creative tactics she used to elicit sympathy and support for the American worker.

Hattie Canty

When Hattie Canty's husband died in 1972, she found herself supporting eight children on her own. She found work as a maid at a Las Vegas hotel where she joined the Las Vegas Hotel and Culinary Workers Union Local 226. By 1990, she was president of that union, leading one of the longest strikes in American history — a six year strike of hospitality workers which, happily, ended in victory.

The Women of The Atlanta Washerwomen's Strike

Back in the 1880s, only two decades after the Civil War ended, the most common occupation for Black women was as laundresses — this was largely because if poor white families were going to hire anyone to do chores for them at all, they were going to hire someone to do their laundry. These women were independent workers, often working from their own homes and making their own soap, and they only made about $4 a month. (Average non-Black-woman laborers earned about $35 a month in 1880.)

One day in 1881, about 20 of them got together and decided that $4 a month was some bullshit for all the work they were doing and decided to go on strike and demand wages of $1 for every 12 pounds of washing. Three weeks later, 3,000 other women joined them. Unsurprisingly, the city freaked out. They fined any participants $25 — which was a lot of money when you only made $4 a month — and they offered tax breaks to any corporation that would come down there to start a commercial steam cleaning business. Still, the women did not back down.

Eventually, people got really sick of doing their own laundry, and the city decided to back down on the fines, and accede to their demands for fear that the unrest would spread to other industries.

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta, along with Cesar Chavez, helped to organize the National Farmworkers Association, which later became United Farm Workers. She wasn't a farmworker herself — rather, she was an elementary school teacher who was tired of seeing the children she taught living in poverty because their parents were not making enough money as farmworkers.

I couldn't tolerate seeing kids come to class hungry and needing shoes. I thought I could do more by organizing farm workers than by trying to teach their hungry children.

Together with Chavez, Huerta organized the successful Delano Grape Strike (or as your mom calls it, "that time we couldn't eat grapes for five years" or as Rebecca's mom calls it "serious people don't care if a boycott 'ends'"), which led to better wages and working conditions for farmworkers, and she has continued working as an activist and an organizer ever since.

Angela Bambace

Though she's not as well known as some of the other women on here, Angela Bambace, an organizer for the International Ladies Garment Worker's Union who started unionizing her fellow shirtwaist factory workers at age 18, is a personal hero of mine, along with her sister Maria. Angela was known to punch strikebreakers in the nose, which was pretty freaking badass.

She also left her husband and a traditional marriage in which she was confined to "making tomato sauce and homemade gnocchi" — and lost her parental rights in doing so, because back then, women didn't have any — to fight for workers' rights on the front lines. She was the first woman woman elected Vice-President of the ILGWU, which previously only had male leadership, where she worked from 1936 until 1972.

May Chen

May Chen, also of the International Ladies Garment Worker's Union, led the New York Chinatown strike of 1982 — 20,000 workers strong and one of the largest strikes in American history. As a result of the strike, employers cut back on wage cuts, gave workers time off for holidays and hired bilingual interpreters in order to accommodate the needs of immigrant workers.

Lucy Randolph Mason

Lucy Randolph Mason was an interesting one. She was a well-off Southern lady from Virginia, related to George Mason (author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights), Supreme Court Justice John Marshall, and, uh, Robert E. Lee. So, you know, you might have an idea in your head about what her deal might be. And you would be so wrong.

So, despite being from this very fancy family, Lucy goes and gets a job as a secretary for the YWCA at 20. In 1918, she gets into the whole suffragette thing. Women get the vote, but Lucy's not done. She starts organizing for labor rights and integration and ending white supremacy in the South. She organizes interfaith, integrated unions in the South, which you can imagine was a pretty big deal at that time. She does it through the YWCA. She writes a pamphlet telling consumers to boycott companies that don't treat their workers well. Eventually, she becomes the CIO's ambassador to the South and spends the next 16 years of her life going to all these small towns where bad things would happen to anyone who tried to unionize, and explaining workers’ rights and why integration is good and racism is bad to pretty much anyone with any kind of power. Neat!

Emma Goldman

Though not a union organizer by trade, anarcha-feminist Emma Goldman's advocacy for workers’ rights and human dignity and freedom empowered workers and organizers throughout the country, and motivated them to stand up for their own rights. She was considered the most dangerous woman in America for a reason.

She was a feminist, an anti-racist, an atheist, an advocate of free love, an opposer of the institution of marriage and — very unusually for the time (she pretty much started right after Haymarket, which was 1886, and continued until her death in 1940) — one of the first advocates of gay rights.

"It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of a different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding for homosexuals and is so crassly indifferent to the various gradations and variations of gender and their great significance in life."

I could probably go on about Emma Goldman forever, but I have to get to other people and also this is not my sophomore year in college.

Rosina Tucker

Rosina Tucker is best-known for helping to organize the first Black labor union, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, started by A. Philip Randolph in 1925. A Brotherhood? But she was a woman, you say! Well, the Pullman porters wanted to organize, but they were afraid of losing their jobs — with good reason, because their bosses kept trying to fire them for trying to unionize. So Rosina and other wives of the porters got together and started the Ladies Auxiliary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in order to raise funds to start the union.

In 1963, along with A. Philip Randolph of the BSCP, she helped organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and continued to be active in civil rights and labor rights until she passed away in 1987, at the age of 105.

The women on this list, along with the many others who also fought for labor rights in this country and others, didn't only fight a fight for workers. They fought a feminist fight, they fought for civil rights, they fought for human rights — they understood the interconnectedness of it all, they understood that without economic justice there is no social justice and without social justice there is no economic justice. They understood the way that the labor movement could be used as a catalyst for making social change possible at a time when they didn't have any political support or power — and that's a thing we could all do well to remember ourselves.

Happy Labor Day!

Wonkette is independent and fully funded by readers like you. Click below to tip us!

"The people have the power

The power to dream, to rule

to wrestle the world from fools

it's decreed the people rule

it's decreed the people rule

Listen

I believe everything we dream

can come to pass through our union

we can turn the world around

we can turn the earth's revolution

we have the power

People have the power"

-Patti Smith

https://youtu.be/pPR-HyGj2d0?si=OlmAohg9g7B9EBqk

The movie post is up, today it's a 𝐋𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐫 𝐃𝐚𝐲 𝐌𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐞 of 𝐂𝐥𝐞𝐫𝐤𝐬.