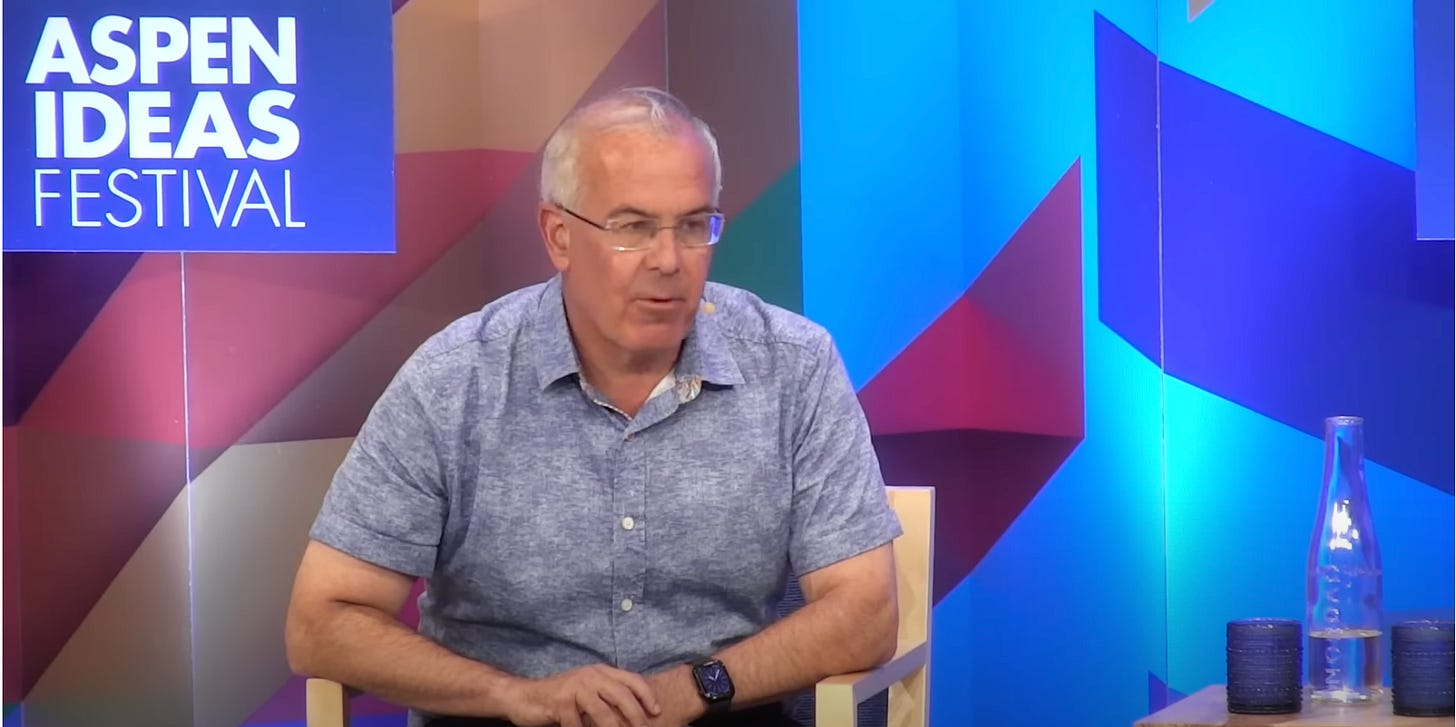

Is America Meaner Now Than When It Lynched People? David Brooks Unsure.

This man gets paid so much money.

David Brooks is absolutely clueless about the world around him. This has been obvious for years, yet major publications still offer him a platform for his rhetorical rake-walking exercises. In September’s The Atlantic, Brooks laments that American society has suddenly become “mean.” This is the same guy who wrote in 2015 that the poor have “no basic codes and rules woven into daily life, which people can absorb unconsciously and follow automatically.” You know, like not dumping your wife for your much-younger research assistant. That seems pretty mean!

The Atlantic article’s sub-hed declares, “In a culture devoid of moral education, generations are growing up in a morally inarticulate, self-referential world.” No, it doesn’t get better from there.

Before Brooks asks, “Why Americans so mean?” he first wonders “Why Americans so sad?” with some cherry-picked data that mostly ignores how minorities were very “sad” during segregation but no one cared to ask. Oh, and your 1950s traditional housewife was zonked out of her skull but hey, Dad came home to his dinner every night!

But on to the meanness:

I was recently talking with a restaurant owner who said that he has to eject a customer from his restaurant for rude or cruel behavior once a week—something that never used to happen. A head nurse at a hospital told me that many on her staff are leaving the profession because patients have become so abusive.

Yep, you read correctly: Brooks has built his article’s premise on the bedrock foundation of anecdotal evidence.

Bouncing assholes from your establishment is hardly new. It’s an entire profession. Also, that’s far better than the “bad old days” when restaurant owners rejected customers based on their skin color or sexual orientation.

Brooks acknowledges that “different social observers have offered different stories to explain the rise of hatred, anxiety, and despair.” For instance, social media’s driving everyone bonkers. We are more isolated in general, despite our more immediate social media connection. America’s growing diversity has triggered a white, cis male panic. Income inequality has most of us fighting over the remaining scraps. However, Brooks has his own theory that’s unburdened by peer-reviewed data or rudimentary logic.

The most important story about why Americans have become sad and alienated and rude, I believe, is also the simplest: We inhabit a society in which people are no longer trained in how to treat others with kindness and consideration. Our society has become one in which people feel licensed to give their selfishness free rein. The story I’m going to tell is about morals. In a healthy society, a web of institutions—families, schools, religious groups, community organizations, and workplaces—helps form people into kind and responsible citizens, the sort of people who show up for one another. We live in a society that’s terrible at moral formation.

This is a very conservative position, one easily disproven by observable reality and an honest look at our history. Slavery, systemic racism, misogyny, anti-gay discrimination aren’t just mean. They’re downright nasty and they have existed since this country’s founding. It was church-going people with supposed “traditional values” who recoiled at the thought of a child with AIDS attending the same school as their kids. This was in the mid-1980s, well before the Internet and social media had become convenient scapegoats for society’s ills.

It’s also important to remember that true meanness was taught. It was tradition and dehumanizing “etiquette.” It was the social norm. It’s how you separated the very white wheat from the marginalized chaff.

He goes on:

Beyond the classroom lay a host of other groups: the YMCA; the Sunday-school movement; the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts; the settlement-house movement, which brought rich and poor together to serve the marginalized; Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, which extended our moral concerns to include proper care for the natural world; professional organizations, which enforced ethical codes; unions and workplace associations, which, in addition to enhancing worker protections and paychecks, held up certain standards of working-class respectability. And of course, by the late 19th century, many Americans were members of churches or other religious communities. Mere religious faith doesn’t always make people morally good, but living in a community, orienting your heart toward some transcendent love, basing your value system on concern for the underserved—those things tend to.

The whiteness here is blinding.

The obvious question to the slogan “Make America Great Again” was “When was it so great?” The question Brooks’s privileged nostalgia raises is “When was America nicer than it is today?” Was America “nice” when local home owners associations conspired to keep ethnic minorities out of their neighborhoods? Was America “nice” when church groups and religious communities ostracized queer people or anyone the slightest bit different?

It’s easy to think America is meaner when Marjorie Taylor Greene is showing off Hunter Biden’s “gifts” during a House Oversight Committee hearing. Perhaps that’s true, but it’s also kinder in many ways. Black people can live and eat wherever we want now, unconstrained by red lines, and the LGBTQ community doesn’t have to hide itself to maintain a one-sided “peace.”

This might cause the mean-spirited to snarl and lash out viciously, but let them. It’s not the struggle that’s mean. It’s the status quo.

Follow Stephen Robinson on Bluesky and Threads.

Subscribe to his YouTube channel for more fun content.

Catch SER on his podcast, The Play Typer Guy.

America was nicer from about 4:00 to 8:30 PM on October 14, 1992, and it's been all downhill since then.

>> "It’s not the struggle that’s mean. It’s the status quo."<<

What a killer fucking conclusion, SER. I know you know you're a good writer, but there is good writing and there's those moments of genius. Maybe it's in part because I have high standards, but I read a lot of articles here by you and others and never feel the gut punch I received at the end of this one.