Mississippi Judge Begs Supreme Court To Fix Its Made-Up 'Qualified Immunity' Sh*t

It's like a poem.

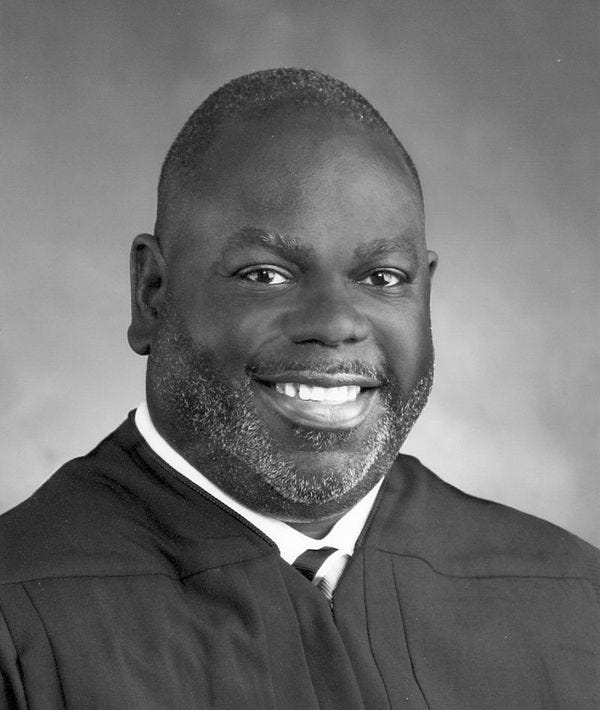

This week, United States District Court Judge Carlton Reeves wrote one of the most moving court opinions I have ever read.

Judge Reeves is only the second Black man to serve as a federal judge in Mississippi. There have been no Black women to hold that position. After law school, Reeves clerked for Rueben Anderson, the first Black justice on the Mississippi Supreme Court. In 1990. This, in a state where nearly 40 percent of residents are Black.

The good judge's opinion in Jamison v. McClendon actually grants qualified immunity to Nick McClendon, the white police officer in Pelahatchie, Mississippi, who pulled over Clarence Jamison (probably because he was a Black man driving "too nice" of a car). But Reeves makes it very clear that he is granting qualified immunity only because, as a district court judge, he is required to follow the law of the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit. And he implores the justices of Supreme Court to revisit this antiquated doctrine that frequently denies justice to people whose constitutional rights have been violated.

The beginning of the opinion could be a poem.

Clarence Jamison wasn't jaywalking.

He wasn't outside playing with a toy gun.

He didn't look like a "suspicious person."

He wasn't suspected of "selling loose, untaxed cigarettes."

He wasn't suspected of passing a counterfeit $20 bill.

He didn't look like anyone suspected of a crime.

He wasn't mentally ill and in need of help.

He wasn't assisting an autistic patient who had wandered away from a group home.

He wasn't walking home from an after-school job.

He wasn't walking back from a restaurant.

He wasn't hanging out on a college campus.

He wasn't standing outside of his apartment.

He wasn't inside his apartment eating ice cream.

He wasn't sleeping in his bed.

He wasn't sleeping in his car.

He didn't make an "improper lane change."

He didn't have a broken tail light.

He wasn't driving over the speed limit.

He wasn't driving under the speed limit.

No, Clarence Jamison was a Black man driving a Mercedes convertible.

After each line is a footnote saying their names.

Michael Brown. Tamir Rice. Elijah McClain. Eric Garner. George Floyd. Philando Castile. Tony McDade. Jason Harrison. Charles Kinsey. James Earl Green. Ben Brown. Phillip Gibbs. Amadou Diallo. Botham Jean. Breonna Taylor. Rayshard Brooks. Sandra Bland. Walter Scott. Hannah Fizer. Ace Perry.

Let's talk about qualified immunity

As we've explained at you in the past, "qualified immunity" is a doctrine entirely created by reactionary activist judges. The Supreme Court first mentioned qualified immunity in the 1960s . And in 1982 , more than a century after the 1871 Civil Rights Act (aka Section 1983 for its place in the US Code) became law, the Rehnquist Supreme Court stepped in to be like, "You know what?! We should make it harder for people to have any legal recourse when government actors violate their basic human rights!" This was perhaps a matter particularly close to Chief Justice William Rehnquist's heart. And that's how the doctrine of qualified immunity came to be.

In theory, qualified immunity can sound fairly innocuous. In practice, it's an absolute nightmare.

As Judge Reeves notes,

Tragically, thousands have died at the hands of law enforcement over the years, and the death toll continues to rise. Countless more have suffered from other forms of abuse and misconduct by police. Qualified immunity has served as a shield for these officers, protecting them from accountability.

Now, when a court hears a civil rights case, it asks two questions: Was a constitutional right violated? And if so, was that right "clearly established" at the time of the incident? If the answer to either of these questions is no, the judge has to dismiss the case. And since the inception of the qualified immunity doctrine — again, in 1982 — courts have bent over backwards to be like, "Nah, these rights weren't clearly established" and sweep civil rights violations under the rug.

Judge Reeves reminds us that

The Constitution says everyone is entitled to equal protection of the law – even at the hands of law enforcement. Over the decades, however, judges have invented a legal doctrine to protect law enforcement officers from having to face any consequences for wrongdoing. The doctrine is called "qualified immunity." In real life it operates like absolute immunity.

Not to mention the fact that

every hour we spend in a § 1983 case asking if the law was "clearly established" or "beyond debate" is one where we lose sight of why Congress enacted this law those many years ago: to hold state actors accountable for violating federally protected rights.

Sometimes, it seems like each case the Supreme Court hears, they create even more hurdles for people whose rights have been violated.

Each step the Court has taken toward absolute immunity heralded a retreat from its earlier pronouncements. Although the Court held in 2002 that qualified immunity could be denied "in novel factual circumstances," the Court's track record in the intervening two decades renders naïve any judges who believe that pronouncement.

Clarence Jamison

So what, exactly, happened when Clarence Jamison was stopped by police?

As he made his way home to South Carolina from a vacation in Arizona, Jamison was pulled over and subjected to one hundred and ten minutes of an armed police officer badgering him, pressuring him, lying to him, and then searching his car top-to-bottom for drugs.

Nothing was found. Jamison isn't a drug courier. He's a welder.

Unsatisfied, the officer then brought out a canine to sniff the car. The dog found nothing. So nearly two hours after it started, the officer left Jamison by the side of the road to put his car back together.

Thankfully, Jamison left the stop with his life. Too many others have not.

While granting qualified immunity to Officer McClendon, the judge makes it clear that he doesn't want to.

This Court is required to apply the law as stated by the Supreme Court. Under that law, the officer who transformed a short traffic stop into an almost two-hour, life-altering ordeal is entitled to qualified immunity. The officer's motion seeking as much is therefore granted.

But let us not be fooled by legal jargon. Immunity is not exoneration. And the harm in this case to one man sheds light on the harm done to the nation by this manufactured doctrine.

As the Fourth Circuit concluded, "This has to stop."

Reconstruction, Section 1983, and the KKK

Clarence Jamison's case was brought under the Civil Rights Act of 1871. Reeves reminds us of how it came to be.

Jamison brings his claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, a statute that has its origins in the Civil War and "Reconstruction," the brief era that followed the bloodshed. If the Civil War was the only war in our nation's history dedicated to the proposition that Black lives matter, Reconstruction was dedicated to the proposition that Black futures matter, too.

Reeves spends pages teaching us about the brutal backlash and terrorism from white supremacists, including the newly formed KKK, during Reconstruction. He reminds us that lynching and white supremacist terrorist attacks were ubiquitous and particularly terrible in his home state.

The terrorism in Mississippi was unparalleled. During the first three months of 1870, 63 Black Mississippians "were murdered ... and nobody served a day for these crimes." In 1872, the U.S. Attorney for Mississippi wrote that Klan violence was ubiquitous and that "only the presence of the army kept the Klan from overrunning north Mississippi completely."

He also reminds us that "[m]any of the perpetrators of racial terror were members of law enforcement."

It's important to know this history; without it, we can't fully understand the present. Or, as Reeves puts it,

For Black people, this isn't mere history. It's the present.

It's also important to grasp this history in order to understand the law this case is about, which when it was enacted by Congress, was called the "Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871." (Quotations omitted.)

The Act's mandate was expansive. Section 2 of the Act provided for civil and criminal sanctions against those who conspired to deprive people of the equal protection of the laws. Sections 3 and 4 authorized the use of federal force to redress a state's inability or unwillingness to deal with Klan or other violence. The Act was "strong medicine."

That is, until the white supremacists regained their power. Then,

For almost a century, Redemption prevailed. Lynchings, race riots and other forms of unequal treatment were permitted to abound in the South and elsewhere without power in the federal government to intercede. Jim Crow ruled, and Jim Crow meant that "[a]ny breach of the system could mean one's life." While Reconstruction "saw the basic rights of blacks to citizenship established in law," our country failed "to ensure their political and economic rights." Our courts' "involvement in that downfall and its consequences could not have been greater."

The reactionary "Redemption" Court of the late 1800s, the same court that decided Plessy v. Ferguson, gutted the Civil Rights Act. It wasn't until 1971 that the Court attempted to revive the Ku Klux Klan Act — and it did that only to gut it again just a decade later.

Or, as Judge Reeves titles a section of the opinion, "Qualified Immunity: The Empire Strikes Back."

And,

[j]ust as the 19th century Supreme Court neutered the Reconstruction-era civil rights laws, the 20th century Court limited the scope and effectiveness of Section 1983.

To demonstrate just how pro-police qualified immunity has gotten, the judge gives us a number of real examples.

A review of our qualified immunity precedent makes clear that the Court has dispensed with any pretense of balancing competing values. Our courts have shielded a police officer who shot a child while the officer was attempting to shoot the family dog; prison guards who forced a prisoner to sleep in cells "covered in feces" for days; police officers who stole over $225,000 worth of property; a deputy who body-slammed a woman after she simply "ignored [the deputy's] command and walked away"; an officer who seriously burned a woman after detonating a "flashbang" device in the bedroom where she was sleeping; an officer who deployed a dog against a suspect who "claim[ed] that he surrendered by raising his hands in the air"; and an officer who shot an unarmed woman eight times after she threw a knife and glass at a police dog that was attacking her brother.

So ... yeah.

And, of course, you can't look at Mr. Jamison's case without considering this history.

Jamison's traffic stop cannot be separated from this context. Black people in this country are acutely aware of the danger traffic stops pose to Black lives.

Civil suits can often be the only recourse a family has when a loved one is killed by police. Because, of course, "law enforcement officers are rarely charged for on-duty killings, let alone convicted[.]"

Abolish qualified immunity

Qualified immunity was created by the Supreme Court and it can be abolished by the Supreme Court. And Judge Reeves all but begs our current Court to do just that.

Our nation has always struggled to realize the Founders' vision of "a more perfect Union." From the beginning, "the Blessings of Liberty" were not equally bestowed upon all Americans. Yet, as people marching in the streets remind us today, some have always stood up to face our nation's failings and remind us that "we cannot be patient." Through their efforts we become ever more perfect.

The U.S. Congress of the Reconstruction era stood up to the white supremacists of its time when it passed Section 1982. The late Congressman John Lewis stared down the racists of his era when he marched over the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The Supreme Court answered the call of history as well, most famously when it issued its unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education and resigned the "separate but equal" doctrine to the dustbin of history.

The question of today is whether the Supreme Court will rise to the occasion and do the same with qualified immunity.

Let's give Judge Reeves the last word on this one:

Instead of slamming shut the courthouse doors, our courts should use their power to ensure Section 1983 serves all of its citizens as the Reconstruction Congress intended. Those who violate the constitutional rights of our citizens must be held accountable. When that day comes we will be one step closer to that more perfect Union.

Here's the full opinion.

Follow Jamie on Twitter !

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

needz stronger prescription!

Fuck you Bernstein.Just fuck you.