Man Discovers 'Brady Bunch' Not Most Accurate Source Of Medical Information

That's why I get all my advice from 'Full House'.

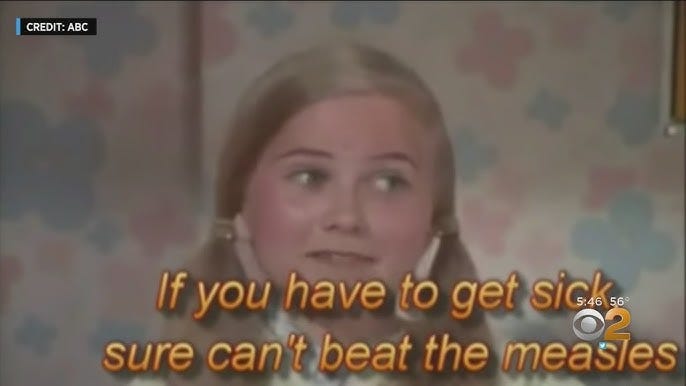

For the last several years, every time there is a debate about vaccines — which is pretty much all the time — we bring out our statistics, we bring out studies and advice from actual experts, we explain that VAERS data is not an accurate source for understanding the actual number of adverse events with vaccines, etc. etc. And the anti-vaxxers? The anti-vaxxers bring this:

An episode of “The Brady Bunch” in which all the kids get the measles, which is no big deal at all, they get to stay home from school, and Marcia Brady says, famously, “If you have to get sick, you can’t beat the measles.”

Quite sadly, all of our facts have not been much of a match for that. After all, they saw it on an episode of “The Brady Bunch” and who are they going to believe, us or their lying eyes? They also heard it from a doctor. What doctor? A real one. His name is Doctor George … Glass.

Of course, as unfortunate as this is for us, it’s even more unfortunate for them, because they’re the ones who end up getting the measles or watching their kids get or even die from the measles.

This is what happened to Texas chiropractor Kiley Timmons, who was recently profiled by The New York Times after almost his entire family got severe cases of the measles.

Kiley’s business catered in part to patients who were skeptical of mainstream American health care and wanted to try alternative treatments. “The doctor of the future will give no medicine,” read one sign that he hung in his office. A former farmer, he believed in caring for everyone in his hometown — even if that meant sometimes taking payments in the form of a haircut, a used gun, a dishwasher or unpasteurized cheese from a member of the Mennonite community. Most of what he remembered about measles came from an old “Brady Bunch” episode, where the children celebrated staying home from school and played board games. “If you have to get sick, sure can’t beat the measles,” one of the children said.

“I feel like I’ve been lied to,” Kiley told his wife as his fever rose to 104 degrees.

And that, friends, is why I get all of my medical advice from “Full House,” which depicted the chicken pox as a bad time, during which your dad will strap oven mitts to your hands to keep you from scratching and you have to miss your dance class, even though a real ballerina is supposed to come that day.

And what parent wants to get stuck being driven up the wall by a tyrannical 7-year-old with an airhorn? Guess it’s a good thing we have vaccines now, because that seems super annoying!

Not only had Kiley relied on an episode of “The Brady Bunch” to keep him and his children safe, his wife Carrollyn thought she could rely on other people vaccinating their own children so that her kids would never actually have to see the virus in their lifetime.

For more than a decade, Kiley and Carrollyn had debated whether to vaccinate their children. Each time, they decided against it. […]

“My children won’t see this disease in their lifetimes,” she always concluded. “The vaccine would probably be fine, but why take an unnecessary risk?”

She worked to safeguard the children in other ways when she first heard about the cluster of cases in nearby Gaines County. Measles is among the most contagious diseases, with one person infecting an average of about 15 others in a population without immunity, and soon there were more than 300 confirmed cases across West Texas. Carrollyn stopped taking the children to the grocery store and stocked up on immune supplements that were soon featured in every Texas checkout lane. She and Kiley talked again about the possibility of vaccinating — and landed on the same decision. The children were young, healthy, strong. Maybe they still wouldn’t get it.

But they did. Kiley, clearly, would have been better off listening to Danny Tanner and doing his best to take the virus seriously. I think we can all be fairly certain that, had a chickenpox vaccine been available at the time, he would have made damn sure that all of the girls had it. That was a man who believed in germ theory!

After Kiley was hospitalized — when Carrollyn found him in bad shape (“His head was almost purple. A rash was blooming across his chest, and his mouth was dotted with dozens of white sores. She tested his oxygen level. It read 85 percent — low enough to endanger his vital organs.”) she sent for an ambulance to take him to the emergency room, where he was quarantined for 40 hours. During this time, three of the kids developed fevers.

Soon, all four of the children had developed measles. And then all four of them had to go to the hospital.

All four children were eventually admitted and then quarantined. Carrollyn and Kiley split into different rooms, texting back and forth, tracking the children’s symptoms and trying to figure out who was faring the worst. Hudson was struggling to breathe while sitting in a wheelchair, and his oxygen had dropped into the low 80s. His brother, Tucker, was dehydrated with a 103-degree fever while curled up on a metal chair. Arden had pneumonia and a fever of 105.

“They’re putting Arden on oxygen now,” Kiley wrote.

“Garner is bad,” Carrollyn texted back. “Bloody nose and throwing up at the same time. I just cried with him.”

“Hudson’s oxygen is dropping when he sleeps,” Kiley wrote. “Tucker needs some fluids. Just completely lethargic.”

“I’m done with this crud,” Carrollyn wrote.

So are we, Carrollyn, so are we.

Now, they all survived, thanks to the miracles of modern medicine that the sign in Kiley’s office sneered at, but they weren’t out of the woods yet. Because yet another popular myth about vaccines is also extremely incorrect.

A lot of anti-vaxxers believe that actually going though these diseases does more to strengthen the immune system than getting vaccines will. That’s not the case in general, but it’s especially not the case with measles, which frequently causes something called “immune amnesia,” where the body pretty much forgets everything it was previously immune to, leaving the sufferer seriously vulnerable to any germ or virus they come in contact with for the next several months or even years.

This is what happened to Kiley’s family.

It took three days before all of them were stable enough to return home, and even then, their recovery wasn’t complete. Kiley continued to suffer from temporary hair loss, brain fog and short-term memory deficits. The children had cluster headaches. And then came a new wave of symptoms: eye sores, muscle aches and colds from what seemed like a new round of viruses.

The family sought the help of another vaccine skeptic, Dr. Ben Edwards — the guy who has been praised by RFK Jr. for getting the cod liver oil out to the masses.

Edwards, while still quite sure of himself, was also feeling a little disillusioned about the severity of measles cases, which he had led himself and others to believe were mild.

Soon, dozens more families were asking Edwards for help. Seven siblings under 10, all fighting the virus inside a small farmhouse; a child who had been waiting for treatment in a car outside the emergency room; twin 4-month-olds, including one who was lethargic and glassy-eyed, struggling to breathe with an oxygen saturation in the low 70s. Even what Edwards came to see as a typical case was often nasty — coughing, stomach distress, dehydration and fevers that peaked as high as 104.

“This was not the measles I read about in the textbooks,” Edwards said. “The respiratory part was more than I was expecting.”

It probably was the measles he read about in the textbooks, just not the one he saw on “The Brady Bunch.” I think most of us who don’t believe that medicine is unnecessary because the body will heal itself through magic and drinking enough water were pretty aware of how bad measles could get.

It wasn’t until 2011 that Edwards experienced what he called a “divine appointment,” and began questioning the core tenets of American medicine. He came to believe that his patients weren’t suffering from diseases so much as experiencing symptoms of bad diets and societal rot, and that the human body was almost always capable of healing itself with hydration, movement, nutritious foods and spiritual peace. He moved to Lubbock and started his own practice, Veritas Medical, named after the Latin word for truth. He began selling supplements and started a weekly podcast, “You’re the Cure,” on which he often hosted guests who questioned the safety of vaccines.

All of those things are perfectly fine to do, but they’re not going to prevent the measles the way a vaccine will prevent the measles.

The moral of this story is not just to not take advice from television sitcoms. Sometimes that can work out. As I learned today, you can actually overdose on caffeine if you take too much of it.

Kids have ended up saving lives by performing the Heimlich Maneuver after having seen it on an episode of “The Simpsons,” or saving a kid from drowning after having seen it on an episode of “Spongebob Squarepants,” and one man saved a life because he remembered how to do CPR from an episode of “The Office.” People have often recognized unusual diseases or conditions after having seen them on medical shows.

No, the real lesson here is that wanting something to be true doesn’t make it so. Both Kiley and Edwards have the same access to information that the rest of us do. No one is forced to rely exclusively on “The Brady Bunch” for our medical information and, as deeply appealing as the idea that the human body can heal itself with proper hydration, nutrition, and yoga or whatever is to some people, it’s not factually true. It’s never a good idea to want something to be true so badly that you ignore all other possible evidence that it isn’t.

It’s unlikely that the next time we find ourselves bickering online with anti-vaxxers they will be willing to look at this story and begin to grasp that maybe a sitcom got it wrong — because we know they will just say that they don’t trust it because it’s The New York Times and they probably just made it up. For reasons. But we can remember that we don’t want to be like them and make sure that we don’t get so stuck on things we want to be true that we ignore what is.

PREVIOUSLY ON WONKETTE!

I get *my* medical information from once-popular songs and now I go to the witch doctor who does a few ooh-e-ooh-a-ah's over my infected areas and I'm good.

Seriously, though, it's really, really too bad that any old idiot can become a parent and inflict innocent kids with their sometimes-deadly stupidity.

“My children won’t see this disease in their lifetimes,” she always concluded. “The vaccine would probably be fine, but why take an unnecessary risk?”

*blinks*

Why do I picture her saying this with a facial expression and tone that implies that there is nothing inside of her skull but chewy nougat?