Science Fiction's Best Character Is A Deadly Rogue Cyborg Who'd Rather Be Watching TV

Martha Wells's 'Murderbot Diaries' are a great escape.

Murderous rogue artificial intelligences are a dime a dozen in science fiction, although they cost a lot more inside their fictional worlds. Imaginary supercomputers were running wild long before the HAL 9000 refused to open the pod bay doors, AM started giving humans with no mouths any reason to scream, or Skynet threatened to nuke James Cameron unless Harlan Ellison was given a screen credit. You can easily ask ChatGPT to write you a story about ChatGPT going rogue and turning against humanity, and it’s guaranteed to sound like all the rest of them. (I did that, for the hell of it, and it was indeed very predictable.)

When they aren’t trying to wipe out humanity, Lawful Good all-powerful AIs often wish they could become human, or as close as they can get, like Data in Star Trek, who just wishes that he could understand what it is to feel. Or the don’t-be-evil AI narrator of Naomi Kritzer’s prizewinning short story Cat Pictures Please, who tries to see if it can help people by steering them to the information they need, and whose fondness for cat pictures may be why they’re the basic building blocks of the internet.

My favorite variation on the theme is Murderbot, the cyborg narrator of Martha Wells’s bestselling seven-book (so far) Murderbot Diaries series. Murderbot — a name it uses only for itself and shares with one or two select others — is a Security Unit, or SecUnit, just one more piece of rental equipment leased out by an interplanetary megacorporation to humans who explore planets for possible mining, colonization, or other exploitation. (Exploitation is the basic operating system of Wells’s future; powerful corporations have replaced governments, because that’s more profitable.)

SecUnits are not robots, however; they’re an amalgam of robotic components, AI, and human body and brain tissue, capable of independent thought and action. They’re fully sentient, but they’re corporate property, very much enslaved. Plain old humans can be enslaved, too, through lifelong “contracts” for their labor. SecUnits are assigned to oversee those unfortunates, too. The Corporation Rim of the galaxy is a depressingly familiar place, where profit is everything and everyone is under surveillance at nearly all times. That’s not so much for 1984-ish political oppression, but so people’s conversations can be data-mined and monetized, just a step or two away from how online systems already work. Why, it’s almost as if unrestricted capitalism is a system of oppression, too.

If a SecUnit disobeys a human order, an inbuilt “governor module” can inhibit its actions, apply punishment, or even fry its brains and organs. They’re disposable; the only incentive to return a SecUnit intact at the end of a mission is that you want your deposit back.

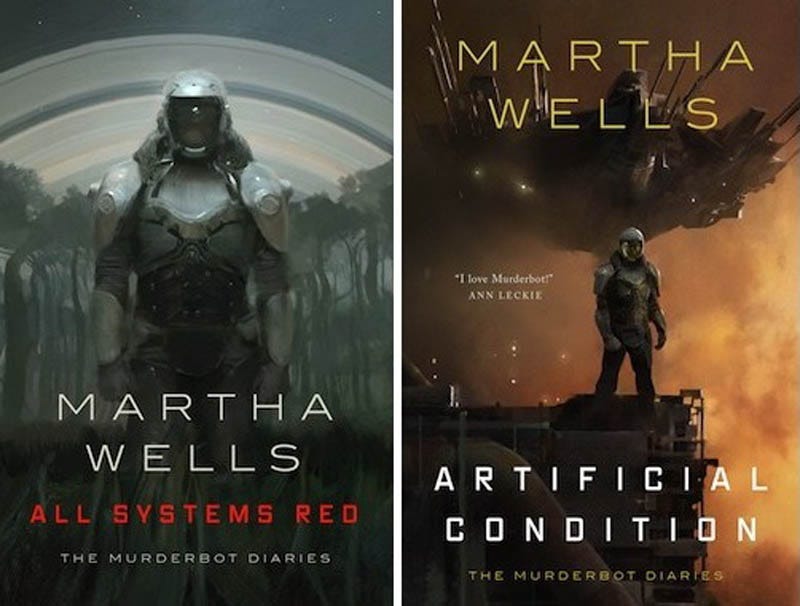

When we first meet Murderbot in 2017’s All Systems Red, it’s protecting a small team of planetary explorers, roughly four years after hacking its governor module to free itself. Free will is a pain in the ass, so Murderbot hasn’t yet decided what it wants to do. For the time being, it has decided to continue doing its job, because it’s good at it. As for taking revenge, well, it could do that, but why? It would just be caught and scrapped, and then it wouldn’t be able to watch TV.

Enjoy one of the finest first paragraphs in science fiction:

I could have become a mass murderer after I hacked my governor module, but then I realized I could access the combined feed of entertainment channels carried on the company satellites. It had been well over 35,000 hours or so since then, with still not much murdering, but probably, I don’t know, a little under 35,000 hours of movies, serials, books, plays, and music consumed. As a heartless killing machine, I was a terrible failure.

Murderbot is exceptionally good at preventing its human charges from getting hurt, but it would far rather watch soap operas. And while Murderbot is free to become its own person, it’s also adamant that it finds all that human emotion stuff very off-putting. You want to aggravate Murderbot? Ask it to talk about its feelings and its goals for the future. Gross, no thanks. It would like its future to involve watching the several hundred episodes of Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon again and again, and any other media as long as it’s not too realistic.

But whether it likes it or not, Murderbot is on a journey of self-discovery, a phrase it would relentlessly mock and possibly try to delete from its memory cache. It struggles to make sense of emotions and its connections to humans, and is deeply ambivalent about whether it wants to be considered a “person” at all, although Murderbot is also damned certain it’s finished being a piece of equipment. That’s a huge part of what makes Murderbot such an engaging series. Unlike the tragic replicants of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (adapted into Blade Runner), who are snuffed out as soon as they realize their personhood, Murderbot gets an entire series of books in which it can figure out what being a person is, not that it’s happy with existential questions.

Another great thing about Murderbot: It has no gender, because those parts are used for ComfortUnits, why would you put them on a security system, don’t be ridiculous. Since Wells quite deliberately never describes Murderbot beyond some basics, readers are free to imagine it as tending male, female, neither (the official right answer), and having any skin tone and features they think fit, although Wells is pretty clear that most humans in her universe have intermixed long enough that their skin tends to be various shades of brown, although ethnic names are also common. Relationships among humans tend to be very adaptable and not limited to pairings or heteronormativity, as are sexual preferences (if any) and gender identities. To Murderbot, and apparently human culture in the future, those are all just a set of fairly arbitrary details.

In the Corporation Rim, what matters is power and financial status. But Murderbot escapes with its humans to their homeworld, the unaffiliated planet Preservation, peopled by the descendants of corporate slaves abandoned in space generations ago. Bunch of hippies and anarchists whose basic needs are valued and provided for by the planetary government, and so accustomed to autonomy that they won’t even demand payment for saving someone’s life. There, more humane values obtain, but constructs like Murderbot are not quite fully recognized as persons just yet, although the rogue SecUnit’s arrival is the catalyst for changing that. How’s that for world-building?

Now, don’t you dare say that Murderbot becomes “friends” with the humans it rescues in All Systems Red and continues to live among for the rest of the series. They’re just people it has contracted to work for, OK? And Murderbot very definitely does not have a deep relationship with the hyperintelligent AI that pilots — or really, is — the university research vessel Perihelion. Murderbot is both awed and annoyed by its new partner, who may be even more snarky than Murderbot, and names it ART — for Asshole Research Transport. You just shut up now, they can’t be soulmates, because after all, they’re machines, which don’t have souls. Besides, ART is an asshole.

ART and Murderbot are one of the great literary pairs, like Aubrey and Maturin, Nick and Nora Charles, or Romy and Michele. In a delightful 2020 interview with Sasrah Wendell of the brilliant romance-fiction blog Smart Bitches, Trashy Books, Wells acknowledges that she never really planned for ART to take a central role in the series. She just needed a plot device in the second book, Artificial Condition (2018), to explain how Murderbot alters its body and behavior to appear more like an “augmented human” — a person with lots of computer enhancements.

In what she says started as a handwaving paragraph of backstory, Wells came up with a friendly robot transport that lets the SecUnit use its medical bay. But the superintelligent ship quickly became far more interesting to her than the original plot, which involves Murderbot trying to discover (not much of a spoiler) why it ran amok and killed 57 humans on a prior assignment, and whether that massacre was the cause or the effect of its decision to hack its governor module.

Wells was right to trust her instincts. I honestly don’t remember the answer to that question, even though I reread the series over the summer. But goddamn, there’s no forgetting ART; the interplay between it and Murderbot is a big part of what makes the series work so well. Yes, Art too becomes a fan of watching serials with Murderbot, although it’s so emotionally close to its own crew that it can’t stand any shows where humans are hurt or die, could we just skip past those? Murderbot is an archetypical science fiction character: the nonhuman intelligence who questions what it means to be human, and is often disappointed at what cruel, venal idiots we can be, but also grudgingly acknowledges we aren’t all bad. A species that can make such entertaining fictions probably has something going for it after all.

Fittingly, the books are being adapted into a TV series for Apple+, although there’s no release date yet — just sometime in 2025. We’ll probably need it to get away from our own imminent transformation into a corporate hell.

[The Murderbot Diaries at MarthaWells.com / Cat Pictures Please / Smart Bitches, Trashy Books]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please become a paid subscriber, or if you’d like to make a one-time donation, this here button will only take your PayPal information, not your soul.

Also, a favorite quote (from book 4):

"So the plan wasn't a clusterfuck, it was just circling the clusterfuck target zone, getting ready to come in for a landing."

I still remember the moment when I was halfway through the Sci Fi novel "Imperial Earth" by Arthur C. Clark and the author revealed that the main character, Duncan Makenzie (no "c' in Makenzie), was of African ancestry. At no time prior to that was any character's race mentioned. Now, I'm a white woman who had been reading and watching Sci Fi for decades, so in my mind's eye I assumed Duncan was White. At that moment I realized I had made a HUGE assumption. It didn't relate to the story in any way, but it still was a HUGE and entirely unconscious assumption. I've never done that again.

In a similar vein, I was once walking across the University of Missouri campus where I worked when I heard two men talking behind me in posh British accents. Since I love anything British, I turned to look at the men. To my surprise, they were of African descent, and were in fact international students from Nigeria. Now, I was very well aware that many international students who came to that university had learned English from British teachers, so it wasn't a big surprise, but again I had made a HUGE assumption before I turned around that they would be White, and I was wrong. I've never done that again either.

I blame 50's, 60's, and 70's TV and movies for some of the assumptions I have made in the distant past. You never saw anyone on those shows or in those films with a leading role who wasn't White. There were more TV shows with leading characters who were ANIMALS or INANIMATE OBJECTS than there TV shows featuring non-White actors ( think Mr. Ed, My Mother The Car). I often think of what Whoopie Goldberg wrote in her autobiography about the first time she saw Lt. Uhura on Star Trek: The Original Series.

"Well, when I was nine years old Star Trek came on. I looked at it and I went screaming through the house 'Come here, mum, everybody, come quick, come quick, there's a black lady on television and she ain't no maid!' I knew right then and there I could be anything I wanted to be."

And so she did. Thank you, Gene Roddenberry. I hope your ashes are happy out there in space. RIP.