Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks For Your Separate But Equal Homeschooled Darlings

Greetings, Time Tourists! We're almost finished with our visit to the 1950s as seen through the lens of rightwing Christian textbooks. This week, we'll look at the beginnings of the modern Civil Rights movement, and next week, we'll wrap up the decade with the books' coverage of the economic boom of the '50s. The important thing to remember about both of those developments is that they came about because Big Government got out of the way and let individual initiative thrive and prosper.

Both of the textbooks we've been reading take at least a partially mainstream view of Civil Rights history -- neither book will be mistaken for Eyes on the Prize, but considering their earlier soft-pedaling of slavery, their discussion of the Civil Rights movement seems almost radically fact-based by comparison.

The always hilarious 8th-grade textbook America: Land I Love (A Beka, 2006) suggests that the movement was a natural outgrowth of America's basic goodness and prosperity. In a section headed "Freedom and Opportunity for All Americans," we learn that Civil Rights movement just sort of happened:

The years after World War II brought greater opportunities for all ethnic groups. Minority peoples had served their country well during the war by working and fighting for freedom. Many Americans saw that the time had come to end racial prejudice. The first group to achieve more opportunities were black Americans, who wanted to guarantee a better life for themselves and their children under the legal protection of the Constitution.

And who do they present as the first hero of that achievement? Jackie Robinson, of course, probably because he was not "political." And then there's a couple of paragraphs on Marian Anderson, because why not throw her 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial into a chapter on the 1950s? In one of those amazing lies by omission that makes us admire this book so much, Land I Love can't even be honest about the central facts of that event:

officials in Washington, D.C., denied her the privilege of singing at Constitution Hall because she was black. Instead, Marian Anderson stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday morning of 1939 to sing for 75,000 Americans of all races and walks of life.

Darn those mean old racist "officials in Washington DC!" Kids reading Land I Love would understandably come away thinking that the federal government blocked her appearance at the presumably government-owned landmark Constitution Hall, when in fact that concert hall was privately operated by a private group, the Daughters of the American Revolution, those decent church-going women with their mean pinched bitter evil faces, who nixed the concert not because Anderson was black, but because she insisted that the audience not be segregated. And while in the textbook's telling, Anderson seems to have just shown up of her own volition on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, a real history book would note that the concert was arranged by the socialists in the Roosevelt administration, in response to a campaign by a coalition of churches, activists, and labor unions -- along with liberal members of the DAR, most prominently Eleanor Roosevelt, who resigned from the organization in protest. (Now, the DC city government did refuse permission for Anderson to perform at a local high school after the DAR turned her down, so "officials in Washington DC" has just enough shredded, processed fact in it that Politifact might well rate the account "mostly true.")

Land I Love finally gets to what most people think of as the Civil Rights movement, with five whole paragraphs on some major events in the '50s (and more, later, in the chapter on the 1960s). We get a quick mention of the 1954 Brown v Board of Education decision, though there's no mention of the crucial concept that "separate" is inherently "unequal" -- a point that U.S. History at least brings up in passing. Land I Love also acknowledges that "Some communities did not obey the Supreme Court order to desegregate their schools," and gives us the barest facts on exactly one example:

Governor Orval E. Faubus of Arkansas ordered the Arkansas National Guard to bar black students from Little Rock’s Central High School. President Eisenhower promptly sent 1,000 federal paratroopers to Little Rock to guard nine black students as they entered the local high school.

Strangely, this section doesn't contain a single defense of "states' rights," despite the book's praise for the concept elsewhere -- probably just a little oversight on their part.

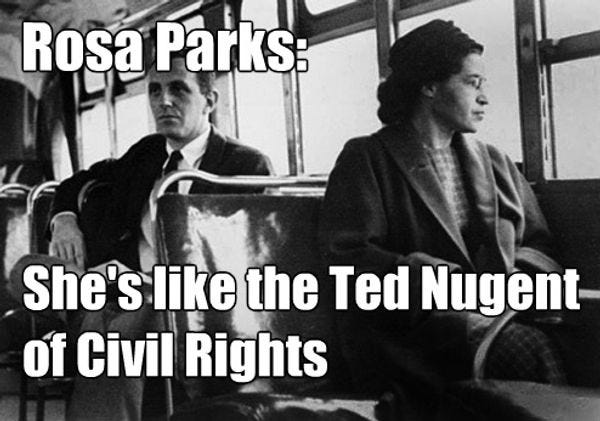

And then of course there's Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott; in keeping with Bad History Standards, both Land I Love and U.S. History depict Parks as merely a "tired black seamstress" who spontaneously decided not to give up her seat to a white man, rather than as a longtime member of the NAACP who very deliberately set out to defy segregation. While plenty of secular textbooks present the same simplified myth (which began circulating during the boycott itself), it's worth noting that better textbooks get it right. In any case, Land I Love at least gets the basic facts straight, noting that Martin Luther King helped organize the boycott, and that while it caused Montgomery's bus system to lose revenue, the boycott only ended when the Supreme Court "ordered Montgomery to desegregate its bus system" -- another partial fact, of course; U.S. History more accurately states that the Court's decision broadly "forbade discrimination in public transportation" as unconstitutional. And while the early days of the Civil Rights movement had many heroes and involved mass actions, Land I Love (like too many secular texts for young readers, too) simplifies the story by making MLK the Big Hero, because that makes tests a lot easier to take.

As you'd expect in a high school text, U.S. History gives the topic more detail, and even takes the time to distinguish between the nitpicky and common usages of the term "Civil Rights":

Technically, a civil right is a specific privilege or entitlement that is granted by law and that the government is responsible for actively protecting from both government and individual encroachment. In modern American history, however, the phrase "civil rights movement" refers primarily to attempts by blacks to secure the exercise and protection of their civil rights.

U.S. History goes over pretty much the same ground; Brown v Board of Education, with more detail, the Little Rock Nine, with only slightly more detail (and again, not a single mention of how Eisenhower ran roughshod over states' rights by sending in federal troops), and Rosa Parks and Montgomery, in more detail, with a considerably more detailed look at King and his Christian roots, plus his admiration for Thoreau and Gandhi. Surprisingly, the book doesn't pass judgment on whether King was an orthodox enough Christian -- you'd think at the very least they'd tut-tut a bit over his modernist ecumenical leanings.

Unlike their coverage of slavery, the problem with these books isn't so much that they get Civil Rights history wrong -- with the exception of Land I Love's distortions about Marian Anderson, it's all factual enough. But there's no mention of just how all that segregation came into place, or of the vicious lengths the white establishment went to in order to resist change. Emmett Till, the Scottsboro Boys, lynching, the White Citizens' Councils, all of the machinery of segregation just goes unmentioned. We'll come back to this in coming weeks, when we cover the 1960s, but here's a little spoiler for you: King's "I Have a Dream" speech makes it into both books, obviously, but neither text makes any mention of the bombing of Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church a few weeks later, or the 1964 murders of voting rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. There's a Civil Rights movement in these books, and they treat it as a good thing, because yay America and freedom and equality, but there's barely a hint of the actual cost of the struggle. Your Christian textbooks, published in South Carolina (Bob Jones) and Florida (A Beka), wouldn't want to make the South look bad, after all.

Next Week: Economic prosperity in the 1950s and why the government had nothing to do with it.

Follow Doktor Zoom on Twitter. He enjoys "mostly true" history.

Random encounter with an anti-comma.

<i>Ask not what your government can do for you. Ask how you can drown your government in the bathtub.</i>