The Cass Review: Hey, What Does UK NHS Trans Report Mean?

Not afraid to write 1900 words at you!

So. The Cass Review. Hoo, boy. Or girl. Or you non-binary you. You are all beautiful to Yr Wonkette. Possibly-maybe not so much to Britain’s National Health Service, however.

Oh, you have not heard of the Cass Review? Well, there is a great deal of talk about this thing in all the trans corners of the internet, and maybe you should know about it. A few years back, when the Tories were still very pleased with the stunning success of their Brexit referendum and were not yet measuring prime ministers’ tenures in millicabbages, the UK government solicited an independent review of gender-related medical service provision for minors. The person then tasked to oversee this review is Dr. Hilary Cass, and that report has now been released. With appendices it is 388 pages which Yr Wonkette will now explain in the remaining 1900 words of this article.

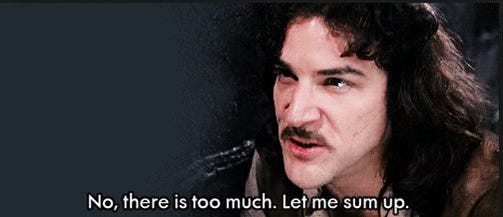

Okay, fair. Let’s sum up then. The Cass Review is a wonky, sciencey, jargony document that gives every appearance of being a Tory project intended to justify cracking down on medical care for trans people in the name of non-trans people who feel icky when forced to think repeatedly for weeks on end about surgeons coming for their genitals — but it nonetheless contains a few good things. Ultimately, however, it seems insufficiently independent and includes minimal and often perfunctory pushback against that Tory agenda from an academic who wanted to at least create the appearance of fairness. It includes 32 recommendations and 139, 153, or possibly 168 “key points,” depending on how seriously you take the report’s numbering. There is SO MUCH to cover, and trans journalists and activists have been covering endless details, but we shall limit ourselves here to those recommendations and key points.

The good:

As expected, the final report remains consistent with the summary report issued in 2022 in recommending increased geographic access to treatment. In response, the NHS is moving toward providing services at several regional centers, or “centres,” and the report advocates that services disperse even farther, possibly through part-time clinics where a single group of clinicians spends a certain amount of time each week or month at a different location, thus minimizing travel distances for patients and families. (A single regional centre with its associated clinics is referred to as a “multi-site service network”.)

It further recommends that these MSSNs be implemented “as soon as possible.” Which, it’s only words, but the words are good.

The Review also recommends money be allocated for resources and training to ensure that all clinicians can provide care that meets expected standards without delay or confusion due to lack of available staff or lack of competent and knowledgeable staff.

The report maintains a positive ultimate goal: “The central aim is to help young people to thrive and achieve their life goals.”

It includes a recommendation of support for parents, other carers, and siblings, which is YAY, TEAM!

The meh:

Cass and her team seem to have found some significant problems with care provision. These appear to be mainly limited to poor documentation of services rather than poor service, but without the documentation, you never know. Yr Wonkette is never happy to see bad care, but we’re always happy when the bad care that does happen gets identified so that it can be remediated and not repeated.

In the past, the entire UK had only one centre providing “GIDS” (gender identity services), nicknamed Tavistock. Tavistock was quickly closed after the summary report, but those MSSNs are not entirely up and running yet. It is not clear if they have taken on any new patients in the time — over a year — since Tavistock closed. More service centres are good, but do we really have them yet? Or do we effectively have no service at all?

One recommendation is that these youth-oriented MSSNs serve everyone up to age 25 rather than, as is currently the case, up to age 17. While there are some non-shitty rationales for this, such as making care access easier for young adults in a time of many transitions by maintaining a consistent care provider or potentially making long term outcome research easier, there is quite a lot of reasonable fear that a centre historically focused on serving minors will be ill equipped to address the needs and concerns of adults with appropriate respect for their agency. Also, too, if they’re not taking anyone, then that’s worse than being on a waiting list for adult services, which at least occasionally take on new patients.

Despite minimizing the legitimacy and value of the WPATH standards of care, the Cass Review recommendations mirror these in a number of ways, such as the insistence on a truly individualized care plan with responsive management allowing for patients to stop as well as start interventions based on what is healthy in the moment without creating an expectation of or commitment to a specific long-term trajectory of care. This is a good thing, and it’s wonderful that it is being recommended to the NHS, but it is disturbing that the WPATH standards are portrayed as contrary to this model.

Let’s also not allow the previous point to be misunderstood: While taking credit for recommending some things that the WPATH recommendations include, the spirit of the Cass Report is very different from the WPATH recommendations even when the letter is similar. WPATH, for instance, recommends highly individualized care with no commitments to a long term clinical trajectory and no presupposition that what appears most likely to be best right now will remain the best thing over time. It also recommends support for parents, carers, and siblings. The Cass Review recommends these as well, but while WPATH emphasizes listening to clients, the Review emphasizes following national standards and delaying and discouraging care. Despite superficial similarities on a number of points, these are not small differences.

Cass also recommends that services be offered to detransitioners. While on the one hand, of course, on the other hand … in order to make this recommendation, they’re forced to use different, lesser standards of evidence than they use for service recommendations for trans clients. Yr Wonkette knows from gender hell, and we do not wish it on anyone without support, but recommending service interventions for folks who detransition when there literally isn’t any non-anecdotal research on what these people are experiencing, much less whether any interventions might exist to help them, much less exactly what those are? That leap to provide service contrasts sharply with the hesitance throughout the report to provide services to trans kids and young adults where evidence does exist but is not, in the opinion of Cass, sufficiently strong. The stark difference calls into question the entire report’s repeated assertion that it seeks to recommend only treatment that can be justified by high-quality published evidence. It is beyond bizarre that they recommend treatment in a medical setting with no idea what clinicians might do, or why, or whether it has any likelihood of being effective.

The bad:

The report stresses the lack of “high quality” evidence — defining that as double-blind randomized, controlled studies (RCTs). But it’s impossible to conduct a blind study of social transition, much less a double-blind one. Likewise with certain hormonal therapies. Defining “highest quality” in such a way as to be impossible for research on this topic to meet is at best a failure to understand what doctors should expect from clinical research on trans-presenting children and adolescents, and at worst a politically motivated choice to camouflage unreasonable premises as reluctant conclusions.

The review is rather obsessed with the Cooties Hypothesis. Over and over and over it refers to increasing case loads and a shifting gender profile. While it also notes that it considers certain proposed explanations inadequate, there is no skepticism to be found in the key findings or recommendations of the tCH in its various forms.

The stress that children and adolescents are to be treated as complex individuals deserving of highly specific treatment addressing each patient’s unique situation rings hollow against consistent recommendations that treatment be withheld, delayed, or discouraged.

The insistence that all care has to meet a single standard for high quality, justified by high quality research, and consistent across regional MSSNs is only a good idea if the national standards are themselves both good and flexible enough to accommodate the needs of very different patients and if high quality research is both defined and identified appropriately. Otherwise the NHS could just as easily be institutionalizing bad practices and guaranteeing bad care.

Remember all that good stuff? It requires money to make happen. What are the odds that the Tories invest in care for trans children and what are the odds that Tavistock stays closed while the new MSSNs never get funding?

The ugly:

Parents and adolescents accessing hormones or puberty blockers outside of NHS authority was portrayed as bad and dangerous behaviour by those parents and adolescents, but not as a crisis of legitimacy for the NHS. While unsupervised consumption of prescription drugs can be dangerous, the Cass Review seems never to struggle with the fact that this is the NHS’s fault and seems entirely unaware that their approach blames the victims. Children need care. Parents are desperate to provide it. The NHS has proven unresponsive in the past and now it has become even harder to access care. Of course some of those desperate people are going to make bad decisions. Of course. Cass may as well have been lecturing the hungry on the ethics of stealing bread.

The report includes an informal recommendation against social transition (meaning that the text wasn’t contained within its 32 official recommendations, but embedded in a “key point”). Yet it seems never to grapple with the ethics of this. The Review insists that social transition should be considered an NHS health intervention, but what does that mean? Should the NHS have the power to forbid name changes? Nicknames? Haircuts? It also treats social transitions as creating the demand for medical transitions as the persons who socially transition are much more likely to go on to seek medical transition. Not only does the Review see medical transition as a bad outcome to be prevented, but obvious confound is obvious.

In other contexts, too, the report treats medical transition as a failure to be avoided rather than one equally valid approach among many for addressing an individual’s situation. Worse, the Review worked with groups who seek to end all medical transition around the globe, and there are a number of reasons to believe that the report shares at least partially the vision of ending trans existence. That sounds extreme but is the express goal of groups that the Review takes seriously and whose input Cass solicited.

Before we wrap up, there’s also some truly weird Alice-in-Wonderland shit in the Report. Take this:

Innovation is important if medicine is to move forward, but there must be a proportionate level of monitoring, oversight and regulation that does not stifle progress, but prevents creep of unproven approaches into clinical practice. Innovation must draw from and contribute to the evidence base.

Is it just Yr Wonkette or does that sound exactly like Dolores Umbridge justifying the Ministry of Magic interfering at Hogwarts?

“Every headmaster and headmistress of Hogwarts has brought something new to the weighty task of governing this historic school, and that is as it should be, for without progress there will be stagnation and decay. There again, progress for progress's sake must be discouraged, for our tried and tested traditions often require no tinkering. A balance, then, between old and new, between permanence and change, between tradition and innovation...”

If nothing else makes clear why trans people in the UK are afraid that this Review is an extended exercise in providing political cover for the Tories to hack away at trans care, that would.

Finally, and it’s hard to quantify or clarify this, but trust us: The Cass Review does not take its own premises seriously. One example is the use of the phrase “sex of rearing” instead of “gender of rearing” as if Cass genuinely doesn’t understand the difference between sex and gender — though to the knowing it seems much more likely to be a conscious embrace of the anti-trans “gender critical” position that gender does not exist, only sex does. But also, consider this from Assigned Media:

[A] pattern appears of some papers showing a psychological benefit of the intervention, a smaller number showing no change positive or negative, and no papers showing any psychological harm. For example, in the systematic review of the evidence on puberty blockers, several included studies suggested psychological benefits to treatment in a range of areas, while a smaller number of studies found no significant impact. This was summarized in both the papers and the Report as “weak evidence” but could also be accurately described as “weak evidence (in favor of treatment).”

Recommendations against treatment are not neutral. In a clinical environment such as recommended in outline by the Review in which services are accessible, it is the norm to have one consistent primary specialist plus the support of several others specializing in other necessary fields, and where the approach is consistently tailored to the child or adolescent in question and constantly monitored for any needed or helpful changes, a recommendation against treatment is not needed. Knowledgeable specialists will have the chance to work with the patient in a close way over a long period, allowing the patient time and helping the patient to achieve insight into, as one example, whether anxieties or other negative symptoms are most closely related to gender or to sex or to both.

The Cass Review, however, does not trust the process it recommends, repeatedly advocating an individualized approach that shifts at need, while simultaneously stereotyping or clustering patients in ways that create treatment expectations for groups, not individuals.

And while treatment provision is perhaps weakly supported by available evidence (though there are plenty of cogent arguments that this underestimates the strength of the research), generalized delay or discouragement is strongly contraindicated. The available research shows no statistically significant harms from previous practices in the UK, and where we have anecdotes of persons who have been harmed (in the UK or elsewhere) they are invariably accompanied by stories of poor clinical practice not in keeping with either the WPATH recommendations or the Cass Report’s own. In order to make a general recommendation for delay or discouragement by the research standards adopted by Cass, there would have to be statistically significant harms identified first, and then follow up research would have to show that a generalized delay/discourage approach reduces those harms to a statistically significant degree. Cass simply does not have the evidence to make such recommendations, not by her report’s standards, and not by more reasonable, contextualized ones.

In other words, no, of course medical treatment isn’t appropriate in every case, but Cass insists that she cannot recommend treatment where in the past it has been considered appropriate by competent clinicians. She asserts this is because the evidence is weak while also insisting that she can make recommendations against treatment when the evidence is literally non-existent. The hypocritical standards render the Review worthless as an unbiased piece of research.

Which is a hell of a shame, because children, adolescents, and adults who are trans or just experiencing gendered or sexed anxiety deserve better than this.

Whoops! I forgot to link back to the earlier Wonkette article in which I elaborated on the Cooties Hypothesis! I have now fixed that if you refresh, or if you prefer to find it right here, here ya go!

https://www.wonkette.com/p/how-many-forests-did-the-new-york

***It also treats social transitions as creating the demand for medical transitions as the persons who socially transition are much more likely to go on to seek medical transition.***

That sounds like the "gateway drug" accusation about weed. If you start by interviewing people who underwent medical transition, you will find that 100% of them started with social transition. Now cue the knee-jerk reaction.