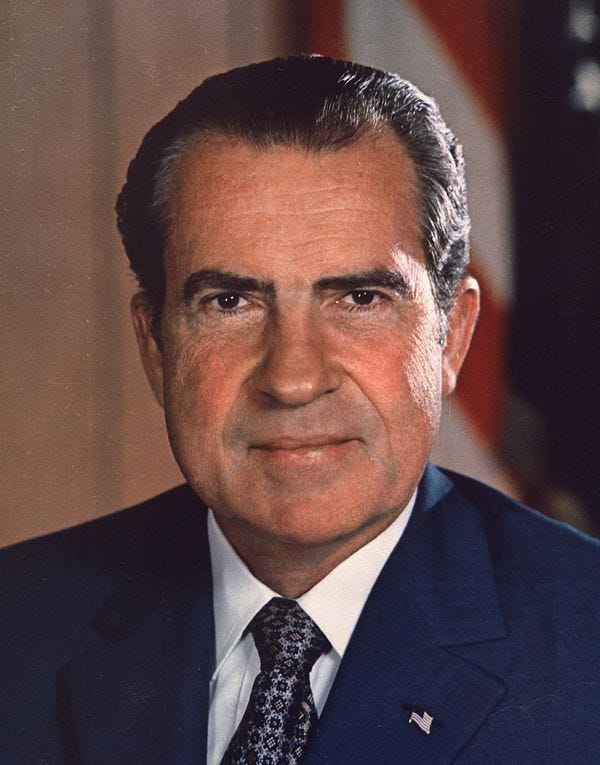

The Day Nixon Went To China We Mean The Coal Mine Safety Act

Man, what couldn't that criminal do!

On December 30, 1969, Richard Nixon, although he hated doing so, signed the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act into law. The first comprehensive legislation in American history to protect the lives of coal miners, it came only after tens of thousands of deaths in mine accidents and even more deaths from black lung and other breathing problems of the mines.

Through most of the period since the Civil War, the coal companies had treated Appalachia as their own little fiefdom, almost completely controlling life in these isolated places and engaging in maximum violence to eliminate union organizers, especially in particularly isolated West Virginia and eastern Kentucky. The United Mine Workers of America finally broke through and unionized the mines in the 1930s under the leadership of John L. Lewis. But the conditions of work were still extremely dangerous. While workers themselves had long worried about safety on the job, the attention of union officials to these issues was not always the greatest. Coal mining always had a fatalism about it, with the assumption of the inevitability of some deaths. Between 1906 and 1970, there were 90,000 officially reported fatal accidents in the bituminous mines alone, as well as 1.5 million job related injuries between 1930 and 1969.

The companies consistently fought against any meaningful actions on workplace safety. What’s more outrageous was the indifference of the United Mine Workers leadership to the death of miners. The law only gained momentum after the Farmington Mine Disaster of 1968. Gas and dust exploded at a mine near Farmington, West Virginia, that had a long history of similar problems. This horrific event killed 78 miners. UMWA president Tony Boyle basically didn’t care. He was more concerned with good relations with the companies than protecting his workers. At the press conference after the disaster, Boyle told reporters, "As long as we mine coal, there is always this inherent danger. This happens to be one of the better companies, as far as cooperation with our union and safety is concerned.’’ Miners were furious. They began to organize against Boyle and his thugs who ran the union like dictators. Key to their complaints was the union stealing health and safety funds to line their own pockets. The specter of immediate death from accidents and slow death from black lung spurred grassroots organizing within the union to fight against the leadership.

With virtually no help from Boyle or top UMWA leaders, the Black Lung Associations managed to publicize the plight of workers and get Congress to push for a coal mine safety law. The BLAs, led by young miners back from Vietnam or Midwestern cities where they had exposure to the tactics of the civil rights movement, led highly public actions such as shutting down the statehouse in Charleston, all in direct defiance of Boyle. The strikers demanded that West Virginia allow for a multiplicity of ways to test for black lung, agreements to fund health and pension programs in exchange for mechanization that threw people out of work to be honored, and expanded workers comp. The protest succeeded and West Virginia passed a new law with these demands in 1969.

The success in Charleston led to a movement toward federal legislation. The Johnson administration had introduced a coal mine bill in 1968, but it died along with much of the late Great Society over Vietnam and Johnson’s downfall. The Farmington disaster and worker protests led the government to act more seriously in 1969. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate and 389-4 in the House. Nixon did not want to sign the law. As with much of the environmental and workplace legislation he signed, he did so quite reluctantly and only after fighting to weaken the bill. He threatened a veto over the black lung compensation program, leading to 1,200 workers going on strike. But seeing the inevitability of the legislation, he signed it.

The law mandated at least two annual inspections at above ground mines and four in underground mines. Miners had the right to request federal inspections. Violators were fined and could be criminally charged if egregiously negligent. Coal miners began to receive periodic x-ray exams for black lung ( a process that however has become deeply corrupted and captured by industry ) and the right to demand less dangerous work when doctors detected black lung. The law also created a federally administered black lung benefits program.

The Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act was a precursor of the Occupational Safety and Health Act , passed the next year and providing a more comprehensive set of protection to all Americans at work. But like OSHA, the implementation of FCMHSA was limited as business began organizing against workplace safety enforcement. The mine owners challenged the constitutionality of the law and lost. But the tide would soon turn. In addition, these agencies take a while to become effective, something the miners quickly realized when the Hurricane Creek Mine Disaster in 1970 killed another 38 workers in a mine with a long history of indifference to safety. In 1978, a further expansion of the law that would have granted workers themselves the right to test the air for dust was rejected as a violation of property rights in a newly conservative and anti-union America.

The same grassroots outrage that forced Boyle and the UMWA to support the legislation did not abate, leading to Jock Yablonski's challonge to Boyle’s leadership. Yablonski ran for the presidency of the UMWA in 1969, saying, “Today I am announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United Mine Workers of America. I do so out of a deep awareness of the insufferable gap between the union leadership and the working miners that has bred neglect of miners’ needs and aspirations and generated a climate of fear and inhibition.” He ran on a platform of health and safety, including a greater emphasis on fighting against black lung.

Yablonski was “defeated,” in the sense that Boyle committed massive fraud to keep himself in office. A mere week after the legislation passed, Boyle had Yablonski murdered in his home by thugs . Miners for Democracy came out of these acts, demanding the overthrow of Boyle, which succeeded with federal supervisions for elections and Boyle’s arrest for Yablonski's murder.

As of 2007, over 600,000 miners and widows had received several billion dollars in benefits from the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act.

FURTHER READING:

Daniel Fox and Judith Stone, “Black Lung: Miners Militancy and Medical Uncertainty, 1968-1972,” in Judith Walzer Leavitt and Ronald L. Numbers, Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health

Daniel Curran, Dead Laws for Dead Men: The Politics of Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Legislation

Alan Derickson, Black Lung: Anatomy of a Public Health Disaster

Chad Montrie, To Save the Land and People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia

William Graebner, Coal-Mining Safety in the Progressive Period: The Political Economy of Reform

James Whiteside, Regulating Danger: The Struggle for Mine Safety in the Rocky Mountain Coal Industry

Mark Bradley, Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America

Please keep Wonkette paying its writers properly, if you are able!

Correct. In this part of Cali, we have compost bins. That's where paper things that have food on them go.

Stitch them in. You'll thank me later.