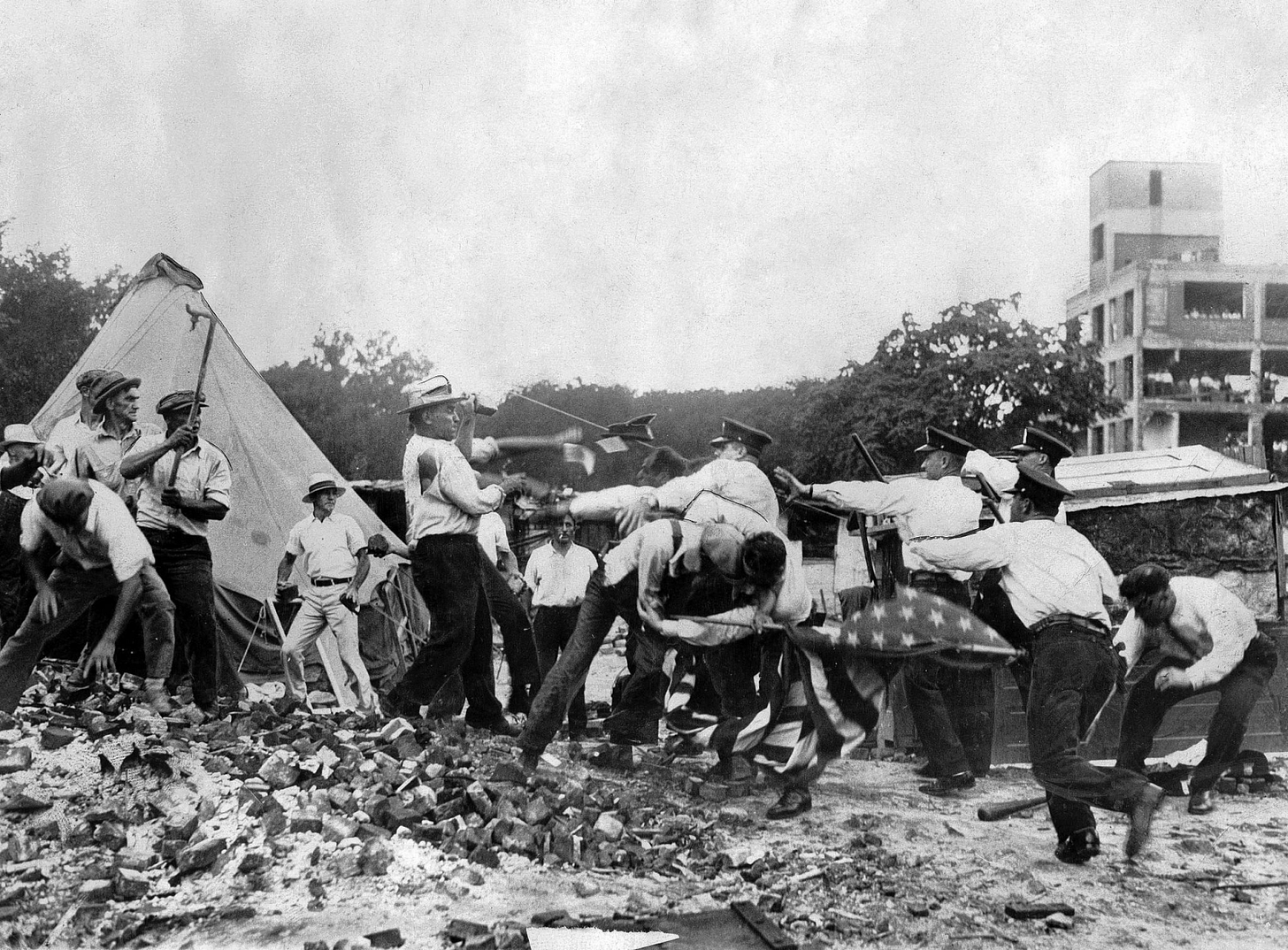

When Patton And MacArthur Burned The Bonus Army Veterans' DC Camp Like It Was Atlanta To The Sea

Yesterday in labor history!

On July 28, 1932, the US Army 12th Infantry regiment commanded by Douglas MacArthur and the 3rd Calvary Regiment, supported by six battle tanks commanded by Major George Patton, violently evicted the Bonus Army from their Washington DC encampment. This horrible treatment of impoverished veterans shocked the American public and demonstrated the utter indifference of Herbert Hoover to the desperate poverty the nation faced, helping to seal his overwhelming defeat that fall that ushered in the widespread change of the New Deal that would follow.

The Great Depression absolutely decimated the American working class. Unemployment shot up to 25 percent by the winter of 1933, while underemployment affected perhaps an additional 25 percent of workers. Herbert Hoover was simply unable to deal with these problems. Hoover was a man with a long humanitarian record, but he was very much a Progressive in a period where the voluntarist response to social problems that movement valued no longer worked. (Look how labels change!) Charges that Hoover didn’t care about the poor are overstated. But he simply could not accept any large-scale state involvement in solving the problem. By the summer of 1932 he had slightly moved off his position, but widescale social programs were anathema. Even more horrifying to him was worker activism and protest.

In 1924, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act that granted World War I veterans a one-time pension check — in 1945. President Calvin Coolidge vetoed this bill because of course Coolidge would veto a bill that gave anyone a dime, but Congress overrode the veto. But by 1932, those soldiers needed that money now. They faced unthinkable poverty. They could not feed their families. What difference did it make if it was 1932 or 1945, veterans thought. So they began to demand the immediate payment of their bonus. The bonus was not a huge amount of money. It paid veterans $1 a day for service while in the US and $1.25 in Europe, up to a maximum of $500 in the US and $625 in Europe. That $625 is about $8,000 today. This was not going to make people rich. But it was something at a time when something was exactly what was needed.

As the Depression deepened, Congress did allow veterans to borrow against the value of the certificates. Originally, they could borrow up to 22 percent of the total, but in 1931 Congress expanded this to 31 percent. Congressional support for paying the entire bonus grew. In January 1930, 170,000 desperate veterans applied for the loans —in nine days. Veterans struggled with what must have been PTSD, as Veterans Administration studies in 1930 and 1931 showed that veterans had unemployment nearly 50 percent higher than non-veterans of the same age. Beginning in 1930, Congress began exploring new bills to help veterans, but none became law. Then, on June 15, 1932, the House passed the Bonus Bill that would grant the bonuses immediately.

As Congress debated the Bonus Bill, veterans descended on Washington, demanding the immediate payment of the bonus. Organizing this protest was an organization you might not expect today — the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The VFW had few members in the early 1920s. But after 1929, its membership exploded because it supported the immediate payment of the bonus, while the American Legion, a proto-fascist anti-worker organization in addition to supposedly advocating for veterans, opposed it. They created a Hooverville in what is today Anacostia Park. Despite being in Washington during the summer, they maintained sanitation. They did not welcome non-veterans or other radicals who might want to turn the event to their purposes. To stay in the camp, people had to prove their veteran status and eligibility. They could however bring their families. Approximately 20,000 veterans traveled to Washington during the summer of 1932.

VFW leaders presented Congress with a petition from 281,000 veterans demanding their money. Veterans camping was an annual event for the VFW. Thus, the act of setting up in one place was not radical, nor unusual, although the official 1932 encampment was in Sacramento. But that year, camping in DC had a specifically politically agenda. The movement for a specific Bonus Army came out of Oregon. Veterans hopped trains and headed east. Thousands joined them. The VFW did not precisely endorse the Bonus Army and wasn’t quite affiliated with it, but many VFW locals sent supplies and provided other forms of support.

Hoover refused to even meet with the veterans, although he spoke at American Legion conventions on at least two occasions. While the House passed the bill, the Senate overwhelmingly rejected it, 82-18, with Hoover strongly opposing it.

For the most part, the Bonus marchers accepted their defeat. Congress even passed a bill to pay for their transportation to go home. Most left, but not all.

Herbert Hoover was very nervous about the remaining bonus marchers. The Washington police force had no patience for the Bonus marchers and neither did the military. The remaining marchers began squatting in government buildings. Hoover ordered them cleared. The police were happy to do so. This led to skirmishes.

That led Hoover to order MacArthur to clear out the camp. But Hoover was pretty clear — this was not to be violent. MacArthur disobeyed his orders and burned the whole camp. After he demolished the camp, he told the press that the Bonus Army was full of communists. That Douglas MacArthur, what an American hero. MacArthur’s actions absolutely devastated Hoover’s re-election chances, if he still had them in July 1932. Franklin Delano Roosevelt would obliterate Hoover in November, creating a rare complete realignment of American politics. The VFW strongly supported Roosevelt, wanting revenge on Hoover for what happened to the Bonus Army.

The Bonus Army was not a movement with a radical or unionist agenda. But it was a clear expression of working class activism transforming America by the early 1930s, new energy that generated greater explosions of worker activism in the next few years that forced the government to pass laws like the National Labor Relations Act, Social Security Act, and Fair Labor Standards Act.

Interestingly, Franklin Roosevelt did not support paying the bonus either. There was another march in 1933. FDR provided them a camp site in Virginia and three meals a day but did not publicly support their goals. Finally, in 1936, Congress passed a bonus bill. FDR vetoed it. But Congress overrode it and much of the bonus was paid early.

FURTHER READING

Steven Ortiz, “Rethinking the Bonus March: Federal Bonus Policy, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the Origins of a Protest Movement,” in the July 2006 issue of Journal of Policy History

Paul Dickson and Thomas B. Allen, The Bonus Army: An American Epic

Stephen R. Ortiz, Beyond the Bonus March and GI Bill: How Veteran Politics Shaped the New Deal Era

Harvey Ferguson, Defender of the Underdog: Pelham Glassford and the Bonus Army

1932 is when my great uncle Alfred finally died from the effects of mustard gas at age 34, in case anyone every wondered why my grandfather was a died-in-the-wool Democrat.

I know, I know...I live in the desert and its hot here yadda yadda.

But this is NOT good.

It has been 110°F and over for 30 days now. It hasn't cooled off below 90°F for over 3 weeks. Not normal.

The noble Saguaros, designed by Nature to live here, are dropping dead because they can't cool off at night.

https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/saguaro-cacti-collapsing-arizona-extreme-heat-scientist-says-2023-07-25/