Wonkette Presents THE SPLIT: Chapter Three

In which our heroine receives a promotion and prepares to celebrate.

As she cleaned up, Lorinda was thinking about how much she liked talking to people, entertaining them. And how much they seemed to like it: The crowd around the bar was always bigger when she was behind it. It was 10:10 PM and Linette, the night girl, had checked in. Lorinda stopped by the office in the rear, beyond the kitchen, to say good-night to the branch manager.

“See you tomorrow, Mrs. Barker.”“Can I have a word with you, Lorinda dear?” Mrs. Barker was in her forties or fifties — it was hard to tell — and, as usual, was dressed like an off-duty lady rodeo champion. She waved Lorinda in toward the visitor’s chair.

Uh, oh, thought Lorinda as she sat. “Busy tonight, huh?”

“Lorinda,” said Mrs. Barker, “I think you know we appreciate your work.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Barker. You know I like it here.” What’s the catch, Lorinda wondered.

“Bless your heart. And that’s why I’m not going to call you Lorinda anymore, but … Miss Head of Bartending Operations!”

It took a second for it to sink in. Lorinda’s eyes went wide. “Oh my gosh!” she said. “I mean, that’s fantastic! Thank you! I can’t believe it.”

“You’re on your way to big things, Missy. I wouldn’t be surprised if you’re sitting in this chair in a year or two. You’ve got a good head on your shoulders.”

“But,” said Lorinda, “What about you? We need you. Where would you go?”

“Oh, don’t worry about little old me,” said Mrs. Barker. “I’ve got my eye on a corner office at headquarters.”

“In Dallas?”

“That’s right.”

“And your husband?”

“Old Charlie loves Dallas. Or,” she whispered even though no one else was in range, “he will by the time I get done with him.” She really made herself laugh with that one.

“Wow, Dallas,” said Lorinda. “I’d love to travel. I’ve only been out of Perfecton once. My parents took us to New Orleans. And of course I was born up north.”

“Where did your people come from?”

“Upper State New York,” said Lorinda. “They left during the Great Moratorium.”

“That was sure a crazy time,” said Mrs. Barker. “Well, they were smart to get out of that diabolical hellhole while they could. And I can see their smartness rubbed off on you. You’re a lucky girl to be here. If you were still there you’d probably be a prostitute or a drug addict. Or both. Or you’d be mentally ill from all …” Here she whispered. “… the abortions. Or a communist. Praise God for Texas! CCSA! The best!”

”I know!” Lorinda smiled. “Perfecton is so nice!

“Nice is what Perfecton is all about, my dear. It’s why our founders created it here. You know the motto: ‘A serene, wholesome place to live the modern conservative lifestyle —”

“— away from the temptations of Satan.’” Lorinda sighed. “It’s great. Not too much traffic, no potholes, usually. Good weather except for tornado season ...”

“We’re very blessed to live here. And I think you’re going to be a star as Head of Bartending Operations. You’ll start at the beginning of the month. You’ll get an orientation between now and then. Oh, and I didn’t even mention.” Mrs. Barker paused for dramatic effect. “You’ll be getting a two-hundred-dollar a week raise!”

“Wow,” said Lorinda, with as much fake enthusiasm as she could muster. As a regular, non-supervisory employee she was making PumpJack’s standard starting wage of two-hundred-fifty-six-thousand dollars a year, so the extra two-hundred wasn’t going to make that big a difference. But it was definitely a nice gesture, and a vote of confidence in her work.

“So,” said Mrs. Barker, wrapping up their meeting, “what are you going to do to celebrate your new position?”

Lorinda thought for a second. “I don’t know. Maybe I’ll go to this party a friend invited me to.”

“Oooh,” said Mrs. Barker conspiratorially. “Fun! Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do.”

They both had a good laugh over that one.

Lorinda studied herself in her bathroom mirror, touching up her makeup, giving her hair a little toss, checking out her tight-as-legally-permitted jeans, her sweater, her boots. She was glad to be out of her PumpJack’s uniform and into clothes that made her feel — she blushed slightly when she found the word she was looking for — sexy.

“Are you sure this is a good idea, honey?” said her mother, poking her head into the bathroom, trying to be as un-pushy as possible while still showing concern. “Seems awfully late to be going out.” In her early-forties, Mrs. Rita Moon was on the young side for the mother of PumpJack’s most popular bartender. On the other hand, with her short graying hair, saggy eyes, and baggy pink terrycloth bathrobe, she could pass for a good ten years older.

“Yes, mother. It’s a great idea. I’m celebrating my promotion with some of my friends. If I can’t celebrate that, what can I celebrate? I’m twenty-two years old. I’m not a baby.”

“That’s what we’re worried about,” said her father. Mr. Robert “Bob” Moon was also in his early forties. With his brush-cut dark hair, his well-worn khaki cargo pants, and his faded olive-green tee-shirt, he had a vaguely military look about him.

“Nothing to worry about, Dad,” said Lorinda, putting away her supplies and giving herself one last look in the mirror. “I’ll report any and all bad behavior to the Perfecton Police Department — or to the Security Bureau if it’s really bad. Like I always do.”

“When did you ever do that?” asked Mrs. Moon.

“Never,” said Lorinda. “That’s because I’ve never once seen any bad behavior. But I know who to call if I see any!”

“Don’t be a wiseass,” said her father. “And don’t forget — there are cameras everywhere.”

“Thanks, Dad.”

“And I just saw that there’s a heavy smog rolling in, so drive carefully. And if you can’t see, pull over and wait it out.”

“Okay, Dad.”

“Don’t stay out too late, dear,” squeaked Mrs. Moon.

“I don’t need to be at work until six tomorrow night. Saturday. Gotta go — I’m picking up Emmie. Love you guys.”

“Maybe I’ll be able to afford a new car once I get my raise,” said Lorinda.

“Two-hundred dollars a week? No way,” said Emmie, riding shotgun. She had traded her hospital scrubs for loose-fitting jeans and a blousy pink top.

“Yeah, I know. But you gotta dream.”

“You gotta dream,” echoed Emmie.

Rounding a curve, they came face-to-face with a pulsating billboard in bright LED lights, alternating between the headline “Oliver M. Waldrip — The Only Fundamentalist Candidate for CEO,” Waldrip’s grinning, unctuous puss, and his motto: “Education Is The Enemy.” Inevitably — it happened whether or not the car radio was on — they heard the sign’s audio, broadcast via the CCSA’s Short-Range Billboard Channel (SRBC): “Jesus has assured me He favors my candidacy. I know you voters will do the right, Christian thing.”

Suddenly, before the audio was even finished, the billboard disappeared behind an ashen charcoal cloud. “Oh dammit,” said Lorinda, hitting the brakes and slowing down to a crawl. “My dad warned me about this. Is your window closed all the way?”

Emmie checked. “Yeah. You don’t want to breathe it. That shit’ll kill you. You know how many people we get at the hospital every time there’s a smog event? A lot!” she said, not waiting for Lorinda’s guess. “And some of them always die. And the worst part is, the government blames us! The hospital staff! For not doing our part to Maintain the Population. You try to maintain the population when the air is like this!”

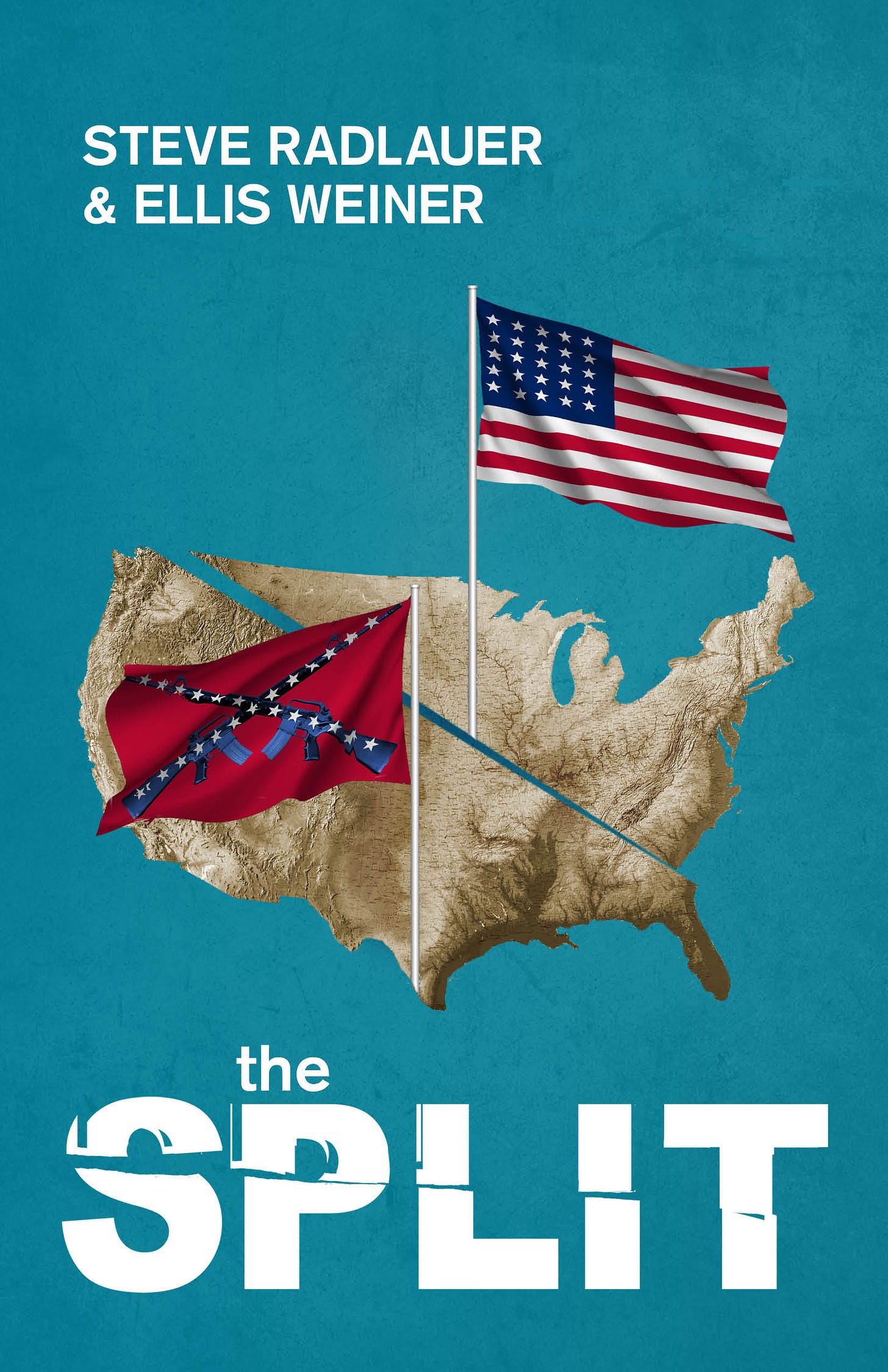

It was a familiar campaign, promoted by the government from the federal level on down to the states: “M.P.! Maintain the Population!” The truth — which the government never acknowledged, and about which every national and state official lied when asked — was that, during the two-year Moratorium after The Split, when anyone from either the CCSA or the USA could move from one to the other with a minimum of bureaucratic red tape, many people had fled the so-called red mostly-southern-and-midwestern nation for the so-called blue mainly-northeast-and-to-the-west-of-the-Great-Lakes country. (“We reject the term ‘fled,’” announced CCSA Secretary of Citizenship Laura Larsen. “We prefer ‘emigrated from.’”) What started out as a welcome, even triumphant “cleansing” (as it was unofficially referred to, even if the mass migration was entirely voluntary) of liberals, progressives, gays, trans, feminists, Jews, racial minorities, Muslims, Catholics, and other undesirables, ended up as a crisis of manpower. Yes, real conservatives, patriotic believers in freedom, and good Christians from up north re-settled in the south. But the bulk of the traffic flow was in the other direction, by an order of magnitude or two.

The result, in the newly birthed nation, was simply not enough bodies: a shortfall of workers for the fields and factories of the country’s crucial agricultural and dirty-energy sectors, a dearth of laborers to man (or woman) the nation’s factories (whether locally or foreign-owned), and a distinct lack of sufficient consumers to drive its hyper-capitalist economy. Sure, a national ban on abortion, with no exceptions, helped. But once the employment and economic numbers were in, the CCSA government found itself in the unfamiliar position of having to assist its citizens in the business of staying alive.

The question was: How?

Improving the material conditions of life — fixing dangerously unmaintained roads, mitigating industrial pollution of air and water, regulating the manufacture of food and drugs — required outlays of money, which in turn required the raising of what few nominal taxes there were, and creating new ones. This was considered politically unfeasible and morally reprehensible. And, of course, interfering with the private sector to improve people’s income, by establishing a minimum wage, enforcing safety standards, or permitting unions and collective bargaining, was deemed traitorous, “communistic,” and un-Christian.

Instead, the government turned to persuasion. It mounted a continuing and ever-evolving series of ad campaigns designed to encourage the citizens of CCSA to do everything they could both to remain alive, to help others remain alive, and — how to put this delicately? — to get married, have sex, and produce babies.

(There had been another campaign — hotly debated, uncertainly executed, and quickly abandoned. It involved advertising the charms and benefits of life in the CCSA in other countries, in the hopes of encouraging emigration. Sadly, what the nay-sayers predicted came to pass: No matter how carefully targeted the ads were, no matter how narrowly restricted to Western Europe, Scandinavia, and Russia, the citizens of those countries most susceptible to CCSA’s promises of total freedom, untrammeled individualism, and Southern hospitality, turned out to be the same non-white, non-Christian minorities whose lives in their home countries left much to be desired. “We don’t want Germany’s Somalis,” one politician railed. “We want Germany’s Germans.” After two months of watching Africans and Muslims de-plane at Dallas-Fort Worth, the Confederated government scuttled the campaign, fired all those responsible, and sent the dusky immigrants back to where they came from.)

Still, there was always the domestic drive for boosting the numbers. Was it working? It was hard to say. Just last year the government tried to assess the robustness of the population by conducting a nationwide census. But the fiercely independent citizens of the country — founded on the principles of Christian faith, conservative self-reliance, and proud disdain for “nanny state” meddling — refused to answer census workers’ questions.

Emmie was reflecting on her own sarcastic response to a mail-in census questionnaire (“How many people reside in your home?” “Does the dog count?”) when she found herself lurching forward as Lorinda smashed the brake pedal to the floor.

“What?!” Emmie was glad she’d remembered to use her seat belt, even though it wasn’t required by law.

“Something in the road. Lucky I saw it. Hold your breath for a second. I have to see what it is.” As Lorinda engaged the parking brake, both she and Emmie inhaled deeply. Lorinda got out of the car with a pause and a lurch, as though diving into a lake. She closed the door and carefully moved forward. Emmie watched until her friend walked around the large object in the road and disappeared from headlight range about a dozen feet beyond the front of the car. In a few seconds Lorinda came back.

“It’s a roof,” she said, closing the door behind her.

“A roof?”

“You know, those big things with shingles? On top of houses?”

“Tornado?”

“Must be. I didn’t see a tornado warning, but ...”

“Hey, they can’t warn us every time there’s a little tornado. They probably didn’t even know about it. I can’t tell you how many tornado victims we get in the hospital when we didn’t even know there’d been a tornado.”

“All right,” said Lorinda, “I can drive around the side, I think.” She released the parking brake and slowly eased the car past the roof, occasionally running over who-knows-what — some shingles? A chunk of roof beam? Then, as suddenly as it had appeared, the smog lifted as she steered the car back to the middle of the road.

“I haven’t been out this way before,” said Lorinda.

“Really nice houses,” said Emmie. ”You think that guy Brad owns one?”

“It’s his friend’s place, he said. Probably his friend’s parents’ place. I mean, come on.”

Without missing a beat, Emmie looked at the restaurant receipt in her hand. “Righteous Pathway. Number three-fifty-five. Too bad the GPS satellite is broken.”

“Here we go,” said Lorinda, spotting the street sign and turning right. “Righteous Pathway. Dumb name for a street.”

“Shhh. Someone might hear you.”

Make us look good, if you like it. Hit up the authors with a one-time or recurring donation!

Subscribe to the serial novel The Split here to get it in your inbox every Sunday, or see it at Wonkette every Monday a.m.!

PREVIOUSLY in THE SPLIT!

This is an enthralling tale thus far and my only complaint is that I have to wait an entire WEEK before reading the next excerpt. But that in itself provides my mind with the opportunity to ponder the potential directions present prose possesses and will take the tale as it proceeds forward.

And then there is the unnerving chill of familiarity with the confederate context of the scenario itself; none of this is beyond belief at this point in time.

How shocking that a conservative run state would fail so quickly!! Who would have seen this coming besides anyone who knows the history of Grafton, NH.

[insert archer gif: do you want bears? because this is how you get bears!]

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/21534416/free-state-project-new-hampshire-libertarians-matthew-hongoltz-hetling