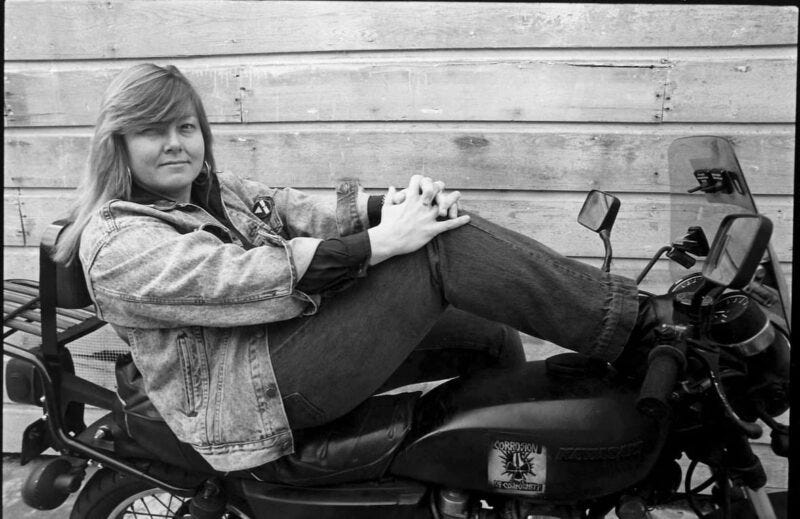

Dorothy Allison, Working Class Feminist, Author And Absolute Badass, Dies At 75

Oh, this is a hard week.

Two or three things I know for sure, and one of them is that if we are not beautiful to each other, we cannot know beauty in any form. — Dorothy Allison

I first read Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina when I was around 11 years old, and I don’t know that I’ve been as emotionally wrecked by any novel before or since — maybe not, because nothing sticks out just now for me.

Allison passed away this week, in the early hours of Wednesday, November 6, at the age of 75, “following a short illness with cancer.”

Born in South Carolina in 1949, she was a queer feminist, an activist, an author, a class warrior and genuinely kind and incredibly warm person. Her work dealt with themes of class, rape and sexual abuse (she was a survivor herself — like Bone, the protagonist of Bastard, she was sexually abused by her stepfather), sexuality, and infused these serious themes, somehow, with a humor that was so thoughtful it never seemed misplaced.

In addition to Bastard Out of Carolina, her published works include Trash: Short Stories, Skin: Talking About Sex, Class & Literature, Two or Three Things I Know For Sure and Cavedweller. She also wrote a lot of erotica, or what she liked to call “smut.”

Via LitHub:

In the 70s, Allison fomented with a rising feminist movement. Of her activist years in Florida and D.C., Allison wrote, “Part of my role, as I saw it, was to be a kind of evangelical lesbian feminist, and to help develop a political analysis of this woman-hating society.”

In the 80s, her socially minded work met literary aspirations. Allison edited the feminist newspaper Amazing Grace, and contributed essays, poems, and editorial insight to pubs like Quest, Out/Look, The Village Voice, and Conditions.

In her essay, “Notes To A Young Feminist,” published in In These Times in 2004, Allison lamented the overly academic “high-falutin’” language being used by many feminists and wrote about what feminism meant to her as someone who came to feminism from a working class background, as an “escaped Baptist” who saw it almost as a “religious conversion.”

I do not necessarily believe that someone can make it all make sense. I am, in fact, in love with the feminist ideal of “get used to being uncomfortable, you’ll learn something.” That is what I need, want, ache for, and I believe absolutely in the future of feminism.

I do not construct feminism as an ethical or moralistic system. When I talk about justice, I am talking about institutions that have ground me and my kind, right down to rock so far back that they owe me. They owe me as a working-class girl. They owe me as a queer girl. They owe me as a raped child. They owe me as a writer who had to raise money and who couldn’t write for years because she had to raise money. Yet, I also know that that voice saying “They owe me” is the most dangerous bone in my body. It is a part of me that I have to resist. It is a bone I cannot stand on, feel or shape. Instead, I owe you, my feminist sisters

In her essay A Question of Class, she wrote:

My aunt Dot used to joke, "There are two or three things I know for sure, but never the same things and I'm never as sure as I'd like." What I know for sure is that class, gender, sexual preference, and prejudice—racial, ethnic, and religious—form an intricate lattice that restricts and shapes our lives, and that resistance to hatred is not a simple act. Claiming your identity in the cauldron of hatred and resistance to hatred is infinitely complicated, and worse, almost unexplainable.

And

The horror of class stratification, racism, and prejudice is that some people begin to believe that the security of their families and communities depends on the oppression of others, that for some to have good lives there must be others whose lives are truncated and brutal. It is a belief that dominates this culture.

It is what makes the poor whites of the South so determinedly racist and the middle class so contemptuous of the poor. It is a myth that allows some to imagine that they build their lives on the ruin of others, a secret core of shame for the middle class, a goad and a spur to the marginal working class, and cause enough for the homeless and poor to feel no constraints on hatred or violence.

The power of the myth is made even more apparent when we examine how, within the lesbian and feminist communities where we have addressed considerable attention to the politics of marginalization, there is still so much exclusion and fear, so many of us who do not feel safe.

I grew up poor, hated, the victim of physical, emotional, and sexual violence, and I know that suffering does not ennoble. It destroys. To resist destruction, self-hatred, or lifelong hopelessness, we have to throw off the conditioning of being despised, the fear of becoming the they that is talked about so dismissively, to refuse lying myths and easy moralities, to see ourselves as human, flawed, and extraordinary. All of us—extraordinary.

All of this feels important right now, perhaps more than ever.

Allison was a veteran of the Feminist Sex Wars of the 1980s, having bravely fought on the side of sex-positive feminism and anti-censorship, in opposition to anti-porn crusaders Andrea Dworkin and Catharine Mackinnon. In 1981, she and Jo Arnone founded the Lesbian Sex Mafia, now the oldest running BDSM support and education group for cis and trans women (Yep! There were trans-inclusive feminists in 1981! Allison was one of them!)

If you haven’t read any of her works, I cannot recommend them enough, Bastard Out of Carolina, in particular — though you may want to wait a beat if you can’t handle having your entire heart ripped out at the moment. The movie based on the book, directed by Anjelica Huston and starring Jennifer Jason Leigh, Christina Ricci, Jena Malone and Laura Dern is also exceptionally good and available to watch for free on YouTube, though I’d recommend reading the book first.

I can’t say I knew Dorothy Allison, but I did meet her and speak with her several times while she was the writer-in-residence at the college I went to. I need you to know that she was absolutely lovely. I don’t know another word for it. She was just lovely — soft and hard at the same time, calm but intense, with a lilting, almost musical voice and she made me laugh and relax when I was an overwhelmed and slightly teary fangirl talking to her one-on-one for the first time. It was wonderful. She was wonderful. She will be missed.

Like Robyn I met Allison a few times, shared panel speaking-gigs with her, and even had the honour of introducing her at an event she headlined. I can't say that I know her or, fuck, knew her, but I told Trix an hour or two ago that I learned more about writing from reading Dorothy Allison than from any 6 teachers I've ever had.

If you've ever liked anything I've ever written, then you'll like more than half of everything Allison has ever written. She's that fucking good. Nobel in literature good. She's amazing.

"I grew up poor, hated, the victim of physical, emotional, and sexual violence, and I know that suffering does not ennoble. It destroys."

I've long believed this, which coincides with studies that say that the earlier a child has to "grow up" (read: confront the ugly realities of adult life), the worse off they are for it. And that Ernest Hemingway was mostly wrong in that some of us grow harder in the broken places, because he was mostly wrong about everything. We just pretend to be harder, to convince others and ourselves that suffering ever has intrinsic meaning.

RIP.