Our Prisons Are Scarring People For Life And Democratic Lawmakers Want To Know How To Help

Reps. Ayanna Pressley and Grace Napolitano want the National Institute of Mental Health to research post-traumatic prison disorder.

Every year, 640,000 people are released from US prisons. As disappointing as this probably is for "tough on crime" folks who would prefer that everyone convicted of a crime just stay in prison forever (whether or not they are actually guilty), this is a fact.

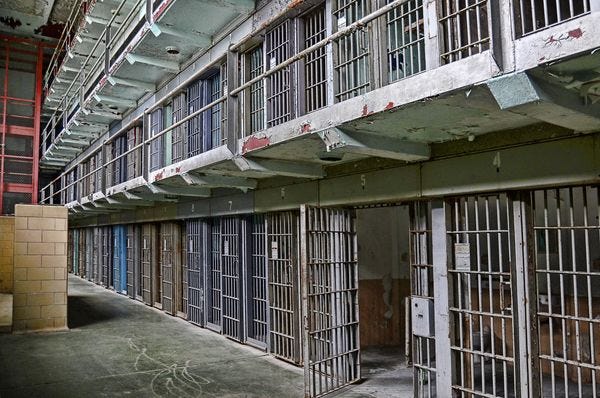

It is also a fact that being incarcerated is an incredibly traumatic thing for people to experience. I hate the term "common sense," but the logical conclusion that most people would draw after thinking about it for more than 30 seconds is that of course it's traumatizing to be locked up in a jail or a prison for any amount of time. How could it not be?

Given this, Democratic Reps. Ayanna Pressley (MA-07) and Grace Napolitano (CA-31) have written a letter to the National Institute of Mental Health, asking them to do more research on post-traumatic prison disorder, also called post-incarceration syndrome — so that when people leave jails or prisons, we know how to help them better adjust to the world outside.

Our national strategy to support people who are formerly incarcerated and end the cycle of mass incarceration must address post-traumatic prison disorder. Every year, more than 640,000 people are released from state and federal prisons. The status of their mental health is a major determinant of what happens next in their journey. Strengthening familial relationships, maintaining steady employment, and developing productive habits require a positive mental well-being. Thus, investing in the mental health of the formerly incarcerated population decreases the risk of recidivism and bolsters community safety.

NIMH has an important role to play in supporting the mental health of people transitioning from jails and prisons. By researching and publishing findings on post-traumatic prison disorder, your agency will inform how Congress, state and local governments, and community-based organizations respond to the complex needs of people who experience incarceration.

For some, the trauma of incarceration isn't a bug so much as it is a feature. A lot of Americans like the idea of prisons being horrific places, because they have deeply absorbed the idea that this will scare people straight and deter them from committing crimes for fear of ending up there. This has not, by and large, been what has happened with our prison system. We know a lot of people go in and come out "worse" than they were previously — and while some of this could be chalked up to other prisoners being a bad influence and doling out crime tips, a lot of it is probably because going to prison is a traumatizing experience.

When some people go fishing, they just catch the fish, take a pose with it for the dating apps, and throw it back into the water thinking that it is the humane thing to do. That it's better to do this than to, say, take the fish home and eat it. Research shows, however, that having a giant hook pop through their lips is not only pretty upsetting for the fish, but that the hole in their lip makes it more difficult for them to suck up real, not-attached-to-a-fishing line food, making it harder for them to survive.

With incarceration, we are traumatizing people, on purpose, forcing them to become accustomed to that daily trauma and then sending them back into society with a big, giant hole in their lip like it's no big deal. And it's harder for them to survive as well. We know sending people into war frequently causes post-traumatic stress disorder and makes it difficult for those who come back to readjust to society. It's the same for prisoners.

The effects of trauma are not just that people feel badly or are upset. It can result in substance abuse, make it difficult to hold down a job, put strains on relationships with friends and family members, especially those who can never really understand what they went through. It happens whether or not they want it to, regardless of how tough or bootstrappy they are.

If we are going to put people in prison and send them back out again, we have to figure out how to heal them afterwards. By researching the effects of this trauma and finding out what would help, we're not just helping those people on a personal level, we are also helping ourselves as a society.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

Wonkette is independent and fully funded by readers like you. Click below to tip us!

I think that it would be easier to argue for prison if we had UBI. Some of the meanest people I know about prison are poor. They want those fucking thieves in jail, they are more at risk. Then when the thieves are in hail, they are angry that the thieves are getting "free food and health care". Yes the food is hideous and the health care highly questionable. I am reporting comments not agreeing with them.

So, anyway, I think it would be easier to argue for education, health care, and enough money for food in prison if we also had those things outside of prison.

I understand why the state has higher responsibilities to the people who are literally in state custody.

I think lack of UBI has so very many negative second order effects. This is one more.

Sexism is far more openly embraced.

"Biden, wearing a conservative suit designed by Dude Designer, and highlighted the look with a silk Garcia tie. Working to show strength yet remain friendly, he balanced smiling with no over-using his annoying voice."