Parents, Authors, Publisher Make Florida Book Censorship A Federal Case

What we need now is a drag queen named 'Sue Florida.'

Americans are getting pretty sick and tired of rightwing scolds trying to turn the country into a year-round Jesus Camp. Now the resistance to the last couple years of moral panics is spreading beyond the awesome kids forming banned book clubs and the civil rights groups suing to throw out unconstitutional laws. In Florida, Big Bidniss is throwing its money into the fight, too, as Judd Legum writes in his Popular Information newsletter.

In response to the Escambia County School Board's removals and restrictions on school library books, the board is being sued in federal court by some very big guns: publisher Penguin (heh) Random House, five authors, two parents of children in the school district, and the freedom to read nonprofit PEN America, alleging that the school board is violating the First Amendment rights of all the plaintiffs.

The lawsuit alleges that the school board banned and restricted books "based on their disagreement with the ideas expressed in those books." In so doing, the school board has "prescribed an orthodoxy of opinion that violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments."

“In Escambia County, state censors are spiriting books off shelves in a deliberate attempt to suppress diverse voices. In a nation built on free speech, this cannot stand,” Suzanne Nossel, the CEO of PEN America, said. “The law demands that the Escambia County School District put removed or restricted books back on library shelves where they belong.”

If "Escambia County" and "censorship" ring a bell, that would be because Escambia County is home to Moms for Liberty And Censorship activist Vicki Baggett, a high school English teacher and self-appointed Fahrenheit 451 fire crew who has filed over 150 book challenges.

Misty Book-Burning Memories

Why Is A Florida High School English Teacher Trying To Ban Books? Could It Be ... She's Racist?

Florida Censor Lady Should Know Better Than To Come At Betty White

Doodoo Process

Escambia County's actions are especially rotten, the suit alleges, because in many cases where Baggett challenged materials like the gay penguin book And Tango Makes Three, an official "materials review committee" — including a librarian, an elementary school teacher, a parent, a school administrator, and a community member — reviewed the materials and found they didn't violate the "Don't Say Gay" law because there's nothing remotely sexual in them.

But then Baggett would appeal to the school board, which routinely overrode the committee's decision and agreed that children needed to be "protected" from content she considered unfit for children. So far, the board has reversed the materials review committee's decisions and removed at least 10 books targeted by Baggett, with many more books still restricted while they're pending review. That includes the gay penguin book, which we should probably note is not a gay Penguin Random House book, although that would be funnier.

As the Washington Post 's Ben Sargent points out (gift link), the lawsuit cleverly doesn't target DeSantis's pet censorship laws and policies directly.

Instead, it argues that the removals themselves are unconstitutional. If the courts agree, this could create clearer prohibitions on school boards banning books for ideological reasons , regardless of what fig leaf rationale they cite.

The First Amendment: It's For Kids Too!

Multiple Supreme Court rulings, most notably 1983's Board of Education v. Pico decision, have held that school boards and administrators aren't allowed to remove books they don't like, especially not for "narrowly partisan or political" reasons. Students have a right to read, and just winning an election doesn't give anyone the right to impose ideological limits on what library books are available, as Legum 'splains:

Specifically, the court in Pico explained, "students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding." The court emphasized that the "school library is the principal locus of such freedom." The school library is the place where "a student can literally explore the unknown, and discover areas of interest and thought not covered by the prescribed curriculum."

The lawsuit contends Escambia County School Board members really stepped knee-deep in unconstitutional doody by ignoring "the expert judgment" of the school's own review committee, which found the books were educationally appropriate. The board rolled over that process and agreed with Baggett in every case, "despite the transparently ideological nature of her challenges." And that ain't allowed.

The lawsuit also argues that, by disproportionately removing books by people of color, by LGBTQ+ authors, or books on race or LGBTQ+ topics, the board was violating the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection clause. The complaint argues that the

"clear agenda behind the campaign to remove the books is to categorically remove all discussion of racial discrimination or LGBTQ issues from public school libraries." [...]

Further, the school board is "currently restricting access to virtually any book that … references the existence of same-sex relationships or transgender persons—without regard to anything else about the book’s contents."

Well sure, because just seeing the words "my dads" will turn kids gay, that's just science.

Pornographic My Ass

Beyond the 10 books banned at Baggett's behest, another 154 books in Escambia County schools are on "restricted" status while they move through the review process. The complaint — it's a pretty good read, because literate and literary lawyers — notes that the school board claimed it had no choice but to restrict books alleged to be "pornographic" or "harmful to minors" as defined by Florida law. But wait, is the school board claiming its own libraries contained more than 150 pornographic books?

Well yes, says the complaint, because they're ignoring the actual statute, which — unlike Baggett and the school board — pays attention to the damn First Amendment. The very narrow statutory language says a book is harmful only if it

“[p]redominately appealsto a prurient, shameful, or morbid interest,” and “[t]aken as a whole, iswithout serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors.”Fla. Stat., § 847.001(7)(a)-(c) (emphases added). None of the books at issue here qualify as harmful material under this standard.

In practice, the suit says, the district has been restricting any book that was "challenged on the ground that it contains 'sexual' content, regardless of the nature of that content or anything else about the book."

Using that excessively broad standard, the district restricted access to Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five (published by plaintiff Penguin Random House), because it allegedly contains "bestiality, nudity, [and] crude language." Yes, bestiality, since Billy Pilgrim's psychotic fellow soldier Roland Weary carries around a "print of the first dirty photograph in history," showing a woman attempting intercourse with a Shetland pony. The torture-obsessed Weary is clearly depicted as a creep, not a role model. Nonetheless, Vonnegut's masterpiece is restricted. So it goes.

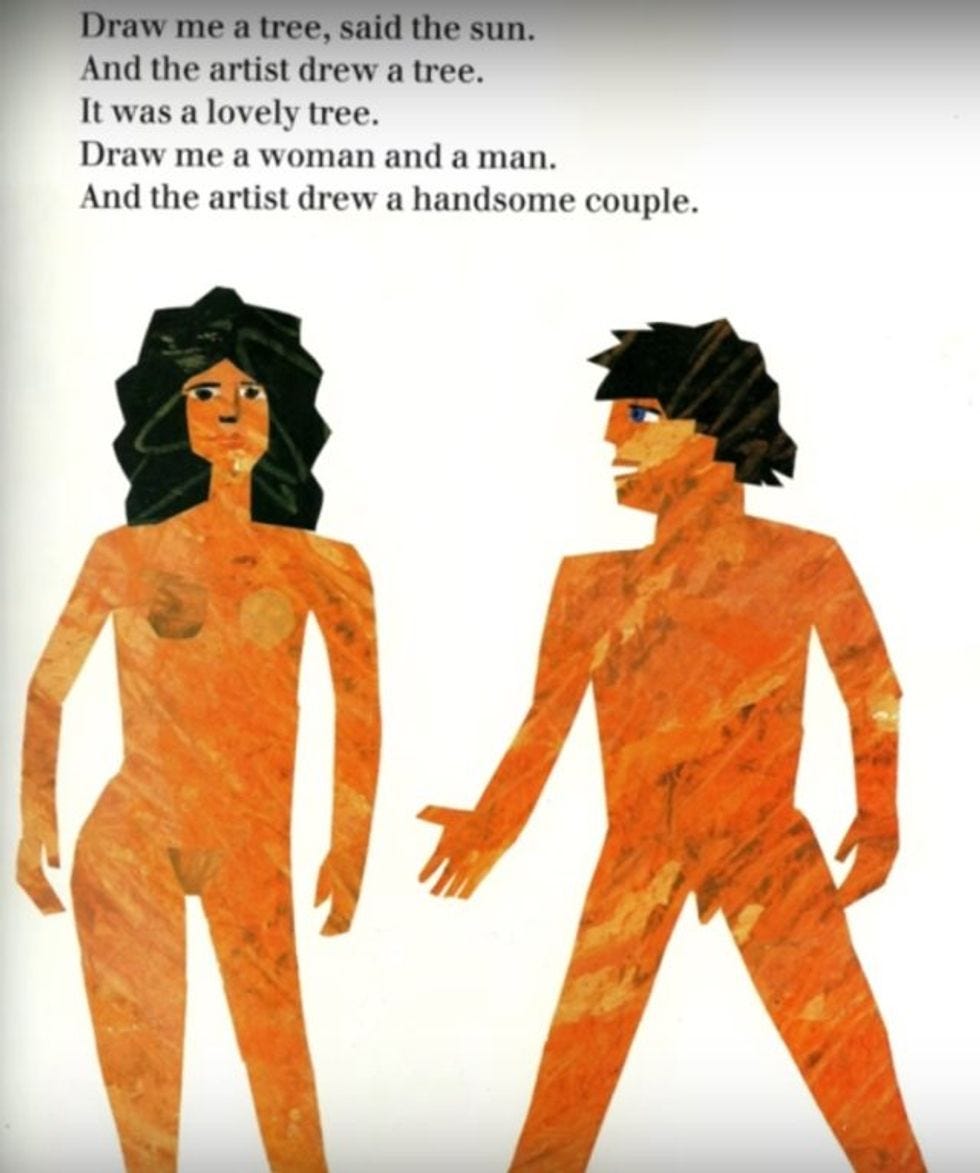

Similarly, Eric Carle's Draw Me a Star is restricted from elementary library shelves while it's being reviewed to determine if the author of The Very Hungry Caterpillar committed hardcore pornography. You tell us:

Maybe another seven months to determine whether it's porn.

The lawsuit adds that many books containing even the slightest reference to LGBTQ identity, like mention of a character's two dads, were challenged and remain on the restricted list for allegedly violating the "Don't Say Gay" law, even though it applies solely to "classroom materials" not library books.

Just having a restricted list at all is also a First Amendment violation, the complaint argues:

The barriers for students to access restricted books are significant. To access them, a student—who could be as young as 5 years old—must find a librarian, ask the librarian for permission to access a book that has been designated as “pornographic” or otherwise unsuitable for school-aged children, and then wait while that librarian verifies that the student, in fact, has parental permission to access it. Forcing students to undertake these steps, and endure the stigma that goes along with undertaking them, is having a profound chilling effect on students seeking access to the restricted books

And since the "review" period can take up an entire school year, the suit argues, the board is essentially allowing any private citizen with an agenda to indefinitely restrict books for all families in the district, and there you go again, violating the First Amendment.

At some point, as we see similar lawsuits and resistance by parents who don't want to live under the thumb of self-appointed moral guardians, this nonsense is going down to defeat. The sooner the better.

[ Popular Information / WaPo (gift link) / Photoshoop image by Wonkette,Background image by Eli Duke, Creative Commons License 2.0. Note: And Tango Makes Three is published by Little Simon, not by Penguin Random House.]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please give $5 or $10 a month so we can keep you on top of the news, which turns out not to be pornographic after all — although censorship is obscene.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

Vicki Biggott , IMHO, should not have the responsibility of being a teacher, since she is mentally and emotionally unstable. Of course FL can’t replace her easily, because teachers are so poorly paid. I feel bad for her students.

And I'm basically assumed to not have genitalia, because wheelchair. It's just science.