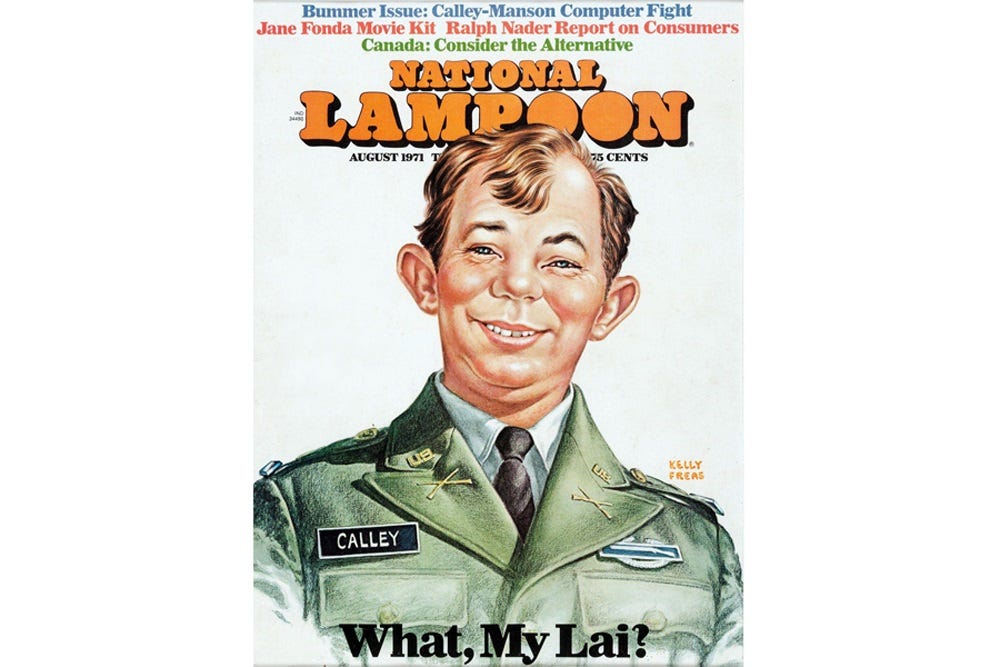

William Calley Dead At 80 Before Trump Could Appoint Him Head Of Army

The real shame? Hugh Thompson, who stopped the massacre, has nothing like the same name recognition.

Former US Army Lt. William Calley, who was the only person prosecuted for the 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam, died April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Florida. Unlike the 374 men, women, and children the Army said were murdered — mostly shot at point blank range while lined up in ditches — at My Lai and Son Mai on March 16, 1968 (Vietnam places the death toll at 504), Calley passed away under medical care at the end of a long life.

Like the massacre that will always be attached to his name, news of Calley’s death took some time to be revealed; the Washington Post reports (gift link) it was

alerted to the death, which was not previously reported, by Zachary Woodward, a recent Harvard Law School graduate who said he noticed Mr. Calley’s death while looking through public records.

The Post says that Calley’s death certificate, from the Florida Department of Health in Alachua County,

matched known details about his life — including information on his birth, career, name and nickname — but featured one notable omission. On a line asking if he had ever served “in U.S. armed forces,” the answer given was “no.”

So that’s either a hell of a clerical error or the final act of a war criminal who knew exactly what he’d done; the obit notes Calley’s 2009 public “apology” in a speech to a Kiwanis Club meeting in Columbus, Ohio, perhaps the blandest possible forum for an infamous mass murderer to express regret for his actions.

“There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai,” he said. “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

During the speech, he also said that he had just been following orders, a declaration that irritated critics who questioned whether he had experienced a change of heart.

Both sides, yes. Calley was convicted at court-martial of murdering 22 unarmed civilians and sentenced to life in prison at hard labor, but President Nixon ordered him placed under house arrest instead; as his appeals dragged forward, he ultimately served about three years before being released. The Post notes that later in life he took an umbrella with him whenever he went out, to hide from photographers.

The Source Of All Knowledge reminds us that many Americans were outraged by the life sentence, and that then-governor of Georgia Jimmy Carter responded by instituting “American Fighting Man's Day, and asked Georgians to drive for a week with their lights on.” Also this:

Nixon received so many telegrams from Americans requesting clemency or a pardon for William Calley that he remarked to Henry Kissinger, “Most people don't give a shit whether he killed them or not.”

And yes, of course the responsibility for My Lai went far beyond Calley, to include Capt. Ernest Medina, who sent Calley and his Charlie Company (and another unit, Bravo Company) to the village with orders to wipe out anything that was “walking, crawling or growling,” and reassuring them that any innocent civilians were at a market. Everyone in the village was by definition a guerrilla or a supporter.

“They’re all VC, now go and get them,” he said, according to trial testimony.

The Post interviewed war correspondent Thomas Ricks, a former Post reporter who wrote the essential Iraq War book Fiasco and the more recent The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today. Ricks called My Lai “the absolute low point in the history of the modern U.S. military,” and explained the impact it eventually had on US military leadership — over time, at least:

Beyond the atrocities committed by Mr. Calley, Ricks said it was important to remember that “there were 1,000 causes here, bad people doing bad things up and down the chain of command,” including the “second grave sin” of the coverup.

“My Lai forced a reexamination of the U.S. Army,” Ricks noted, referring to its central role in later studies about revamping military professionalism. “It was not just that hundreds of civilians had been murdered, and a score raped, but that the acts of the day were covered up by the Army chain of command.

“The incident was just not the work of a deranged lieutenant,” he continued. “Other officers were aware of what was going on. And the extensive coverup, including the destruction of documents, went all the way up to the rank of general, with two generals and three colonels implicated.”

One indication that at least some parts of the military learned something from My Lai is that in 1998, however belatedly, the Army awarded the Soldier’s Medal to Hugh Thompson, a warrant officer flying an observation helicopter, who effectively put an end to the massacre. Thompson sent the positions of wounded Vietnamese civilians on the ground to call for them to get medical treatment, but subsequently saw they had been shot. Then he witnessed a soldier killing a wounded woman. As PBS explains,

Shocked by this illegal behavior, Thompson came across another group of civilians guarded by a soldier. In an unprecedented and unauthorized move, he landed his helicopter and appealed to a soldier to help the civilians. The soldier responded that he was "putting them out of their misery," and shot the group down moments after Thompson's departure. Landing his helicopter a second time, Thompson ordered Andreotta and Colburn to train their guns on the members of Charlie Company who were in pursuit a group of 12 to 15 Vietnamese women, children, and elderly men. Calling in assistance from other nearby choppers, Thompson and his men brought the group to safety four miles away.

Thompson filed an action report calling attention to the war crimes, and for his efforts he was rewarded with increasingly dangerous assignments, leading him to be shot down four times; on a fifth mission, his helicopter shot down again, crashing so violently that his back was broken. “[He] narrowly escaped death from nearby Vietcong. In April, Thompson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions at My Lai, a document he threw away.”

It was only decades later that Thompson began to receive recognition for his own heroism in intervening at My Lai. At the time, though, he was seen as a troublemaker, even a traitor, for ratting out Calley and undermining his superiors. Thompson died in 2006.

For Americans who supported the war, and The Troops, Calley was a sort of underdog hero, a guy who was just exacting justified revenge (on innocent civilians, but they didn’t matter) on the communists who had been killing his men. Anyone killed by America, after all, is a bad guy.

That’s pretty much the thinking embodied by Donald Trump, who marked Memorial Day 2019 by pardoning US military personnel accused and even convicted of war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. After all, Fox News was calling the American war crimers “heroes” too, so whatever they did was justified and patriotic. It was, as we noted at the time, the second time he pardoned US military war criminals, because we’re the best nation, and nothing our troops do can ever be wrong. Now Trump wants to get back in the Oval Office, with a fresh Supreme Court ruling that he too can never be held criminally responsible for what he does in office.

Also, somewhere in here we should mention what a goddamned shame it is that Sy Hersh, who brought the My Lai atrocities to public notice and won the 1970 Pulitzer for it, has since become a conspiracy-chasing wackaloon himself.

No word on whether Trump intends to campaign on a promise to posthumously award Calley the Presidential Medal of Freedom, or to order the Pentagon to give him a Medal of Honor. If he gets back in office, he can do what he wants, because America.

[WaPo (gift link) / American Experience PBS /

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please become a paid subscriber, or if you prefer a one-time donation, it’s freedom, man.

Shameful, shameful, shameful. And what's more, sociopaths like Trump and his buddies would be perfectly comfortable emboldening the American military apparatus to commit further atrocities just like it. Yet another reason we cannot dishonor the office of President with his stain.

I think about Hugh Thompson a lot, actually. I've thought for years about the courage it took to stand up in the middle of madness and say "not one step further." It's a bravery that I can't really comprehend.